Ambrosius Aurelianus was a war leader of the Romano-British who won an important battle against the Anglo-Saxons in the 5th century, according to Gildas. He also appeared independently in the legends of the Britons, beginning with the 9th-century Historia Brittonum. Eventually, he was transformed by Geoffrey of Monmouth into the uncle of King Arthur, the brother of Arthur's father Uther Pendragon, as a ruler who precedes and predeceases them both. He also appears as a young prophet who meets the tyrant Vortigern; in this guise, he was later transformed into the wizard Merlin.

Ælle is recorded in early sources as the first king of the South Saxons, reigning in what is now called Sussex, England, from 477 to perhaps as late as 514.

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman province of Britannia after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group that inhabited much of what is now England in the Early Middle Ages, and spoke Old English. They traced their origins to Germanic settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. Although the details are not clear, their cultural identity developed out of the interaction of these settlers with the pre-existing Romano-British culture. Over time, most of the people of what is now southern, central, northern and eastern England came to identify as Anglo-Saxon and speak Old English. Danish and Norman invasions later changed the situation significantly, but their language and political structures are the direct predecessors of the medieval Kingdom of England, and the Middle English language. Although the modern English language owes somewhat less than 26% of its words to Old English, this includes the vast majority of words used in everyday speech.

Strathclyde was a Brittonic kingdom in northern Britain during the Middle Ages. It comprised parts of what is now southern Scotland and North West England, a region the Welsh referred to as Yr Hen Ogledd. At its greatest extent in the 10th century, it stretched from Loch Lomond to the River Eamont at Penrith. Strathclyde seems to have been annexed by the Goidelic-speaking Kingdom of Alba in the 11th century, becoming part of the emerging Kingdom of Scotland.

Constantine III was a common Roman soldier who was declared emperor in Roman Britain in 407 and established himself in Gaul. He was recognised as co-emperor of the Roman Empire from 409 until 411.

The end of Roman rule in Britain was the transition from Roman Britain to post-Roman Britain. Roman rule ended in different parts of Britain at different times, and under different circumstances. In 383, the usurper Magnus Maximus withdrew troops from northern and western Britain, probably leaving local warlords in charge. In 407, usurper Constantine III took the remaining mobile Roman soldiers to Gaul in response to the crossing of the Rhine in late 406, leaving the island a victim to barbarian attacks. Around 410, the Romano-British expelled the Roman magistrates from Britain. Roman Emperor Honorius replied to a request for assistance with the Rescript of Honorius, telling the Roman cities to see to their own defence, a tacit acceptance of temporary British self-government. Honorius was fighting a large-scale war in Italy against the Visigoths under their leader Alaric, with Rome itself under siege. No forces could be spared to protect distant Britain. Though it is likely that Honorius expected to regain control over the provinces soon, by the mid-6th century Procopius recognised that Roman control of Britannia was entirely lost.

The Constitutio Antoniniana, also called the Edict of Caracalla or the Antonine Constitution, was an edict issued in AD 212 by the Roman emperor Caracalla. It declared that all free men in the Roman Empire were to be given full Roman citizenship.

Sub-Roman Britain is the period of late antiquity in Great Britain between the end of Roman rule and the Anglo-Saxon settlement. The term was originally used to describe archaeological remains found in 5th- and 6th-century AD sites that hinted at the decay of locally made wares from a previous higher standard under the Roman Empire. It is now used to describe the period that commenced with the recall of Roman troops to Gaul by Constantine III in 407 and to have concluded with the Battle of Deorham in 577.

The Britons, also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were the indigenous Celtic people who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age until the High Middle Ages, at which point they diverged into the Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons. They spoke Common Brittonic, the ancestor of the modern Brittonic languages.

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from soon after the end of Roman Britain until the Norman Conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom of England by King Æthelstan. It became part of the short-lived North Sea Empire of Cnut, a personal union between England, Denmark and Norway in the 11th century.

