Russian humour gains much of its wit from the inflection of the Russian language, allowing for plays on words and unexpected associations. As with any other culture's humour, its vast scope ranges from lewd jokes and wordplay to political satire. [1]

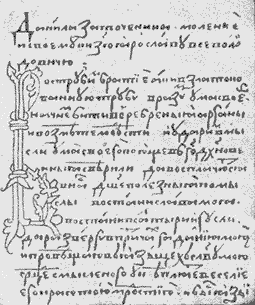

According to Dmitry Likhachov, Russian comedy traditions in literature could be traced back to Praying of Daniel the Immured by Daniil Zatochnik, a Pereyaslavl-born lower class writer who lived between the 12th and 13th centuries. [2] [3] However, it wasn't until the early 17th century when comedy developed into a separate genre as a reaction to the Time of Troubles. A whole line of independent anonymously published works gained popularity; the term "democratic satire" is used by researchers to describe them. [2] All had close ties to the folklore of Russia and were rewritten both in prose and as poems, including nebylitsa (a variation of nursery rhymes).

Most famous are The Tale of Yersh Yershovich and The Tale of Shemyaka's Trial that satirized the Russian judicial system: the first described a trial against a sleazy ruffe, with different fish representing different social classes, while the second focused on a corrupted judge Shemyaka who is often linked to Dmitry Shemyaka. [4] [2] Another outstanding work, The Tale of Frol Skobeev , was inspired by picaresque novels. Satire on Church was also very popular (The Tale of Savva the Priest, The Kalyazin Petition, The Tavern Service) which included parodies of religious texts. Mikhail Bakhtin and Dmitry Likhachov agreed on that many tales were created by low-ranking clergy who made fun of the form rather than content. [5] There were also straight-up parodies of literary genres such as The Story of a Life in Luxury and Fun. [2]

Lubok was one of the earliest known forms of popular print in Russia which rose to popularity around the same time. Similar to comic strips, it depicted various — often humorous — anecdotes as primitivistic pictures with captions. Among the common characters was The Cat of Kazan which appeared in one of the most famous lubki The Mice Are Burying the Cat described by various researchers as a parody on the funeral of Peter the Great, a celebration of Russian victories over the Tatars during the late 16th century or simply an illustration to an old fairy tale. [6] [7]

Next century saw the rise of a number of prominent comedy writers who belonged to the upper class. The most renowned is Denis Fonvizin who produced several comedy plays between 1769 and 1792, most famously The Minor (1781) about a nobleman without a high school diploma. It satirized provincial nobility and became a great success and a source of many quotes, inspiring many future generations of writers. [8] [9] Other names include Antiochus Kantemir who wrote satirical poems and a dramatist Alexander Sumarokov whose plays varied from a straight-up satire against his enemies to comedy of manners as well as the Russian Empress Catherine the Great who produced around 20 comedy plays and operas, most famously Oh, These Time! (1772) and The Siberian Shaman (1786). [9]

During the second half of the 18th century satirical magazines rose to popularity, providing social and political commentary. Those included Pochta dukhov (Spirits Mail) and Zritel (The Spectator) by Ivan Krylov who later turned into the leading Russian fabulist, Zhivopisets (The Painter) and Truten (The Drone) by Nikolay Novikov and even Vsyakaya vsyachina (All Sorts) established and edited by Catherine the Great herself. [10] [11] Alexander Afanasyev's 1859 monograph Russian Satirical Magazines of 1769—1774 became an in-depth research on this period and inspired a famous critical essay Russian satire during the times of Catherine by Nikolay Dobrolyubov who argued that the 18th-century satire wasn't sharp or influential enough and didn't lead to necessary socio-political changes. [12] [13]

The most popular form of Russian humour consists of jokes (анекдоты — anekdoty), which are short stories with a punch line. Typical of Russian joke culture is a series of categories with fixed and highly familiar settings and characters. Surprising effects are achieved by an endless variety of plots and plays on words. [14]

Drinking toasts can take the form of anecdotes or not-so-short stories, which tend to have a jocular or paradoxical conclusion, and ending with "So here's to, let's drink for the..." with a witty punchline referring to the initial story. [15]

A specific form of humour is chastushkas, songs composed of four-line rhymes, usually of black, sarcastic, humoristic, or satiric content.

