Related Research Articles

Physical education, often abbreviated to Phys. Ed. or PE, is a subject taught in schools around the world. PE is taught during primary and secondary education and encourages psychomotor, cognitive, and affective learning through physical activity and movement exploration to promote health and physical fitness. When taught correctly and in a positive manner, children and teens can receive a storm of health benefits. These include reduced metabolic disease risk, improved cardiorespiratory fitness, and better mental health. In addition, PE classes can produce positive effects on students' behavior and academic performance. Research has shown that there is a positive correlation between brain development and exercising. Researchers in 2007 found a profound gain in English Arts standardized test scores among students who had 56 hours of physical education in a year, compared to those who had 28 hours of physical education a year.

Media literacy is an expanded conceptualization of literacy that includes the ability to access and analyze media messages as well as create, reflect and take action, using the power of information and communication to make a difference in the world. Media literacy is not restricted to one medium and is understood as a set of competencies that are essential for work, life, and citizenship. Media literacy education is the process used to advance media literacy competencies, and it is intended to promote awareness of media influence and create an active stance towards both consuming and creating media. Media literacy education is part of the curriculum in the United States and some European Union countries, and an interdisciplinary global community of media scholars and educators engages in knowledge and scholarly and professional journals and national membership associations.

The Association of College and Research Libraries defines information literacy as a "set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning". In the United Kingdom, the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals' definition also makes reference to knowing both "when" and "why" information is needed.

Blended learning or hybrid learning, also known as technology-mediated instruction, web-enhanced instruction, or mixed-mode instruction, is an approach to education that combines online educational materials and opportunities for interaction online with physical place-based classroom methods.

Information and communications technology (ICT) is an extensional term for information technology (IT) that stresses the role of unified communications and the integration of telecommunications and computers, as well as necessary enterprise software, middleware, storage and audiovisual, that enable users to access, store, transmit, understand and manipulate information.

M-learning, or mobile learning, is a form of distance education where learners use portable devices such as mobile phones to learn anywhere and anytime. The portability that mobile devices provide allows for learning anywhere, hence the term "mobile" in "mobile learning." M-learning devices include computers, MP3 players, mobile phones, and tablets. M-learning can be an important part of informal learning.

Visual literacy is the ability to interpret, negotiate, and make meaning from information presented in the form of an image, extending the meaning of literacy, which commonly signifies interpretation of a written or printed text. Visual literacy is based on the idea that pictures can be "read" and that meaning can be discovered through a process of reading.

Employability refers to the attributes of a person that make that person able to gain and maintain employment.

Children's culture includes children's cultural artifacts, children's media and literature, and the myths and discourses spun around the notion of childhood. Children's culture has been studied within academia in cultural studies, media studies, and literature departments. The interdisciplinary focus of childhood studies could also be considered in the paradigm of social theory concerning the study of children's culture.

Idit R. Harel is an Israeli-American entrepreneur and CEO of Globaloria. She is a learning sciences researcher and pioneer of Constructionist learning-based EdTech interventions.

Technological literacy is the ability to use, manage, understand, and assess technology. Technological literacy is related to digital literacy in that when an individual is proficient in using computers and other digital devices to access the Internet, digital literacy gives them the ability to use the Internet to discover, review, evaluate, create, and use information via various digital platforms, such as web browsers, databases, online journals, magazines, newspapers, blogs, and social media sites.

Digital literacy is an individual's ability to find, evaluate, and communicate information using typing or digital media platforms. It is a combination of both technical and cognitive abilities in using information and communication technologies to create, evaluate, and share information.

An edublog is a blog created for educational purposes. Edublogs archive and support student and teacher learning by facilitating reflection, questioning by self and others, collaboration and by providing contexts for engaging in higher-order thinking. Edublogs proliferated when blogging architecture became more simplified and teachers perceived the instructional potential of blogs as an online resource. The use of blogs has become popular in education institutions including public schools and colleges. Blogs can be useful tools for sharing information and tips among co-workers, providing information for students, or keeping in contact with parents. Common examples include blogs written by or for teachers, blogs maintained for the purpose of classroom instruction, or blogs written about educational policy. Educators who blog are sometimes called edubloggers.

