SS Great Britain is a museum ship and former passenger steamship that was advanced for her time. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1845 to 1853. She was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859), for the Great Western Steamship Company's transatlantic service between Bristol and New York City. While other ships had been built of iron or equipped with a screw propeller, Great Britain was the first to combine these features in a large ocean-going ship. She was the first iron steamer to cross the Atlantic Ocean, which she did in 1845, in 14 days.

Cunard Line is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its four ships have been registered in Hamilton, Bermuda.

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships came into practical usage during the early 1800s; however, there were exceptions that came before. Steamships usually use the prefix designations of "PS" for paddle steamer or "SS" for screw steamer. As paddle steamers became less common, "SS" is incorrectly assumed by many to stand for "steamship". Ships powered by internal combustion engines use a prefix such as "MV" for motor vessel, so it is not correct to use "SS" for most modern vessels.

The Blue Riband is an unofficial accolade given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest average speed. The term was borrowed from horse racing and was not widely used until after 1910. The record is based on average speed rather than passage time because ships follow different routes. Also, eastbound and westbound speed records are reckoned separately, as the more difficult westbound record voyage, against the Gulf Stream and the prevailing weather systems, typically results in lower average speeds.

Transatlantic crossings are passages of passengers and cargo across the Atlantic Ocean between Europe or Africa and the Americas. The majority of passenger traffic is across the North Atlantic between Western Europe and North America. Centuries after the dwindling of sporadic Viking trade with Markland, a regular and lasting transatlantic trade route was established in 1566 with the Spanish West Indies fleets, following the voyages of Christopher Columbus.

An ocean liner is a type of passenger ship primarily used for transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes. Only one ocean liner remains in service today.

SS City of Glasgow of 1850 was a single-screw passenger steamship of the Inman Line, which disappeared en route from Liverpool to Philadelphia in March 1854 with 480 passengers and crew. Based on ideas pioneered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel's SS Great Britain of 1845, City of Glasgow established that Atlantic steamships could be operated profitably without government subsidy. After a refit in 1852, she was also the first Atlantic steamship to carry steerage passengers, representing a significant improvement in the conditions experienced by immigrants. In March 1854 City of Glasgow vanished at sea with no known survivors.

The shipping company is an outcome of the development of the steamship. In former days, when the packet ship was the mode of conveyance, combinations, such as the well-known Dramatic and Black Ball lines, existed but the ships which they ran were not necessarily owned by the organizers of the services. The advent of the steamship changed all that.

The Inman Line was one of the three largest 19th-century British passenger shipping companies on the North Atlantic, along with the White Star Line and Cunard Line. Founded in 1850, it was absorbed in 1893 into American Line. The firm's formal name for much of its history was the Liverpool, Philadelphia and New York Steamship Company, but it was also variously known as the Liverpool and Philadelphia Steamship Company, as Inman Steamship Company, Limited, and, in the last few years before absorption, as the Inman and International Steamship Company.

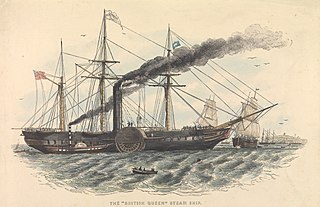

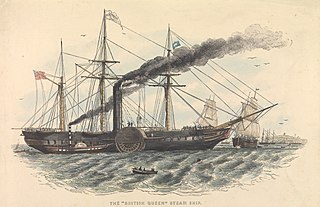

British Queen was a British passenger liner that was the second steamship completed for the transatlantic route when she was commissioned in 1839. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1839 to 1840, then being passed by the SS President. She was named in honor of Queen Victoria and owned by the British and American Steam Navigation Company. British Queen would have been the first transatlantic steamship had she not been delayed by 18 months because of the liquidation of the firm originally contracted to build her engine.

SS Sirius was a wooden-hulled sidewheel steamship built in 1837 by Robert Menzies & Sons of Leith, Scotland for the London-Cork route operated by the Saint George Steam Packet Company. The next year, she opened transatlantic steam passenger service when she was chartered for two voyages by the British and American Steam Navigation Company. By arriving in New York a day ahead of the Great Western, she is usually listed as the first holder of the Blue Riband, although the term was not used until decades later.

The Great Western Steam Ship Company operated the first regular transatlantic steamer service from 1838 until 1846. Related to the Great Western Railway, it was expected to achieve the position that was ultimately secured by the Cunard Line. The firm's first ship, Great Western was capable of record Blue Riband crossings as late as 1843 and was the model for Cunard's Britannia and her three sisters. The company's second steamer, the Great Britain was an outstanding technical achievement of the age. The company collapsed because it failed to secure a mail contract and Great Britain appeared to be a total loss after running aground. The company might have had a more successful outcome had it built sister ships for Great Western instead of investing in the too advanced Great Britain.

The British and American Steam Navigation Company was a steamship line that operated a regular transatlantic service from 1839 to 1841. Before its first purpose-built Atlantic liner, British Queen was completed, British and American chartered Sirius for two voyages in 1838 to beat the Great Western Steamship Company into service. B & A's regular liners were larger than their rivals, but were underpowered. The company collapsed when its second vessel, President was lost in 1841.

SS Archimedes was a steamship built in Britain in 1839. She was the world's first steamship to be driven successfully by a screw propeller.

Persia was a British passenger liner operated by the Cunard Line that won the Blue Riband in 1856 for the fastest westbound transatlantic voyage. She was the first Atlantic record breaker constructed of iron and was the largest ship in the world at the time of her launch. However, the inefficiencies of paddle wheel propulsion rendered Persia obsolete and she was taken out of service in 1868 after only twelve years. Attempts to convert Persia to sail were unsuccessful and the former pride of the British merchant marine was scrapped in 1872.

The Britannia class was the Cunard Line's initial fleet of wooden paddlers that established the first year round scheduled Atlantic steamship service in 1840. By 1845, steamships carried half of the transatlantic saloon passengers and Cunard dominated this trade. While the units of the Britannia class were solid performers, they were not superior to many of the other steamers being placed on the Atlantic at that time. What made the Britannia class successful is that it was the first homogeneous class of transatlantic steamships to provide a frequent and uniform service. Britannia, Acadia and Caledonia entered service in 1840 and Columbia in 1841 enabling Cunard to provide the dependable schedule of sailings required under his mail contracts with the Admiralty. It was these mail contracts that enabled Cunard to survive when all of his early competitors failed.

The America class was the replacement for the Britannia class, the Cunard Line's initial fleet of wooden paddle steamers. Entering service starting in 1848, these six vessels permitted Cunard to double its schedule to weekly departures from Liverpool, with alternating sailings to New York. The new ships were also designed to meet new competition from the United States.

SS President was a British passenger liner that was the largest ship in the world when she was commissioned in 1840, and the first steamship to founder on the transatlantic run when she was lost at sea with all 136 onboard in March 1841. She was the largest passenger ship in the world from 1840 to 1841. The ship's owner, the British and American Steam Navigation Company, collapsed as a result of the disappearance.

Vice-Admiral James Hosken was a British naval officer and a pioneer of ocean steam navigation. He joined the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars, and after more than 20 years of service left to join the merchant navy and serve as captain of the steamships SS Great Western and the SS Great Britain. He returned to the Royal Navy to see service during the Crimean War.

William Patterson Shipbuilders was a major shipbuilder in Bristol, England during the 19th century and an innovator in ship construction, producing both the SS Great Western and SS Great Britain, fine lined yachts and a small number of warships.