Related Research Articles

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execution of Charles I. The republic's existence was declared through "An Act declaring England to be a Commonwealth", adopted by the Rump Parliament on 19 May 1649. Power in the early Commonwealth was vested primarily in the Parliament and a Council of State. During the period, fighting continued, particularly in Ireland and Scotland, between the parliamentary forces and those opposed to them, in the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and the Anglo-Scottish war of 1650–1652.

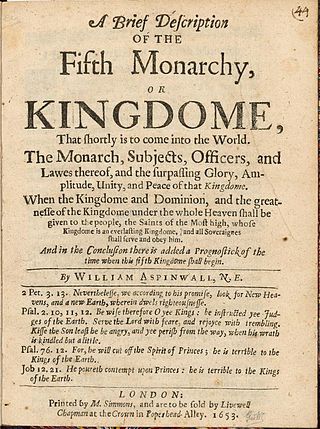

The Fifth Monarchists, or Fifth Monarchy Men, were a Protestant sect which advocated Millennialist views, active during the 1649 to 1660 Commonwealth of England. Named after a prophecy in the Book of Daniel that Four Monarchies would precede the Fifth or establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth, the group was one of a number of Nonconformist sects that emerged during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Perhaps its best known adherent was Major-General Thomas Harrison, executed in October 1660 as a regicide, while Oliver Cromwell was a sympathiser until 1653.

Oliver Cromwell was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of the British Isles. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially as a senior commander in the Parliamentarian army and latterly as a politician. A leading advocate of the execution of Charles I in January 1649, which led to the establishment of The Protectorate, he ruled as Lord Protector from December 1653 until his death in September 1658. Cromwell remains a controversial figure due to his use of the army to acquire political power, and the brutality of his 1649 campaign in Ireland.

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, is the period from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659 during which England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and associated territories were joined together in the Commonwealth of England, governed by a Lord Protector. It began when Barebone's Parliament was dismissed, and the Instrument of Government appointed Oliver Cromwell Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. Cromwell died in September 1658 and was succeeded by his son Richard Cromwell.

Major-General William Goffe, probably born between 1613 and 1618, died c. 1679, was an English Parliamentarian soldier who served with the New Model Army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A religious radical nicknamed “Praying William” by contemporaries, he approved the Execution of Charles I in January 1649, and later escaped prosecution as a regicide by fleeing to New England.

Pride's Purge is the name commonly given to an event that took place on 6 December 1648, when soldiers prevented members of Parliament considered hostile to the New Model Army from entering the House of Commons of England.

The Anglo-Spanish War was a conflict between the English Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell, and Spain, between 1654 and 1660. It was caused by commercial rivalry. Each side attacked the other's commercial and colonial interests in various ways such as privateering and naval expeditions. In 1655, an English amphibious expedition invaded Spanish territory in the Caribbean. In 1657, England formed an alliance with France, merging the Anglo–Spanish war with the larger Franco-Spanish War resulting in major land actions that took place in the Spanish Netherlands.

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms, sometimes known as the British Civil Wars, were a series of intertwined conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bishops' Wars, the First and Second English Civil Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and the Anglo-Scottish war (1650–1652). They resulted in victory for the Parliamentarian army, the execution of Charles I, the abolition of monarchy, and founding of the Commonwealth of England, a unitary state which controlled the British Isles until the Stuart Restoration in 1660.

The Anglo-Scottish war (1650–1652), also known as the Third Civil War, was the final conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between shifting alliances of religious and political factions in England, Scotland and Ireland.

Colonel John Hewson, also spelt Hughson, was a shoemaker from London and religious Independent who fought for Parliament and the Commonwealth in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, reaching the rank of colonel. Considered one of Oliver Cromwell's most reliable supporters within the New Model Army, his unit played a prominent part in Pride's Purge of December 1648. Hewson signed the death warrant for the Execution of Charles I in January 1649, for which he reportedly sourced the headsman, while soldiers from his regiment provided security.

Francis Rous, also spelled Rouse, was an English politician and Puritan religious author, who was Provost of Eton from 1644 to 1659, and briefly Speaker of the House of Commons in 1653.

