Related Research Articles

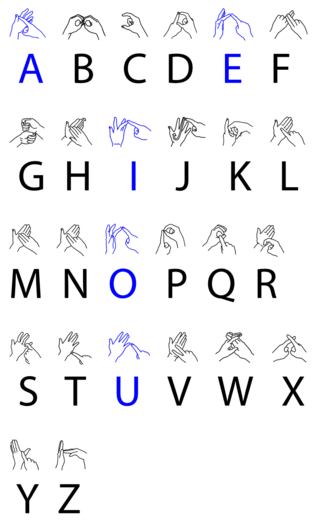

British Sign Language (BSL) is a sign language used in the United Kingdom and is the first or preferred language among the deaf community in the UK. While private correspondence from William Stokoe hinted at a formal name for the language in 1960, the first usage of the term "British Sign Language" in an academic publication was likely by Aaron Cicourel. Based on the percentage of people who reported 'using British Sign Language at home' on the 2011 Scottish Census, the British Deaf Association estimates there are 151,000 BSL users in the UK, of whom 87,000 are Deaf. By contrast, in the 2011 England and Wales Census 15,000 people living in England and Wales reported themselves using BSL as their main language. People who are not deaf may also use BSL, as hearing relatives of deaf people, sign language interpreters or as a result of other contact with the British Deaf community. The language makes use of space and involves movement of the hands, body, face and head.

Interpreting is a translational activity in which one produces a first and final target-language output on the basis of a one-time exposure to an expression in a source language.

New Zealand Sign Language or NZSL is the main language of the deaf community in New Zealand. It became an official language of New Zealand in April 2006 under the New Zealand Sign Language Act 2006. The purpose of the act was to create rights and obligations in the use of NZSL throughout the legal system and to ensure that the Deaf community had the same access to government information and services as everybody else. According to the 2013 Census, over 20,000 New Zealanders know NZSL.

The National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters Ltd is the national standards and certifying body for translators and interpreters in Australia. NAATI's mission, as outlined in the NAATI Constitution, is to set and maintain high national standards in translating and interpreting to enable the existence of a pool of accredited translators and interpreters responsive to the changing needs and demography of the Australian community. The core focus of the company is issuing certification for practitioners who wish to work as translators and interpreters in Australia.

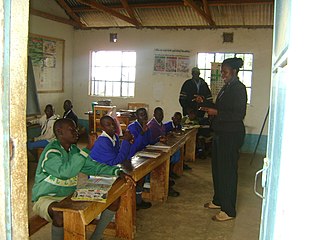

Kenyan Sign Language is a sign language used by the deaf community in Kenya and Somalia. It is used by over half of Kenya's estimated 600,000 deaf population. There are some dialect differences between Kisumu, Mombasa and Somalia.

The National Association of the Deaf (NAD) is an organization for the promotion of the rights of deaf people in the United States. NAD was founded in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1880 as a non-profit organization run by Deaf people to advocate for deaf rights, its first president being Robert P. McGregor of Ohio. It includes associations from all 50 states and Washington, DC, and is the US member of the World Federation of the Deaf, which has over 120 national associations of Deaf people as members. It has its headquarters in Silver Spring, Maryland.

A video relay service (VRS), also sometimes known as a video interpreting service (VIS), is a video telecommunication service that allows deaf, hard-of-hearing, and speech-impaired (D-HOH-SI) individuals to communicate over video telephones and similar technologies with hearing people in real-time, via a sign language interpreter.

The Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, also known as AG Bell, is an organization that aims to promote listening and spoken language among people who are deaf and hard of hearing. It is headquartered in Washington, D.C., with chapters located throughout the United States and a network of international affiliates.

Video remote interpreting (VRI) is a videotelecommunication service that uses devices such as web cameras or videophones to provide sign language or spoken language interpreting services. This is done through a remote or offsite interpreter, in order to communicate with persons with whom there is a communication barrier. It is similar to a slightly different technology called video relay service, where the parties are each located in different places. VRI is a type of telecommunications relay service (TRS) that is not regulated by the FCC.

The Florida Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (FRID) is a non-profit organization aimed at helping interpreters for the deaf and hard of hearing living within the state of Florida. FRID is a state affiliate of the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. FRID has over 950 members as of 2009.

Deaf education is the education of students with any degree of hearing loss or deafness. This may involve, but does not always, individually-planned, systematically-monitored teaching methods, adaptive materials, accessible settings, and other interventions designed to help students achieve a higher level of self-sufficiency and success in the school and community than they would achieve with a typical classroom education. There are different language modalities used in educational setting where students get varied communication methods. A number of countries focus on training teachers to teach deaf students with a variety of approaches and have organizations to aid deaf students.

