Within economics, the concept of utility is used to model worth or value. Its usage has evolved significantly over time. The term was introduced initially as a measure of pleasure or happiness within the theory of utilitarianism by moral philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. The term has been adapted and reapplied within neoclassical economics, which dominates modern economic theory, as a utility function that represents a single consumer's preference ordering over a choice set but is not comparable across consumers. This concept of utility is personal and is based on choice rather than on the pleasure received, and so is more rigorously specified than the original concept but makes it less useful for ethical decisions.

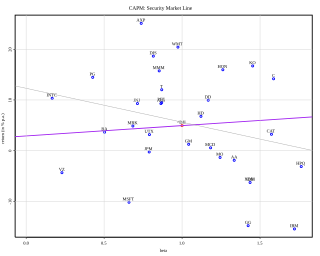

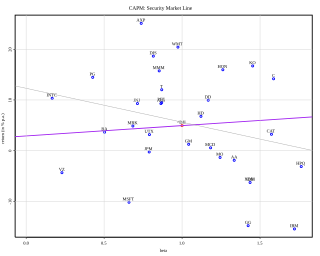

In finance, the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) is a model used to determine a theoretically appropriate required rate of return of an asset, to make decisions about adding assets to a well-diversified portfolio.

In economics and finance, risk aversion is the tendency of people to prefer outcomes with low uncertainty to those outcomes with high uncertainty, even if the average outcome of the latter is equal to or higher in monetary value than the more certain outcome. Risk aversion explains the inclination to agree to a situation with a more predictable, but possibly lower payoff, rather than another situation with a highly unpredictable, but possibly higher payoff. For example, a risk-averse investor might choose to put their money into a bank account with a low but guaranteed interest rate, rather than into a stock that may have high expected returns, but also involves a chance of losing value.

Prospect theory is a theory of behavioral economics and behavioral finance that was developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979. The theory was cited in the decision to award Kahneman the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics.

In economics and finance, risk neutral preferences are preferences that are neither risk averse nor risk seeking. A risk neutral party's decisions are not affected by the degree of uncertainty in a set of outcomes, so a risk neutral party is indifferent between choices with equal expected payoffs even if one choice is riskier. For example, if offered either or a chance each of and , a risk neutral person would have no preference. In contrast, a risk averse person would prefer the first offer, while a risk seeking person would prefer the second.

In mathematical finance, a risk-neutral measure is a probability measure such that each share price is exactly equal to the discounted expectation of the share price under this measure. This is heavily used in the pricing of financial derivatives due to the fundamental theorem of asset pricing, which implies that in a complete market a derivative's price is the discounted expected value of the future payoff under the unique risk-neutral measure. Such a measure exists if and only if the market is arbitrage-free.

The St. Petersburg paradox or St. Petersburg lottery is a paradox related to probability and decision theory in economics. It is based on a theoretical lottery game that leads to a random variable with infinite expected value but nevertheless seems to be worth only a very small amount to the participants. The St. Petersburg paradox is a situation where a naive decision criterion which takes only the expected value into account predicts a course of action that presumably no actual person would be willing to take. Several resolutions to the paradox have been proposed.

The expected utility hypothesis is a popular concept in economics that serves as a reference guide for decisions when the payoff is uncertain. The theory recommends which option rational individuals should choose in a complex situation, based on their risk appetite and preferences.

The Allais paradox is a choice problem designed by Maurice Allais (1953) to show an inconsistency of actual observed choices with the predictions of expected utility theory.

Stochastic dominance is a partial order between random variables. It is a form of stochastic ordering. The concept arises in decision theory and decision analysis in situations where one gamble can be ranked as superior to another gamble for a broad class of decision-makers. It is based on shared preferences regarding sets of possible outcomes and their associated probabilities. Only limited knowledge of preferences is required for determining dominance. Risk aversion is a factor only in second order stochastic dominance.

In decision theory and economics, ambiguity aversion is a preference for known risks over unknown risks. An ambiguity-averse individual would rather choose an alternative where the probability distribution of the outcomes is known over one where the probabilities are unknown. This behavior was first introduced through the Ellsberg paradox.

Cumulative prospect theory (CPT) is a model for descriptive decisions under risk and uncertainty which was introduced by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in 1992. It is a further development and variant of prospect theory. The difference between this version and the original version of prospect theory is that weighting is applied to the cumulative probability distribution function, as in rank-dependent expected utility theory but not applied to the probabilities of individual outcomes. In 2002, Daniel Kahneman received the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel for his contributions to behavioral economics, in particular the development of Cumulative Prospect Theory (CPT).

In economics and finance, exponential utility is a specific form of the utility function, used in some contexts because of its convenience when risk is present, in which case expected utility is maximized. Formally, exponential utility is given by:

Consumption smoothing is the economic concept used to express the desire of people to have a stable path of consumption. People desire to translate their consumption from periods of high income to periods of low income to obtain more stability and predictability. There exist many states of the world, which means there are many possible outcomes that can occur throughout an individual's life. Therefore, to reduce the uncertainty that occurs, people choose to give up some consumption today to prevent against an adverse outcome in the future. In order for one to adequately and properly prepare for unforeseen circumstances that can occur in the future, we must start planning today, putting money aside for when these unforeseen circumstances happen.

Cooperative bargaining is a process in which two people decide how to share a surplus that they can jointly generate. In many cases, the surplus created by the two players can be shared in many ways, forcing the players to negotiate which division of payoffs to choose. Such surplus-sharing problems are faced by management and labor in the division of a firm's profit, by trade partners in the specification of the terms of trade, and more.

In decision theory, the von Neumann–Morgenstern (VNM) utility theorem shows that, under certain axioms of rational behavior, a decision-maker faced with risky (probabilistic) outcomes of different choices will behave as if he or she is maximizing the expected value of some function defined over the potential outcomes at some specified point in the future. This function is known as the von Neumann–Morgenstern utility function. The theorem is the basis for expected utility theory.

In decision theory, economics, and finance, a two-moment decision model is a model that describes or prescribes the process of making decisions in a context in which the decision-maker is faced with random variables whose realizations cannot be known in advance, and in which choices are made based on knowledge of two moments of those random variables. The two moments are almost always the mean—that is, the expected value, which is the first moment about zero—and the variance, which is the second moment about the mean.

In mathematical economics, an isoelastic function, sometimes constant elasticity function, is a function that exhibits a constant elasticity, i.e. has a constant elasticity coefficient. The elasticity is the ratio of the percentage change in the dependent variable to the percentage causative change in the independent variable, in the limit as the changes approach zero in magnitude.

Intertemporal portfolio choice is the process of allocating one's investable wealth to various assets, especially financial assets, repeatedly over time, in such a way as to optimize some criterion. The set of asset proportions at any time defines a portfolio. Since the returns on almost all assets are not fully predictable, the criterion has to take financial risk into account. Typically the criterion is the expected value of some concave function of the value of the portfolio after a certain number of time periods—that is, the expected utility of final wealth. Alternatively, it may be a function of the various levels of goods and services consumption that are attained by withdrawing some funds from the portfolio after each time period.

Risk aversion is a preference for a sure outcome over a gamble with higher or equal expected value. Conversely, the rejection of a sure thing in favor of a gamble of lower or equal expected value is known as risk-seeking behavior.