Related Research Articles

Fifth Estate (FE) is a U.S. periodical, based in Detroit, Michigan, begun in 1965, and presently with staff members across North America who connect via the Internet. Its editorial collective sometimes has divergent views on the topics the magazine addresses but generally shares an anarchist, anti-authoritarian outlook and a non-dogmatic, action-oriented approach to change. The title implies that the periodical is an alternative to the fourth estate.

Green anarchism is an anarchist school of thought that puts a particular emphasis on environmental issues. A green anarchist theory is normally one that extends anarchism beyond a critique of human interactions and includes a critique of the interactions between humans and non-humans as well. This often culminates in an anarchist revolutionary praxis that is not merely dedicated to human liberation, but also to some form of nonhuman liberation and that aims to bring about an environmentally sustainable anarchist society. Important early influences were Henry David Thoreau, Leo Tolstoy and Élisée Reclus. In the late 19th century, green anarchism emerged within individualist anarchist circles in Cuba, France, Portugal and Spain.

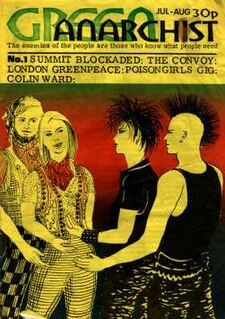

The Green Anarchist, established in 1984 in the UK, was a magazine advocating green anarchism: an explicit fusion of libertarian socialist and ecological thinking.

Anarchists have traditionally been skeptical of or vehemently opposed to organized religion. Nevertheless, some anarchists have provided religious interpretations and approaches to anarchism, including the idea that glorification of the state is a form of sinful idolatry.

The Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front, formerly known as the Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Federation (ZabFed), is a platformist–especifista anarchist political organisation in South Africa, based primarily in Johannesburg. The word zabalaza means "struggle" in isiZulu and isiXhosa. Initially, as ZabFed, it was a federation of pre-existing collectives, mainly in Soweto and Johannesburg. It is now a unitary organisation based on individual applications for membership, describing itself as a "federation of individuals". Historically the majority of members have been people of colour. Initially the ZACF had sections in both South Africa and Swaziland. The two sections were split in 2007, but the Swazi group faltered in 2008. Currently the ZACF also recruits in Zimbabwe. Members have historically faced repression in both Swaziland and South Africa.

Anarchism in South Africa dates to the 1880s, and played a major role in the labour and socialist movements from the turn of the twentieth century through to the 1920s. The early South African anarchist movement was strongly syndicalist. The ascendance of Marxism–Leninism following the Russian Revolution, along with state repression, resulted in most of the movement going over to the Comintern line, with the remainder consigned to irrelevance. There were slight traces of anarchist or revolutionary syndicalist influence in some of the independent left-wing groups which resisted the apartheid government from the 1970s onward, but anarchism and revolutionary syndicalism as a distinct movement only began re-emerging in South Africa in the early 1990s. It remains a minority current in South African politics.

Anarchism in the United States began in the mid-19th century and started to grow in influence as it entered the American labor movements, growing an anarcho-communist current as well as gaining notoriety for violent propaganda of the deed and campaigning for diverse social reforms in the early 20th century. By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed and anarcho-communism and other social anarchist currents emerged as the dominant anarchist tendency.

National-anarchism is a right-wing nationalist ideology which advocates racial separatism, racial nationalism, ethnonationalism and racial purity. National-anarchists claim to syncretize neotribal ethnic nationalism with philosophical anarchism, mainly in their support for a stateless society while rejecting anarchist social philosophy. The main ideological innovation of national-anarchism is its anti-state palingenetic ultranationalism. National-anarchists advocate homogeneous communities in place of the nation state. National-anarchists claim that those of different ethnic or racial groups would be free to develop separately in their own tribal communes while striving to be politically meritocratic, economically non-capitalist, ecologically sustainable and socially and culturally traditional.

Anarchism and nationalism both emerged in Europe following the French Revolution of 1789 and have a long and durable relationship going back at least to Mikhail Bakunin and his involvement with the pan-Slavic movement prior to his conversion to anarchism. There has been a long history of anarchist involvement with nationalism all over the world as well as with internationalism.