Signature is a United Kingdom national charity and awarding body for deaf communication qualifications. Signature attempts to improve communication between deaf, deafblind and hearing people, whilst creating better communities.

HASA is a social benefit 501(c)(3) organization located in Baltimore, Maryland, that specializes in facilitating communication. Established in 1926, the organization provides special education services through Gateway School, audiology and speech-language services through its Clinical Services Department, and interpreting services for the deaf through its CIRS Interpreting Department.

Language deprivation in deaf and hard-of-hearing children is a delay in language development that occurs when sufficient exposure to language, spoken or signed, is not provided in the first few years of a deaf or hard of hearing child's life, often called the critical or sensitive period. Early intervention, parental involvement, and other resources all work to prevent language deprivation. Children who experience limited access to language—spoken or signed—may not develop the necessary skills to successfully assimilate into the academic learning environment. There are various educational approaches for teaching deaf and hard of hearing individuals. Decisions about language instruction is dependent upon a number of factors including extent of hearing loss, availability of programs, and family dynamics.

ASL interpreting is the real-time translation between American Sign Language (ASL) and another language to allow communication between parties who do not share functional use of either language. Domains of practice include medical/mental health, legal, educational/vocational training, worship, and business settings. Interpretation may be performed consecutively, simultaneously or a combination of the two, by an individual, pair, or team of interpreters who employ various interpreting strategies. ASL interpretation has been overseen by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf since 1964.

Deaf mental health care is the providing of counseling, therapy, and other psychiatric services to people who are deaf and hard of hearing in ways that are culturally aware and linguistically accessible. This term also covers research, training, and services in ways that improve mental health for deaf people. These services consider those with a variety of hearing levels and experiences with deafness focusing on their psychological well-being. The National Association of the Deaf has identified that specialized services and knowledge of the Deaf increases successful mental health services to this population. States such as North Carolina, South Carolina, and Alabama have specialized Deaf mental health services. The Alabama Department of Mental Health has established an office of Deaf services to serve the more than 39,000 deaf and hard of hearing person who will require mental health services.

Sanjay Gulati is a child psychiatrist in Massachusetts whose research revolves around people who are deaf and hard of hearing and whose focus is on educating professionals working with deaf and hard of hearing populations about language deprivation syndrome. He is credited with coining the concept of language deprivation syndrome and studies the constellation of behaviors that result from lacking a foundational first language in deaf children.

Marla Berkowitz is an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter. Berkowitz is the only ASL Certified Deaf Interpreter in the US state of Ohio. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, she became known because of her interpretation of Ohio governor Mike DeWine's daily press conferences.

Deafness in Portugal involves several elements such as the history, education, community, and medical treatment that must be understood to grasp the experiences of deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) individuals in this region. Currently there are 60,000 people in Portugal that are deaf sign language users. Among that number are 100 working sign language interpreters. Currently, the form of sign language used in Portugal is Portuguese Sign Language. In Portugal, the cities Lisbon and Porto have the largest deaf populations.

In Ireland, 8% of adults are affected by deafness or severe hearing loss. In other words, 300,000 Irish require supports due to their hearing loss.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fant, Louie J. (1990). Silver threads : a personal look at the first twenty-five years of the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Inc Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Silver Spring, Md., USA: RID Publications. ISBN 0-916883-08-6. OCLC 22708289.

- ↑ janelleb. "Maintaining Certification". Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ↑ admin. "Ethics Overview". Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ↑ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-30. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ↑ "Disability Legislation History". Student Disability Center. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- 1 2 3 Ball, Carolyn (2013). Legacies and legends : history of interpreter education from 1800 to the 21st century. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. ISBN 978-0-9697792-8-5. OCLC 854936643.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Babbidge, Homer D.; Others, And (1965). EDUCATION OF THE DEAF. A REPORT TO THE SECRETARY OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE BY HIS ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE EDUCATION OF THE DEAF.

- ↑ Adler, Edna P., ed. (1969). Deafness: Research and Professional Training Programs on Deafness Sponsored by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

- 1 2 Signed language interpreting in the 21st century : an overview of the profession. Len Roberson, Sherry Shaw. Washington, DC. 2018. ISBN 978-1-944838-25-6. OCLC 1048896222.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ admin. "RID Board of Directors". Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- 1 2 admin. "HQ Staff". Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- 1 2 3 "NAD-RID Code of Professional Conduct" (PDF). Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ "About RID Overview". Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ "Exam Request Form". form.jotform.com. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ↑ Furman, Sean. "Center for the Assessment of Sign Language Interpretation". Center for Assessment of Sign Language Interpreters. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- ↑ helloadmin. "About CASLI". Center for Assessment of Sign Language Interpreters. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ↑ "Standards and Criteria Feb 2016.pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ↑ admin. "Ethics Overview". Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ↑ "EPS Policy Manual Working Document Public". Google Docs. Retrieved 2022-07-25.