Quintus Horatius Flaccus, commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his Odes as just about the only Latin lyrics worth reading: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words."

The Roman Republic was the era of classical Roman civilization beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom and ending in 27 BC with the establishment of the Roman Empire. During this period, Rome's control expanded from the city's immediate surroundings to hegemony over the entire Mediterranean world.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to ancient Rome:

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the Roman army, fighting in Africa during the Third Punic War and in Spain during the Numantine War.

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Gaius Julius Caesar. The republican constitution had many veto points. In order to bypass constitutional obstacles and force through the political goals of the three men, they forged in secret an alliance where they promised to use their respective influence to support each other. The "triumvirate" was not a formal magistracy, nor did it achieve a lasting domination over state affairs.

Bona Dea was a goddess in ancient Roman religion. She was associated with chastity and fertility among married Roman women, healing, and the protection of the state and people of Rome. According to Roman literary sources, she was brought from Magna Graecia at some time during the early or middle Republic, and was given her own state cult on the Aventine Hill.

Saturnalia is an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through 19 December. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, and a public banquet, followed by private gift-giving, continual partying, and a carnival atmosphere that overturned Roman social norms: gambling was permitted, and masters provided table service for their slaves as it was seen as a time of liberty for both slaves and freedmen alike. A common custom was the election of a "King of the Saturnalia", who gave orders to people, which were followed and presided over the merrymaking. The gifts exchanged were usually gag gifts or small figurines made of wax or pottery known as sigillaria. The poet Catullus called it "the best of days".

The toga, a distinctive garment of ancient Rome, was a roughly semicircular cloth, between 12 and 20 feet in length, draped over the shoulders and around the body. It was usually woven from white wool, and was worn over a tunic. In Roman historical tradition, it is said to have been the favored dress of Romulus, Rome's founder; it was also thought to have originally been worn by both sexes, and by the citizen-military. As Roman women gradually adopted the stola, the toga was recognized as formal wear for male Roman citizens. Women found guilty of adultery and women engaged in prostitution might have provided the main exceptions to this rule.

Publius Clodius Pulcher was a populist Roman politician and street agitator during the time of the First Triumvirate. One of the most colourful personalities of his era, Clodius was descended from the aristocratic Claudia gens, one of Rome's oldest and noblest patrician families, but he contrived to be adopted by an obscure plebeian, so that he could be elected tribune of the plebs. During his term of office, he pushed through an ambitious legislative program, including a grain dole; but he is chiefly remembered for his long-running feuds with political opponents, particularly Cicero, whose writings offer antagonistic, detailed accounts and allegations concerning Clodius' political activities and scandalous lifestyle. Clodius was tried for the capital offence of sacrilege, following his intrusion on the women-only rites of the goddess Bona Dea, purportedly with the intention of seducing Caesar's wife Pompeia; his feud with Cicero led to Cicero's temporary exile; his feud with Milo ended in his own death at the hands of Milo's bodyguards.

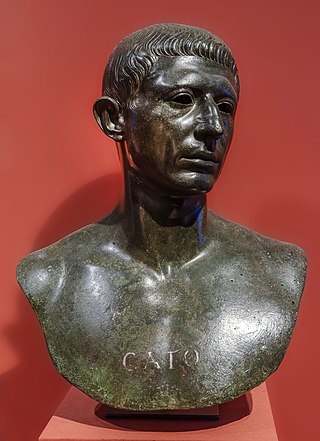

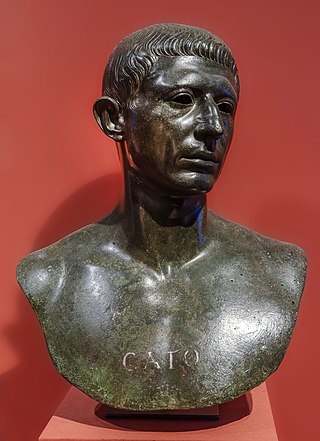

Marcus Porcius CatoUticensis, also known as Cato the Younger, was an influential conservative Roman senator during the late Republic. His conservative principles were focused on the preservation of what he saw as old Roman values in decline. A noted orator and a follower of Stoicism, his scrupulous honesty and professed respect for tradition gave him a powerful political following which he mobilised against powerful generals of his day.

The College of Pontiffs was a body of the ancient Roman state whose members were the highest-ranking priests of the state religion. The college consisted of the pontifex maximus and the other pontifices, the rex sacrorum, the fifteen flamens, and the Vestals. The College of Pontiffs was one of the four major priestly colleges; originally their responsibility was limited to supervising both public and private sacrifices, but as time passed their responsibilities increased. The other colleges were the augures, the quindecimviri sacris faciundis , and the epulones.

Gnaeus Flavius was the son of a freedman (libertinus) and rose to the office of aedile in the Roman Republic.

Ludi were public games held for the benefit and entertainment of the Roman people . Ludi were held in conjunction with, or sometimes as the major feature of, Roman religious festivals, and were also presented as part of the cult of state.

Leges Clodiae were a series of laws (plebiscites) passed by the Plebeian Council of the Roman Republic under the tribune Publius Clodius Pulcher in 58 BC. Clodius was a member of the patrician family ("gens") Claudius; the alternative spelling of his name is sometimes regarded as a political gesture. With the support of Julius Caesar, who held his first consulship in 59 BC, Clodius had himself adopted into a plebeian family in order to qualify for the office of tribune of the plebs, which was not open to patricians. Clodius was famously a bitter opponent of Cicero.

The gens Cloelia, originally Cluilia, and occasionally written Clouilia or Cloulia, was a patrician family at ancient Rome. The gens was prominent throughout the period of the Republic. The first of the Cloelii to hold the consulship was Quintus Cloelius Siculus, in 498 BC.

The gens Canidia was an obscure plebeian family at ancient Rome, first mentioned during the late Republic. It is best known from a single individual, Publius Canidius Crassus, consul suffectus in 40 BC, and the chief general of Marcus Antonius during the Perusine War. Other Canidii are known from inscriptions. The name Canidia was also used by Horace as a sobriquet for the perfumer, Gratidia.

The prosopography of ancient Rome is an approach to classical studies and ancient history that focuses on family connections, political alliances, and social networks in ancient Rome. The methodology of Roman prosopography involves defining a group for study—often the social ranking called ordo in Latin, as of senators and equestrians—then collecting and analyzing data. Literary sources provide evidence mainly for the ruling elite. Epigraphy and papyrology are sources that may also document ordinary people, who have been studied in groups such as imperial freedmen, lower-class families, and specific occupations such as wet nurses (nutrices).

The overthrow of the Roman monarchy was an event in ancient Rome that took place between the 6th and 5th centuries BC where a political revolution replaced the then-existing Roman monarchy under Lucius Tarquinius Superbus with a republic. The details of the event were largely forgotten by the Romans a few centuries later; later Roman historians invented a narrative of the events, traditionally dated to c. 509 BC, but this narrative is largely believed to be fictitious by modern scholars.

The gens Stertinia was a plebeian family of ancient Rome. It first rose to prominence at the time of the Second Punic War, and although none of its members attained the consulship in the time of the Republic, a number of Stertinii were so honoured in the course of the first two centuries of the Empire.

The gens Albinovana was an obscure plebeian family at ancient Rome. No members of this gens are known to have held any of the higher offices of the Roman state, and hardly any are mentioned in history. The family is perhaps best known from Publius Albinovanus, an infamous participant in the civil war between Marius and Sulla, and from the first-century poet Albinovanus Pedo. A number of Albinovani are known from inscriptions.