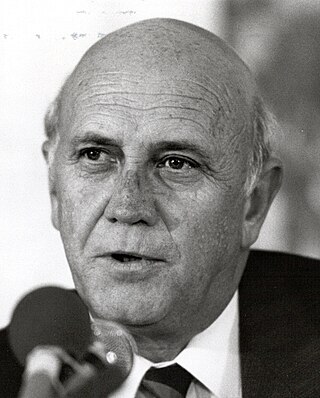

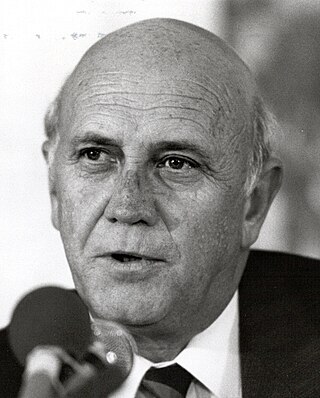

Frederik Willem de Klerk was a South African politician who served as state president of South Africa from 1989 to 1994 and as deputy president from 1994 to 1996. As South Africa's last head of state from the era of white-minority rule, he and his government dismantled the apartheid system and introduced universal suffrage. Ideologically a social conservative and an economic liberal, he led the National Party (NP) from 1989 to 1997.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was a court-like restorative justice body assembled in South Africa in 1996 after the end of apartheid. Authorised by Nelson Mandela and chaired by Desmond Tutu, the commission invited witnesses who were identified as victims of gross human rights violations to give statements about their experiences, and selected some for public hearings. Perpetrators of violence could also give testimony and request amnesty from both civil and criminal prosecution.

Repentance is reviewing one's actions and feeling contrition or regret for past wrongs, which is accompanied by commitment to and actual actions that show and prove a change for the better.

Miroslav Volf is a Croatian Protestant theologian and public intellectual and Henry B. Wright Professor of Theology and director of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture at Yale University. He previously taught at the Evangelical Theological Seminary in his native Osijek, Croatia and Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California (1990–1998).

Country of My Skull is a 1998 nonfiction book by Antjie Krog about the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). It is based on Krog's experience as a radio reporter, covering the Commission from 1996 to 1998 for the South African Broadcasting Corporation. The book explores the successes and failures of the Commission, the effects of the proceedings on her personally, and the possibility of genuine reconciliation in post-Apartheid South Africa.

Alan Michael Lapsley, SSM is a South African Anglican priest and social justice activist.

A truth commission, also known as a truth and reconciliation commission or truth and justice commission, is an official body tasked with discovering and revealing past wrongdoing by a government, in the hope of resolving conflict left over from the past. Truth commissions are, under various names, occasionally set up by states emerging from periods of internal unrest, civil war, or dictatorship marked by human rights abuses. In both their truth-seeking and reconciling functions, truth commissions have political implications: they "constantly make choices when they define such basic objectives as truth, reconciliation, justice, memory, reparation, and recognition, and decide how these objectives should be met and whose needs should be served".

In My Country is a 2004 drama film directed by John Boorman, and starring Samuel L. Jackson and Juliette Binoche. It is centred around the story of Afrikaner poet Anna Malan (Binoche) and an American journalist, Langston Whitfield (Jackson), sent to South Africa to report about the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings.

The Kairos Document (KD) is a theological statement issued in 1985 by a group of mainly black South African theologians based predominantly in the townships of Soweto, South Africa. The document challenged the churches' response to what the authors saw as the vicious policies of the apartheid regime under the state of emergency declared on 21 July 1985. The KD evoked strong reactions and furious debates not only in South Africa, but world-wide.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. He was Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then Archbishop of Cape Town from 1986 to 1996, in both cases being the first black African to hold the position. Theologically, he sought to fuse ideas from black theology with African theology.

The Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) is a Parliament-enacted organization created in May 2005 under the Transitional Government. The Commission worked throughout the first mandate of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf after she was election President of Liberia in November 2005. The Liberian TRC came to a conclusion in 2010, filing a final report and recommending relevant actions by national authorities to ensure responsibility and reparations.

The Elders is an international non-governmental organisation of public figures noted as senior statesmen, peace activists and human rights advocates, who were brought together by Nelson Mandela in 2007. They describe themselves as "independent global leaders working together for peace, justice, human rights and a sustainable planet". The goal Mandela set for The Elders was to use their "almost 1,000 years of collective experience" to work on solutions for seemingly insurmountable problems such as climate change, HIV/AIDS, and poverty, as well as to "use their political independence to help resolve some of the world's most intractable conflicts".

Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela is the Research Chair in Studies in Historical Trauma and Transformation at Stellenbosch University in South Africa. She graduated from Fort Hare University with a bachelor's degree and an Honours degree in psychology. She obtained her master's degree in Clinical Psychology at Rhodes University. She received her PhD in psychology from the University of Cape Town. Her doctoral thesis, entitled "Legacies of violence: An in-depth analysis of two case studies based on interviews with perpetrators of a 'necklace' murder and with Eugene de Kock", offers a perspective that integrates psychoanalytic and social psychological concepts to understand extreme forms of violence committed during the apartheid era. Her main interests are traumatic memories in the aftermath of political conflict, post-conflict reconciliation, empathy, forgiveness, psychoanalysis and intersubjectivity. She served on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). She currently works at the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein as a senior research professor.

A Human Being Died That Night is a 2003 book by Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela.

The Solomon Islands Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) is a commission officially established by the government of Solomon Islands in September 2008. It has been formed to investigate the causes of the ethnic violence that gripped Solomon Islands between 1997 and 2003. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission is the first of its kind in the Pacific Islands region.

Alexander Lionel Boraine was a South African politician, minister, and anti-apartheid activist.

The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) is a non-governmental organisation and think tank based in Cape Town, South Africa. It was forged out of the country's Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2000. The aim was to ensure that lessons learnt from South Africa's transition from apartheid to democracy were taken into account as the nation moved ahead. Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu was the patron of the IJR.

John W. de Gruchy is a Christian theologian known for his work resisting apartheid. He is presently Emeritus Professor at the University of Cape Town and Extraordinary Professor at the University of Stellenbosch.

Ubuntu theology is a Southern African Christian perception of the African Ubuntu philosophy that recognizes the humanity of a person through a person's relationship with other persons. It is best known through the writings of the Anglican archbishop Desmond Tutu, who, drawing from his Christian faith, theologized Ubuntu by a model of forgiveness in which human dignity and identity are drawn from the image of the triune God. Human beings are called to be persons because they are created in the image of God.

Reconciliation theology in Northern Ireland is a contextual process and a divine goal which involves working to create freedom and peace in Northern Ireland. As with reconciliation theology more widely, reconciliation theology in Northern Ireland emphasises the concepts of truth, justice, forgiveness, and repentance. A theology of reconciliation is practically applied by reconciliation communities.