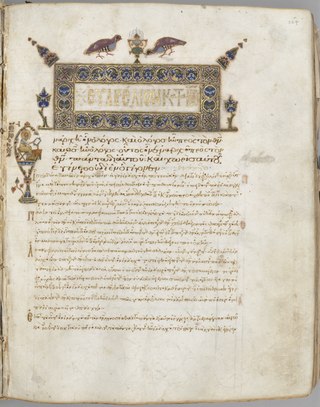

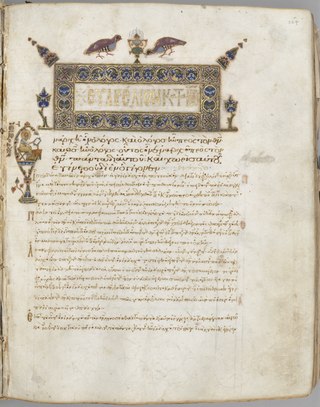

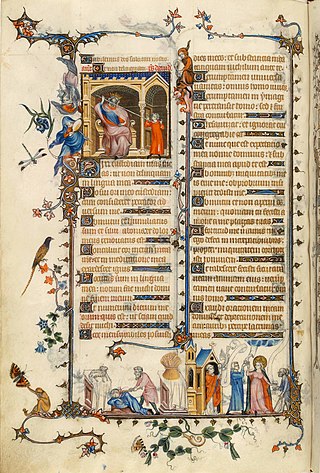

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is decorated with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers and liturgical books such as psalters and courtly literature, the practice continued into secular texts from the 13th century onward and typically include proclamations, enrolled bills, laws, charters, inventories, and deeds.

JeanFouquet was a French painter and miniaturist. A master of panel painting and manuscript illumination, and the apparent inventor of the portrait miniature, he is considered one of the most important painters from the period between the late Gothic and early Renaissance. He was the first French artist to travel to Italy and experience first-hand the early Italian Renaissance.

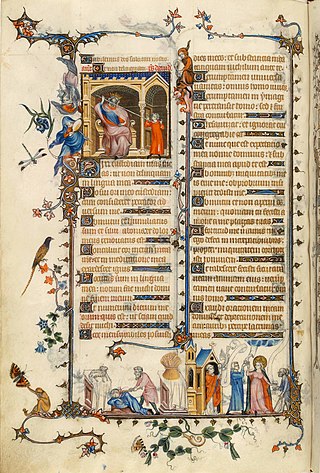

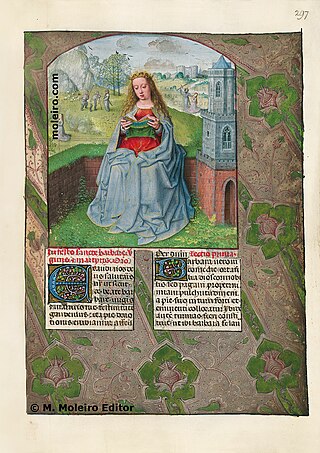

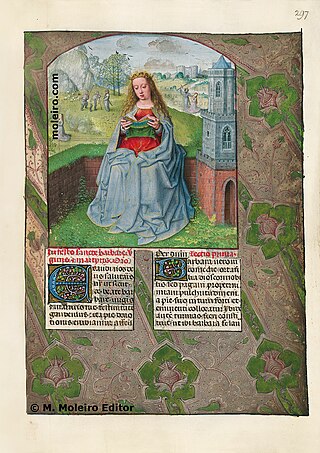

Books of hours are Christian prayer books, which were used to pray the canonical hours. The use of a book of hours was especially popular in the Middle Ages, and as a result, they are the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Like every manuscript, each manuscript book of hours is unique in one way or another, but most contain a similar collection of texts, prayers and psalms, often with appropriate decorations, for Christian devotion. Illumination or decoration is minimal in many examples, often restricted to decorated capital letters at the start of psalms and other prayers, but books made for wealthy patrons may be extremely lavish, with full-page miniatures. These illustrations would combine picturesque scenes of country life with sacred images.

A miniature is a small illustration used to decorate an ancient or medieval illuminated manuscript; the simple illustrations of the early codices having been miniated or delineated with that pigment. The generally small scale of such medieval pictures has led to etymological confusion with minuteness and to its application to small paintings, especially portrait miniatures, which did however grow from the same tradition and at least initially used similar techniques.

Jean Pucelle was a Parisian Gothic-era manuscript illuminator who excelled in the invention of drolleries as well as traditional iconography. He is considered one of the best miniaturists of the early 14th century. He worked primarily under the patronage of the royal court and is believed to have been responsible for the introduction of the arte nuovo of Giotto and Duccio to Northern Gothic art. His work shows a distinct influence of the Italian trecento art Duccio is credited with creating. His style is characterized by delicate figures rendered in grisaille, accented with touches of color.

Simon Marmion was a French and Burgundian Early Netherlandish painter of panels and illuminated manuscripts. Marmion lived and worked in what is now France but for most of his lifetime was part of the Duchy of Burgundy in the Southern Netherlands.

The Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux is an illuminated book of hours in the Gothic style. According to the usual account, it was created between 1324 and 1328 by Jean Pucelle for Jeanne d'Evreux, the third wife of Charles IV of France. It was sold in 1954 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York where it is now part of the collection held at The Cloisters, and usually on display.