Transliteracy is "a fluidity of movement across a range of technologies, media and contexts". It is an ability to use diverse techniques to collaborate across different social groups.

Information and media literacy (IML) enables people to show and make informed judgments as users of information and media, as well as to become skillful creators and producers of information and media messages. IML is a combination of information literacy and media literacy. The transformative nature of IML includes creative works and creating new knowledge; to publish and collaborate responsibly requires ethical, cultural and social understanding.

The term digital citizen is used with different meanings. According to the definition provided by Karen Mossberger, one of the authors of Digital Citizenship: The Internet, Society, and Participation, digital citizens are "those who use the internet regularly and effectively." In this sense, a digital citizen is a person using information technology (IT) in order to engage in society, politics, and government.

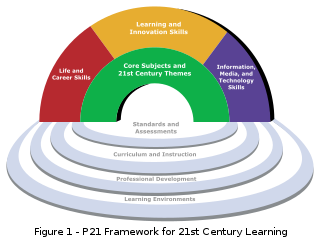

21st century skills comprise skills, abilities, and learning dispositions that have been identified as being required for success in 21st century society and workplaces by educators, business leaders, academics, and governmental agencies. This is part of a growing international movement focusing on the skills required for students to master in preparation for success in a rapidly changing, digital society. Many of these skills are also associated with deeper learning, which is based on mastering skills such as analytic reasoning, complex problem solving, and teamwork. These skills differ from traditional academic skills in that they are not primarily content knowledge-based.

Amy Burvall is an American educator known for her innovative teaching videos produced jointly with her colleague Herb Mahelona which describe historical events in song to the soundtrack of pop music hits. The videos were originally produced just for school use but have been viewed over one million times since they began to be published on YouTube.

Virtual exchange is an instructional approach or practice for language learning. It broadly refers to the "notion of 'connecting' language learners in pedagogically structured interaction and collaboration" through computer-mediated communication for the purpose of improving their language skills, intercultural communicative competence, and digital literacies. Although it proliferated with the advance of the internet and web 2.0 technologies in the 1990s, its roots can be traced to learning networks pioneered by Célestin Freinet in 1920s and, according to Dooly, even earlier in Jardine's work with collaborative writing at the University of Glasgow at the end of the 17th to the early 18th century.

The CRAAP test is a test to check the objective reliability of information sources across academic disciplines. CRAAP is an acronym for Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose. Due to a vast number of sources existing online, it can be difficult to tell whether these sources are trustworthy to use as tools for research. The CRAAP test aims to make it easier for educators and students to determine if their sources can be trusted. By employing the test while evaluating sources, a researcher can reduce the likelihood of using unreliable information. The CRAAP test, developed by Sarah Blakeslee and her team of librarians at California State University, Chico, is used mainly by higher education librarians at universities. It is one of various approaches to source criticism.

References

- ↑ "Renee Hobbs - University of Rhode Island - Professor and Founding Director" . Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ ERIC - Visual-Verbal Synchrony and Television News: Decreasing the Knowledge Gap., 1986-May-25. 1986-05-25. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ "1999 Felton Media Scholars Announced; Program Develops Skills to Critically Assess 'What You Watch, See and Read in the Media'. - Free Online Library". Thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ "Assignment: Media Literacy". Media Education Lab. 2013-02-24. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ "The Journal of Media Literacy Education is an online, open-access, peer-reviewed interdisciplinary journal that supports the development of research, scholarship and the pedagogy of media literacy education" (PDF). Jmle.org. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ Heitin, Liana (2016-11-09). "What Is Digital Literacy?". Education Week. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ Heitin, Liana (9 November 2016). "What Is Digital Literacy?". Education Week. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ↑ Nilsen, Ella (2016-12-04). "Media literacy class ever evolving". Concordmonitor.com. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ Tuzel, Sait; Hobbs, Renee (2017). "The Use of Social Media and Popular Culture to Advance Cross-Cultural Understanding". Comunicar (in Spanish). 25 (51): 63–72. doi: 10.3916/c51-2017-06 . ISSN 1134-3478.

