A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel (aggregate) together. Cement mixed with fine aggregate produces mortar for masonry, or with sand and gravel, produces concrete. Concrete is the most widely used material in existence and is behind only water as the planet's most-consumed resource.

Portland cement is the most common type of cement in general use around the world as a basic ingredient of concrete, mortar, stucco, and non-specialty grout. It was developed from other types of hydraulic lime in England in the early 19th century by Joseph Aspdin, and is usually made from limestone. It is a fine powder, produced by heating limestone and clay minerals in a kiln to form clinker, grinding the clinker, and adding 2 to 3 percent of gypsum. Several types of portland cement are available. The most common, called ordinary portland cement (OPC), is grey, but white portland cement is also available. Its name is derived from its resemblance to portland stone which was quarried on the Isle of Portland in Dorset, England. It was named by Joseph Aspdin who obtained a patent for it in 1824. His son William Aspdin is regarded as the inventor of "modern" portland cement due to his developments in the 1840s.

Rosendale is a town in the center of Ulster County, New York, United States. It once contained a village Rosendale, primarily centered around Main Street, but which was dissolved through vote in 1977. The population was 5,782 at the 2020 census.

Rosendale is a hamlet located in the Town of Rosendale in Ulster County, New York, United States. The population was 1,285 at the 2020 census. It was also a census-designated place known as Rosendale Village until 2010, when the U.S. Census Bureau designated it Rosendale Hamlet. Some maps continue to list the place as just Rosendale. As of 2020, the "Hamlet" in the CDP name was dropped.

In materials science, a refractory is a material that is resistant to decomposition by heat or chemical attack that retains its strength and rigidity at high temperatures. They are inorganic, non-metallic compounds that may be porous or non-porous, and their crystallinity varies widely: they may be crystalline, polycrystalline, amorphous, or composite. They are typically composed of oxides, carbides or nitrides of the following elements: silicon, aluminium, magnesium, calcium, boron, chromium and zirconium. Many refractories are ceramics, but some such as graphite are not, and some ceramics such as clay pottery are not considered refractory. Refractories are distinguished from the refractory metals, which are elemental metals and their alloys that have high melting temperatures.

Lime is an inorganic material composed primarily of calcium oxides and hydroxides, usually calcium oxide and/or calcium hydroxide. It is also the name for calcium oxide which occurs as a product of coal-seam fires and in altered limestone xenoliths in volcanic ejecta. The International Mineralogical Association recognizes lime as a mineral with the chemical formula of CaO. The word lime originates with its earliest use as building mortar and has the sense of sticking or adhering.

Canvass White was an American engineer and inventor. He was chief engineer at the Delaware and Raritan Canal and he patented Rosendale cement, which became the dominant cement in the United States until 1900.

Rondout, is situated in Ulster County, New York on the Hudson River at the mouth of Rondout Creek. Originally a maritime village, the arrival of the Delaware and Hudson Canal helped create a city that dwarfed nearby Kingston. Rondout became the third largest port on the Hudson River. Rondout merged with Kingston in 1872. It now includes the Rondout–West Strand Historic District.

Cast stone or reconstructed stone is a highly refined building material, a form of precast concrete used as masonry intended to simulate natural-cut stone. It is used for architectural features: trim, or ornament; facing buildings or other structures; statuary; and for garden ornaments. Cast stone can be made from white and/or grey cements, manufactured or natural sands, crushed stone or natural gravels, and colored with mineral coloring pigments. Cast stone may replace such common natural building stones as limestone, brownstone, sandstone, bluestone, granite, slate, coral, and travertine.

The Wallkill Valley Rail Trail is a 23.7-mile (38.1 km) rail trail and linear park that runs along the former Wallkill Valley Railroad rail corridor in Ulster County, New York, United States. It stretches from Gardiner through New Paltz, Rosendale and Ulster to the Kingston city line, just south of a demolished, concrete Conrail railroad bridge that was located on a team-track siding several blocks south of the also-demolished Kingston New York Central Railroad passenger station. The trail is separated from the Walden–Wallkill Rail Trail by two state prisons in Shawangunk, though there have been plans to bypass these facilities and to connect the Wallkill Valley Rail Trail with other regional rail-trails. The northern section of the trail forms part of the Empire State Trail.