The Battle of Inverkeithing was fought on 20 July 1651 between an English army under John Lambert and a Scottish army led by James Holborne as part of an English invasion of Scotland. The battle was fought near the isthmus of the Ferry Peninsula, to the south of Inverkeithing, after which it is named.

The Interregnum was the period between the execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649 and the arrival of his son Charles II in London on 29 May 1660 which marked the start of the Restoration. During the Interregnum, England was under various forms of republican government.

Colonel John Okey was a political and religious radical who served in the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A regicide who approved the Execution of Charles I in 1649, he escaped to the Dutch Republic after the 1660 Stuart Restoration, but was brought back to England and executed on 19 April 1662.

The Battle of Hieton was fought on the 1 December 1650 between a force of Scottish Remonstrants under Colonel Gilbert Ker and 1,000 English commanded by Major-general John Lambert. The site of the battle was by the Cadzow Burn, near the present day town centre of Hamilton, Scotland. The Scots attacked, surprising the English, but were beaten back and destroyed as a fighting force. The battle was part of the Anglo-Scottish war of 1650–1652.

Henry Scobell was an English Parliamentary official, and editor of official publications. He was clerk to the Long Parliament, and wrote on parliamentary procedure and precedents.

James Berry, died 9 May 1691, was a Clerk from the West Midlands who served with the Parliamentarian army in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Characterised by a contemporary and friend as "one of Cromwell's favourites", during the 1655 to 1657 Rule of the Major-Generals, he was administrator for Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Shropshire and Wales.

Hezekiah Haynes supported the parliamentary cause during the English Civil War rising to the rank of major. During the Interregnum, under the patronage of his war time commander General Charles Fleetwood, he held a number of administrative posts in the under the early Commonwealth and Protectorate. He supported his old general during the late Commonwealth, and after spending 18 months in prison during the first couple of years of the Restoration, he retired to the family estate of Copford Hall in Essex.

The interregnum in the British Isles began with the execution of Charles I in January 1649 and ended in May 1660 when his son Charles II was restored to the thrones of the three realms, although he had been already acclaimed king in Scotland since 1649. During this time the monarchial system of government was replaced with the Commonwealth of England.

The siege of Dundee took place from 23 August to 1 September 1651 during the 1650 to 1652 Anglo-Scottish war, with English Commonwealth forces under George Monck confronting a garrison commanded by Robert Lumsden. After a two-day artillery bombardment, the town was captured and looted on 1 September, with an estimated 100 to 500 killed, including Lumsden.

References

- Barnard, T. C. (2014), The English Republic 1649–1660, Routledge, ISBN 978-1317897262

- Bremer, Francis J.; Webster, Tom (2006), "Major-Generals", Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America, ABC-CLIO, p. 452, ISBN 978-1-57607-678-1

- Durston, Christopher (2001), Cromwell's Major-Generals: Godly Government During the English Revolution, Manchester University Press, p. 21, ISBN 978-0-7190-6065-6

- Hill, Christopher (1985), The Collected Essays of Christopher Hill, Harvester Press, ISBN 0710805128

- Little, Paterick (1 January 2007), "Putting the Protector back into the Protectorate", BBC History Magazine, 8 (1): 15

- Little, Patrick (2012), "Major-generals (act. 1655–1657)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95468 (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Royle, Trevor (2006) [2004], Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638–1660, Pub Abacus, ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1

- Smith, David Lee (2008), Cromwell and the Interregnum: The Essential Readings, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1405143141

- Smith, Laceyey Baldwin (2006), English History Made Brief, Irreverent, and Pleasurable, Chicago Review Press, ISBN 0897336305

- Wolf, John Baptiste (1962), The Emergence of European Civilization: From the Middle Ages to the Opening of the Nineteenth Century, Harper

- Woolrych, Austin (2004), Britain in Revolution: 1625–1660, Oxford University Press

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Firth, Charles (1900). "Worsley, Charles". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography . Vol. 63. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 32–33.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Firth, Charles (1900). "Worsley, Charles". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography . Vol. 63. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 32–33.- This article incorporates text from a publication under version 3.0 of the British Open Government Licence which is a Wikipedia compatible copyleft licence: "Civil War – What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? – Cromwell in his own words – Source 3", The National Archives, retrieved 11 September 2015