Troy Southgate is a British far-right political activist and a self-described national-anarchist. He has been affiliated with far-right and fascist groups, such as National Front and International Third Position, and is the founder and editor-in-chief of Black Front Press. Southgate's movement has been described as working to "exploit a burgeoning counter culture of industrial heavy metal music, paganism, esotericism, occultism and Satanism that, it believes, holds the key to the spiritual reinvigoration of western society ready for an essentially Evolian revolt against the culturally and racially enervating forces of American global capitalism."

New Right was a UK-based pan-European nationalist, far-right think tank founded by Troy Southgate and Jonathan Bowden. It was part of the French Nouvelle Droite movement, and was otherwise unrelated to the wider British and American usage of the term "New Right".

Anarchism in Japan began to emerge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as Western anarchist literature began to be translated into Japanese. It existed throughout the 20th century in various forms, despite repression by the state that became particularly harsh during the two world wars, and it reached its height in the 1920s with organisations such as Kokuren and Zenkoku Jiren.

The Spunk Library was an anarchist Internet archive. The name "spunk" was chosen for the term's meaning in Swedish, English, and Australian, summarized by the website as "nondescript, energetic, courageous and attractive".

Contemporary anarchism within the history of anarchism is the period of the anarchist movement continuing from the end of World War II and into the present. Since the last third of the 20th century, anarchists have been involved in anti-globalisation, peace, squatter and student protest movements. Anarchists have participated in violent revolutions such as in the Free Territory and Revolutionary Catalonia and anarchist political organizations such as the International Workers' Association and the Industrial Workers of the World exist since the 20th century. Within contemporary anarchism, the anti-capitalism of classical anarchism has remained prominent.

Golos Truda was a Russian-language anarchist newspaper. Founded by working-class Russian expatriates in New York City in 1911, Golos Truda shifted to Petrograd during the Russian Revolution in 1917, when its editors took advantage of the general amnesty and right of return for political dissidents. There, the paper integrated itself into the anarchist labour movement, pronounced the necessity of a social revolution of and by the workers, and situated itself in opposition to the myriad of other left-wing movements.

Eumeswil is a 1977 novel by the German author Ernst Jünger. The narrative is set in an undatable post-apocalyptic world, somewhere in present-day Morocco. It follows the inner and outer life of Manuel Venator, a historian in the city-state of Eumeswil who also holds a part-time job in the night bar of Eumeswil's ruling tyrant, the Condor. The book was published in English in 1993, translated by Joachim Neugroschel.

Anarchy is a society being freely constituted without authorities or a governing body. It may also refer to a society or group of people that entirely rejects a set hierarchy. The word Anarchy was first used in English in 1539, meaning "an absence of government". Pierre-Joseph Proudhon adopted anarchy and anarchist in his 1840 treatise What Is Property? to refer to anarchism, a new political philosophy and social movement which advocates stateless societies based on free and voluntary associations. Anarchists seek a system based on the abolishment of all coercive hierarchy and the creation of a system of direct democracy and worker cooperatives.

Platformism is a form of anarchist organization that seeks unity from its participants, having as a defining characteristic the idea that each platformist organization should include only people that are fully in agreement with core group ideas, rejecting people who disagree. It stresses the need for tightly organized anarchist organizations that are able to influence working class and peasant movements.

Collectivist anarchism, also referred to as anarchist collectivism and anarcho-collectivism, is a revolutionary socialist doctrine and anarchist school of thought that advocates the abolition of both the state and private ownership of the means of production as it envisions in its place the means of production being owned collectively whilst controlled and self-managed by the producers and workers themselves. Notwithstanding the name, collectivism anarchism is seen as a blend of individualism and collectivism.

Anarchism in the Czech Republic is a political movement in the Czech Republic, with its roots in the Bohemian Reformation, which peaked in the early 20th century. It later dissolved into the nascent Czech communist movement, before seeing a resurgence after the fall of the Fourth Czechoslovak Republic in the Velvet Revolution.

References

- ↑ An Interview with Richard Hunt

- ↑ For example, Richard Hunt, "Why Anarchism?", in The English Alternative 10 (1999)