Anderitum was a Saxon Shore fort in the Roman province of Britannia. The ruins adjoin the west end of the village of Pevensey in East Sussex, England. The fort was built in the 290s and was abandoned after it was sacked in 471. It was re-inhabited by Saxons and in the 11th century the Normans built a castle within the east end of the fort.

In the early Roman Empire, from 30 BC to AD 212, a peregrinus was a free provincial subject of the Empire who was not a Roman citizen. Peregrini constituted the vast majority of the Empire's inhabitants in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. In AD 212, all free inhabitants of the Empire were granted citizenship by the Constitutio Antoniniana, with the exception of the dediticii, people who had become subject to Rome through surrender in war, and freed slaves.

Events from the 5th century in England.

In ancient Rome, the dediticii or peregrini dediticii were a class of free provincials who were neither slaves nor citizens holding either full Roman citizenship as cives or Latin rights as Latini.

British Latin or British Vulgar Latin was the Vulgar Latin spoken in Great Britain in the Roman and sub-Roman periods. While Britain formed part of the Roman Empire, Latin became the principal language of the elite and in the urban areas of the more romanised south and east of the island. In the less romanised north and west it never substantially replaced the Brittonic language of the indigenous Britons. In recent years, scholars have debated the extent to which British Latin was distinguishable from its continental counterparts, which developed into the Romance languages.

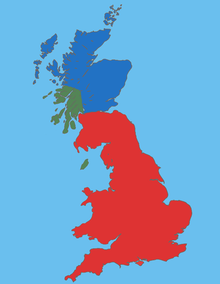

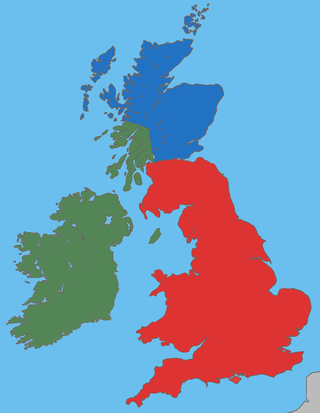

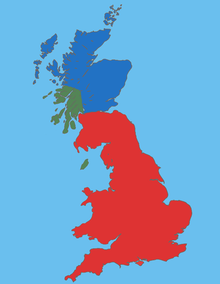

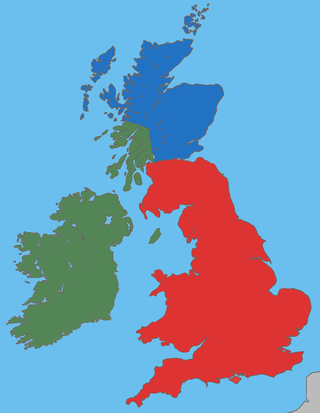

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain is the process which changed the language and culture of most of what became England from Romano-British to Germanic. The Germanic-speakers in Britain, themselves of diverse origins, eventually developed a common cultural identity as Anglo-Saxons. This process principally occurred from the mid-fifth to early seventh centuries, following the end of Roman rule in Britain around the year 410. The settlement was followed by the establishment of the Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the south and east of Britain, later followed by the rest of modern England, and the south-east of modern Scotland. The exact nature of this change is a topic of on-going research. Questions remain about the scale, timing and nature of the settlements, and also about what happened to the previous residents of what is now England.

The Insular Celts were speakers of the Insular Celtic languages in the British Isles and Brittany. The term is mostly used for the Celtic peoples of the isles up until the early Middle Ages, covering the British–Irish Iron Age, Roman Britain and Sub-Roman Britain. They included the Celtic Britons, the Picts, and the Gaels.

The frontier of the Roman Empire in Britain is sometimes styled Limes Britannicus by authors for the boundaries, including fortifications and defensive ramparts, that were built to protect Roman Britain. These defences existed from the 1st to the 5th centuries AD and ran through the territory of present-day England, Scotland and Wales.

Caer Gwinntguic was a late antique / early medieval British kingdom which had its center in the Roman city Venta Belgarum and the historic lands of the Belgae tribe. It acquired its own form of independence at the beginning of the fifth century as a result of the Rescript of Honorius, which left the inhabitants of the westernmost area of the Saxon Shore to organize their own defense.