- ↑ "About | National Association for Media Literacy Education". Namle.net. 2016-08-26. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ Goldstein, Dana (2017-02-02). "How to Inform a More Perfect Union". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339 . Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Renee, Hobbs; Sandra, McGee (2014). "Teaching about Propaganda: An Examination of the Historical Roots of Media Literacy". Journal of Media Literacy Education. 6 (2). ISSN 2167-8715.

- ↑ "Edited by Renee Hobbs: Exploring the Roots of Digital and Media Literacy through Personal Narrative". www.temple.edu. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "Digital and Media Literacy : A Plan of Action" (PDF). Mediaeducationlab.com. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ Boss, Suzie (2011-01-19). "Why Media Literacy is Not Just for Kids". Edutopia. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Kauffman, Gretel (22 November 2016). "Many teens have trouble spotting fake news, but it's not as bad as it sounds". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ↑ R Hobbs (2006-02-07). "The seven great debates in the media literacy movement - Hobbs - 1998". Journal of Communication. 48: 16–32. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1998.tb02734.x.

- ↑ "The Cost of Copyright Confusion for Media Literacy" (PDF). Macfound.org. September 2007. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ "Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Media Literacy Education" (PDF). Mediaeducationlab.com. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ Hobbs, R. (2014). "Exemption to the Prohibition of Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies. To the Copyright Office, Library of Congress. Reply Comments of Professor Renee Hobbs on Behalf of the Media Education Lab at the Harrington School of Communication and Media at the University of Rhode Island". Copyright.gov. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ "Media literacy class ever evolving". 2016-12-07.

- ↑ Hobbs, R.; Frost, R. (2003). "Measuring the acquisition of media literacy skills". Reading Research Quarterly. 38 (3): 330–354. doi:10.1598/rrq.38.3.2.

- ↑ Hobbs, R.; Donnelly, K.; Friesem, J.; Moen, M. (2013). "Learning to engage: How positive attitudes about the news, media literacy and video production contribute to adolescent civic engagement". Educational Media International. 50 (4): 231–246. doi:10.1080/09523987.2013.862364. S2CID 62652539.

- ↑ Martens, H.; Hobbs, R. (2015). "How media literacy supports civic engagement in a digital age". Atlantic Journal of Communication. 23 (2): 120–137. doi:10.1080/15456870.2014.961636. S2CID 52208620.

- ↑ Hobbs, R.; He, H.; RobbGrieco, M. (2014). "Seeing, believing and learning to be skeptical: Supporting language learning through advertising analysis activities". TESOL Journal. 6 (3): 447–475. doi:10.1002/tesj.153. S2CID 143292061.

- ↑ Hobbs, R.; Ebrahimi, A.; Cabral, N.; Yoon, J.; Al-Humaidan, R. (2011). "Field-based teacher education in elementary media literacy as a means to promote global understanding". Action in Teacher Education. 33 (2): 144–156. doi:10.1080/01626620.2011.569313. S2CID 153363358.

- ↑ Hobbs, R.; RobbGrieco, M. (2012). "African-American children's active reasoning about media texts as a precursor to media literacy". Journal of Children and Media. 6 (4): 502–519. doi:10.1080/17482798.2012.740413. S2CID 142591436.

- ↑ "Mind Over Media: Analyzing Contemporary Propaganda". Propaganda.mediaeducationlab.com. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ "What's Your Motivation?". Discover Media Literacy. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ "Home". Discover Media Literacy. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ↑ Hobbs, R. (1996). Know TV: Changing what, why and how you watch. [Video & curriculum]. Maryland State Department of Education and Discovery Communications, Inc.

- ↑ "Tuning in to Media: Literacy for the Information Age". Media Education Lab. Retrieved 2017-01-08.