Apart from jokes, Russian humour is very sarcastic and it is expressed in word play. Sometimes there are short poems including nonsense and black humour verses, similar to the Little Willie rhymes by Harry Graham, or, less so, Edward Lear's literary "nonsense verse". [16]

Often they have recurring characters such as "little boy", "Vova", "a girl", "Masha". Most rhymes involve death or a painful experience either for the protagonists or other people. This type of joke is especially popular with children. [16]

|

|

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or exposing the perceived flaws of individuals, corporations, government, or society itself into improvement. Although satire is usually meant to be humorous, its greater purpose is often constructive social criticism, using wit to draw attention to both particular and wider issues in society.

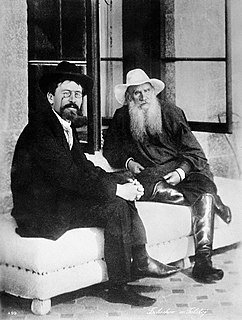

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia and its émigrés and to Russian-language literature. The roots of Russian literature can be traced to the Middle Ages, when epics and chronicles in Old East Slavic were composed. By the Age of Enlightenment, literature had grown in importance, and from the early 1830s, Russian literature underwent an astounding golden age in poetry, prose and drama. Romanticism permitted a flowering of poetic talent: Vasily Zhukovsky and later his protégé Alexander Pushkin came to the fore. Prose was flourishing as well. Mikhail Lermontov was one of the most important poets and novelists. The first great Russian novelist was Nikolai Gogol. Then came Ivan Turgenev, who mastered both short stories and novels. Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy soon became internationally renowned. Other important figures of Russian realism were Ivan Goncharov, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin and Nikolai Leskov. In the second half of the century Anton Chekhov excelled in short stories and became a leading dramatist. The beginning of the 20th century ranks as the Silver Age of Russian poetry. The poets most often associated with the "Silver Age" are Konstantin Balmont, Valery Bryusov, Alexander Blok, Anna Akhmatova, Nikolay Gumilyov, Sergei Yesenin, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Marina Tsvetaeva. This era produced some first-rate novelists and short-story writers, such as Aleksandr Kuprin, Nobel Prize winner Ivan Bunin, Leonid Andreyev, Fyodor Sologub, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Alexander Belyaev, Andrei Bely and Maxim Gorky.

Mikhail Yevgrafovich Saltykov-Shchedrin, born Mikhail Yevgrafovich Saltykov and known during his lifetime by the pen name Nikolai Shchedrin, was a major Russian writer and satirist of the 19th century. He spent most of his life working as a civil servant in various capacities. After the death of poet Nikolay Nekrasov he acted as editor of the well-known Russian magazine, Otechestvenniye Zapiski, until the Tsarist government banned it in 1884. In his works Saltykov mastered both stark realism and satirical grotesque merged with fantasy. His political novel The History of a Town (1870) is regarded as a satirical masterpiece, while the novel The Golovlyov Family (1880) became one of the major works of Russian realism and 19th-century fiction.

Nikolay Alexeyevich Nekrasov was a Russian poet, writer, critic and publisher, whose deeply compassionate poems about peasant Russia made him the hero of liberal and radical circles of Russian intelligentsia, as represented by Vissarion Belinsky, Nikolay Chernyshevsky and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. He is credited with introducing into Russian poetry ternary meters and the technique of dramatic monologue. As the editor of several literary journals, notably Sovremennik, Nekrasov was also singularly successful and influential.

The Prayer of Daniil Zatochnik, also translated as The Supplication of Daniel the Exile or Praying of Daniel the Immured, is an Old East Slavic text created by the Pereyaslavl-born writer Daniil Zatochnik during the 13th century.

Canadian humour is an integral part of the Canadian identity. There are several traditions in Canadian humour in both English and French. While these traditions are distinct and at times very different, there are common themes that relate to Canadians' shared history and geopolitical situation in North America and the world. Though neither universally kind nor moderate, humorous Canadian literature has often been branded by author Dick Bourgeois-Doyle as "gentle satire," evoking the notion embedded in humorist Stephen Leacock's definition of humour as "the kindly contemplation of the incongruities of life and the artistic expression thereof."