Roman cement is a substance developed by James Parker in the 1780s, being patented in 1796.

The Rosendale Library, formerly the All Saints' Chapel, is located on Main Street in Rosendale, New York, United States. It was originally built as a Gothic Revival Episcopal church from locally mined Rosendale cement, a material which covers the stonework exterior walls.

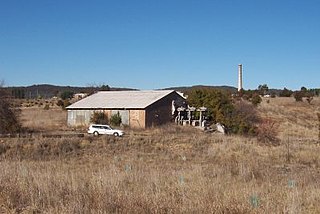

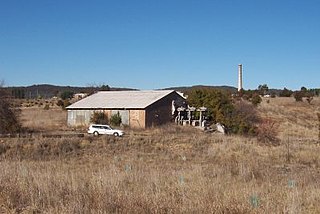

The Snyder Estate Natural Cement Historic District is located in the Town of Rosendale, New York, United States. It is a 275-acre (111 ha) tract roughly bounded by Rondout Creek, Binnewater and Cottekill roads and Sawdust Avenue. NY 213 runs through the lower portion of the district, paralleling the dry bed of the Delaware and Hudson Canal.

Magnesium oxide, more commonly called magnesia, is a mineral that when used as part of a cement mixture and cast into thin cement panels under proper curing procedures and practices can be used in residential and commercial building construction. Some versions are suitable for general building uses and for applications that require fire resistance, mold and mildew control, as well as sound control applications. Magnesia board has strength and resistance due to very strong bonds between magnesium and oxygen atoms that form magnesium oxide crystals.

The Rosendale Trestle is a 940-foot (290-meter) continuous truss bridge and former railroad trestle in Rosendale Village, a hamlet in the town of Rosendale in Ulster County, New York. Originally constructed by the Wallkill Valley Railroad to continue its rail line from New Paltz to Kingston, the bridge rises 150 ft (46 m) above Rondout Creek, spanning both Route 213 and the former Delaware and Hudson Canal. Construction on the trestle began in late 1870, and continued until early 1872. When it opened to rail traffic on April 6, 1872, the Rosendale trestle was the highest span bridge in the United States.

Joppenbergh Mountain is a nearly 500-foot (152 m) mountain in Rosendale Village, a hamlet in the town of Rosendale, in Ulster County, New York. The mountain is composed of a carbonate bedrock overlain by glacially deposited material. It was named after Rosendale's founder, Jacob Rutsen, and mined throughout the late 19th century for dolomite that was used in the manufacture of natural cement. Extensive mining caused a large cave-in on December 19, 1899, that destroyed equipment and collapsed shafts within Joppenbergh. Though it was feared that several workers had been killed, the collapse happened while all the miners were outside, eating lunch. Since the collapse, the mountain has experienced shaking and periodic rockfalls.

The Edison Portland Cement Company was a venture by Thomas Edison that helped to improve the Portland cement industry. Edison was developing an iron ore milling process and discovered a market in the sale of waste sand to cement manufacturers. He decided to set up his own cement company, founding it in New Village, New Jersey in 1899, and went on to supply the concrete for the construction of Yankee Stadium in 1922.

The Edison Ore-Milling Company was a venture by Thomas Edison that began in 1881. Edison introduced some significant technological developments to the iron ore milling industry but the company ultimately proved to be unprofitable. Towards the end of the company's life, Edison realized the potential application of his technologies to the cement industry and formed the Edison Portland Cement Company in 1899.

Raffan's Mill and Brick Bottle Kilns is a heritage-listed lime kiln at Carlton Road, Portland, New South Wales, Australia. It was built from 1884 to 1895 by George Raffan and Alexander Currie. It is also known as Raffan's Mill and Brick Bottle Kilns Precinct, Portland Cement Works Site, Williwa Street Portland. The property is owned by Boral. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 3 August 2012.

Widow Jane Mine is a former cement mine located west of Rosendale, New York. The mine was active from 1825 to 1970 and is now part of the Snyder Estate Natural Cement Historic District. Dolomite extracted from the mine was used to make Rosendale cement which was widely used in the 19th century, contributing to the base of the Statue of Liberty among other structures.