Lucas Horenbout, often called Hornebolte in England, was a Flemish artist who moved to England in the mid-1520s and worked there as "King's Painter" and court miniaturist to King Henry VIII from 1525 until his death. He was trained in the final phase of Netherlandish illuminated manuscript painting, in which his father Gerard was an important figure, and was the founding painter of the long and distinct English tradition of portrait miniature painting. He has been suggested as the Master of the Cast Shadow Workshop, who produced royal portraits on panel in the 1520s or 1530s.

The Master of James IV of Scotland was a Flemish manuscript illuminator and painter most likely based in Ghent, or perhaps Bruges. Circumstantial evidence, including several larger panel paintings, indicates that he may be identical with Gerard Horenbout. He was the leading illuminator of the penultimate generation of Flemish illuminators. The painter's name is derived from a portrait of James IV of Scotland which, together with one of his Queen Margaret Tudor, is in the Prayer book of James IV and Queen Margaret, a book of hours commissioned by James and now in Vienna. He has been called one of the finest illuminators active in Flanders around 1500, and contributed to many lavish and important books besides directing an active studio of his own.

The Rothschild Prayerbook or Rothschild Hours, is an important Flemish illuminated manuscript book of hours, compiled c. 1500–1520 by a number of artists.

The Isabella Breviary is a late 15th-century illuminated manuscript housed in the British Library, London. Queen Isabella I of Castile was given the manuscript shortly before 1497 by her ambassador Francisco de Rojas to commemorate the double marriage of her children and the children of Emperor Maximilian of Austria and Duchess Mary of Burgundy.

Taddeo Crivelli, also known as Taddeo da Ferrara, was an Italian painter of illuminated manuscripts. He is considered one of the foremost 15th-century illuminators of the Ferrara school, and also has the distinction of being the probable engraver of the first book illustrated with maps, which was also the first book using engraving.

The Ghent–Bruges school is a distinctive style of manuscript illumination which was prevalent in the Southern Netherlands from about 1475 to about 1550. Though the name highlights the importance of Ghent and Bruges as centres for manuscript production, manuscripts in the style were produced in a wider area.

The Pseudo-Jacquemart was an anonymous master illuminator active in Paris and Bourges between 1380 and 1415. He owed his name to his close collaboration with painter Jacquemart de Hesdin.

Étienne Colaud (also Étienne Collault was a French illuminator and book dealer, active in Paris between 1512 and 1540. A number of surviving archives indicate that he was based on the Île de la Cité, close to the cathedral of Notre-Dame, and that other family members also worked in the book trade. His clientele came from leading families of the time, including great land owners, top prelates, and even the king himself. Using a Book of hours that carries his name, scholars have attributed approximately twenty manuscripts to him by analysing the techniques and style applied. There are also a number of religious books, translations into French from Latin or Italian, chivalric narratives and illuminated texts. Étienne Colaud's style is strongly influenced by his near contemporary, the Parisian illuminator Jean Pichore, but his work indicates that he was also networked with virtually every other Paris book-artist of the period.

The Master of the Brussels Initials, previously identified with Zebo da Firenze, was a manuscript illuminator active mainly in Paris. He brought Italian influences to French manuscript illumination and in that way played an important role in the development of the so-called International Gothic style. Decorations by the artist appear in several different works, illustrated by several different artists, and some attributions have been questioned. A corpus of works attributable to the Master of the Brussels Initials was initially identified by art historians Otto Pächt and Millard Meiss. The artist's style was inventive, bright and lively, and G. Evelyn Hutchinson has also pointed out the unusually realistic depictions of minute wildlife found in his work. At one point the bibliophile John, Duke of Berry employed the Master of the Brussels Initials.

The Master of the Burgundian Prelates was an anonymous master illuminator active in Burgundy between 1470 and 1490. He owes his name to several works commissioned from him by Burgundian bishops and abbots.

The Missal of Thomas James is an illuminated manuscript produced around 1483 for Thomas James, Bishop of Dol in Brittany. It represents the text of a missal for use in Rome and was commissioned by the Breton prelate, who was close to Pope Sixtus IV and Italian humanist circles while living in the papal city. The work was produced by the Italian painter Attavante degli Attavanti and the people of his studio in Florence. It contains two full-page miniatures, two-thirds-page miniatures, 165 historiated initials, and numerous margins decorated with medallions depicting saints or scenes from the life of Christ. These decorations are representative of Florentine Renaissance art, inspired by ancient objects and Flemish art. It served as a model for other manuscripts by the same painter, including The Missal of Matthias Corvin. The manuscript remained in Dol-de-Bretagne until the 19th century when it was sold and acquired by an archbishop of Lyon. It is currently kept in the Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon under the reference Ms.5123. However, it has been partially mutilated: the frontispiece has been cut out and five sheets have been removed. One of them, depicting the Crucifixion, is kept in the Museum of Modern Art André Malraux in Le Havre.

The Bible of Federico da Montefeltro or Bibbia Urbinate is an illuminated manuscript containing the Vulgate text. It was commissioned by Federico III da Montefeltro and produced in Florence between 1476 and 1478. Now, it is housed in the Vatican Apostolic Library.

Gothic book illustration, or gothic illumination, originated in France and England around 1160/70, while Romanesque forms remained dominant in Germany until around 1300. Throughout the Gothic period, France remained the leading artistic nation, influencing the stylistic developments in book illustration. During the transition from the late Gothic period to the Renaissance, book illustration lost its status as one of the most important artistic genres in the second half of the 15th century, due to the widespread adoption of printing.