Dmitriy Yurievich Shemyaka was the second son of Yury of Zvenigorod by Anastasia of Smolensk and grandson of Dmitri Donskoi. His hereditary patrimony was the rich Northern town Galich-Mersky. Shemyaka was twice Grand Prince of Moscow.

Dmitry Sergeyevich Likhachov was a Russian medievalist, linguist, and a former labor camp prisoner. During his lifetime, Likhachov was considered the world's foremost scholar of the Old Russian language and its literature.

Denis Ivanovich Fonvizin was a playwright and writer of the Russian Enlightenment, one of the founders of literary comedy in Russia. His main works are two satirical comedies, one of them Young ignoramus, which mock contemporary Russian gentry and are still staged today.

Science fiction and fantasy have been part of mainstream Russian literature since the 19th century. Russian fantasy developed from the centuries-old traditions of Slavic mythology and folklore. Russian science fiction emerged in the mid-19th century and rose to its golden age during the Soviet era, both in cinema and literature, with writers like the Strugatsky brothers, Kir Bulychov, and Mikhail Bulgakov, among others. Soviet filmmakers, such as Andrei Tarkovsky, also produced many science fiction and fantasy films. With the fall of the Iron Curtain, modern Russia experienced a renaissance of fantasy. Outside modern Russian borders, there are a significant number of Russophone writers and filmmakers from Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan, who have made a notable contribution to the genres.

Comedy is a genre of fiction that consists of discourses or works intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, film, stand-up comedy, television, radio, books, or any other entertainment medium. The term originated in ancient Greece: in Athenian democracy, the public opinion of voters was influenced by political satire performed by comic poets in theaters. The theatrical genre of Greek comedy can be described as a dramatic performance pitting two groups, ages, genders, or societies against each other in an amusing agon or conflict. Northrop Frye depicted these two opposing sides as a "Society of Youth" and a "Society of the Old". A revised view characterizes the essential agon of comedy as a struggle between a relatively powerless youth and the societal conventions posing obstacles to his hopes. In this struggle, the youth then becomes constrained by his lack of social authority, and is left with little choice but to resort to ruses which engender dramatic irony, which provokes laughter.

The Muscovite Civil War, or Great Feudal War, was a prolonged conflict that cast its shadow over the entire reign of Vasily II of Moscow. The two warring parties were Vasily II, the Grand Prince of Moscow, as one party, and his uncle, Yury Dmitrievich, the Prince of Zvenigorod, and the sons of Yuri Dmitrievich, Vasily Kosoy and Dmitry Shemyaka, as the other party. In the intermediate stage, the party of Yury conquered Moscow, but in the end, Vasily II regained his crown. It was the first civil war in the history of Muscovy, whose largely peaceful rise had been predicated on a lack of conflict within the ruling family.

Professor Varvara Pavlovna Adrianova-Peretz was a Soviet and Russian philologist and medievalist specializing in Old Russian literature, folklore, and hagiography. She was a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR (1926) and of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union (1943).

The Battle of Belyov was fought in 1437 near Belyov between the troops of the Grand Duchy of Moscow under the command of Dmitry Shemyaka and Tatars led by Ulugh Muhammad. The result of the battle was the complete defeat of the Russian army.

Dmitriy Yurievich Krasny, was a Russian nobleman, the youngest son of Yury of Zvenigorod and Anastasia of Smolensk, and grandson of Dmitry Donskoy. He was the appanage prince of Galich-Mersky and took part in the Great Feudal War. The strange circumstances of his death are described in chronicles with many details and cause speculation about possible poisoning.

Satire is a television and film genre in the fictional or pseudo-fictional category that employs satirical techniques, be it of a political, religious, or social variety. Works using satire are often seen as controversial or taboo in nature, with topics such as race, class, system, violence, sex, war, and politics, criticizing or commenting on them, typically under the disguise of other genres including, but not limited to, comedies, dramas, parodies, fantasies and/or science fiction.

Letopis is a literary genre of Kievan Rus', written in Old East Slavic. It was also distributed in the Czech lands, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Lithuania and Latvia.