Risk society

Second modernity is marked by a new awareness of the risks — risks to all forms of life, plant, animal and human — created by the very successes of modernity in tackling the problem of human scarcity ( Carrier and Nordmann 2011 , 449). Systems that previously seemed to offer protection from risks both natural and social are increasingly recognised as producing new man-made risks on a global scale as a byproduct of their functioning ( He 2012 , 147). Such systems become part of the problem, not the solution. Modernisation and information advances themselves create new social dangers, such as cybercrime (He 2012, 69), while scientific advances open up new areas, like cloning or genetic modification, where decisions are necessarily made without adequate capacity to assess longterm consequences ( Allan, Adam, and Carter 1999 , xii–ii).

Recognising the fresh dilemmas created by this reflexive modernization, Beck has suggested a new "cosmopolitan Realpolitik" to overcome the difficulties of a world in which national interests can no longer be promoted effectively at the national level alone ( Beck 2006 , 173).

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissance—in the Age of Reason of 17th-century thought and the 18th-century Enlightenment. Some commentators consider the era of modernity to have ended by 1930, with World War II in 1945, or the 1980s or 1990s; the following era is called postmodernity. The term "contemporary history" is also used to refer to the post-1945 timeframe, without assigning it to either the modern or postmodern era.

Ulrich Beck was a German sociologist, and one of the most cited social scientists in the world during his lifetime. His work focused on questions of uncontrollability, ignorance and uncertainty in the modern age, and he coined the terms "risk society" and "second modernity" or "reflexive modernization". He also tried to overturn national perspectives that predominated in sociological investigations with a cosmopolitanism that acknowledges the interconnectedness of the modern world. He was a professor at the University of Munich and also held appointments at the Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme (FMSH) in Paris, and at the London School of Economics.

Ecological modernization is a school of thought that argues that both the state and the market can work together to protect the environment. It has gained increasing attention among scholars and policymakers in the last several decades internationally. It is an analytical approach as well as a policy strategy and environmental discourse.

Anthony Giddens, Baron Giddens is an English sociologist who is known for his theory of structuration and his holistic view of modern societies. He is considered to be one of the most prominent modern sociologists and is the author of at least 34 books, published in at least 29 languages, issuing on average more than one book every year. In 2007, Giddens was listed as the fifth most-referenced author of books in the humanities. He has academic appointments in approximately twenty different universities throughout the world and has received numerous honorary degrees.

Science studies is an interdisciplinary research area that seeks to situate scientific expertise in broad social, historical, and philosophical contexts. It uses various methods to analyze the production, representation and reception of scientific knowledge and its epistemic and semiotic role.

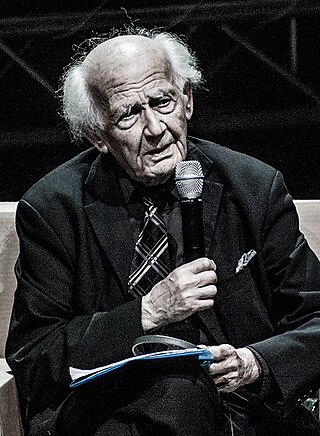

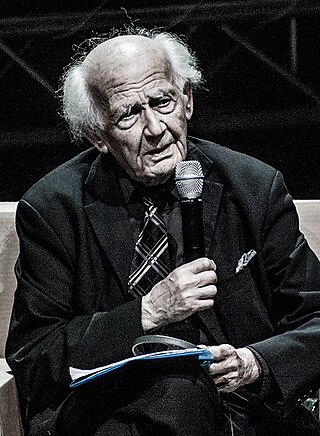

Zygmunt Bauman was a Polish-born sociologist and philosopher. He was driven out of the Polish People's Republic during the 1968 Polish political crisis and forced to give up his Polish citizenship. He emigrated to Israel; three years later he moved to the United Kingdom. He resided in England from 1971, where he studied at the London School of Economics and became Professor of Sociology at the University of Leeds, later Emeritus. Bauman was a social theorist, writing on issues as diverse as modernity and the Holocaust, postmodern consumerism and liquid modernity.

The sociology of scientific knowledge (SSK) is the study of science as a social activity, especially dealing with "the social conditions and effects of science, and with the social structures and processes of scientific activity." The sociology of scientific ignorance (SSI) is complementary to the sociology of scientific knowledge. For comparison, the sociology of knowledge studies the impact of human knowledge and the prevailing ideas on societies and relations between knowledge and the social context within which it arises.

Risk society is the manner in which modern society organizes in response to risk. The term is closely associated with several key writers on modernity, in particular Ulrich Beck and Anthony Giddens. The term was coined in the 1980s and its popularity during the 1990s was both as a consequence of its links to trends in thinking about wider modernity, and also to its links to popular discourse, in particular the growing environmental concerns during the period.

The concept of reflexive modernization or reflexive modernity was launched by a joint effort of three of the leading European sociologists: Anthony Giddens, Ulrich Beck and Scott Lash. The introduction of this concept served a double purpose: to reassess sociology as a science of the present, and to provide a counterbalance to the postmodernist paradigm offering a re-constructive view alongside deconstruction.

Social Risk Positions are social positions that are dictated by the ability to avert risk. They are largely dependent on an individual’s ability to access knowledge. Because manufactured risk is often imperceptible to the bare human senses, social risk position must be gained by creating networks of knowledge with other humans who have a greater access to risk information. Social risk positions influence status in risk society.

Claus Offe is a political sociologist of Marxist orientation. He received his PhD from the University of Frankfurt and his Habilitation at the University of Konstanz. In Germany, he has held chairs for Political Science and Political Sociology at the Universities of Bielefeld (1975–1989) and Bremen (1989–1995), as well as at the Humboldt-University of Berlin (1995–2005). He has worked as fellow and visiting professor at the Institutes for Advanced Study in Stanford, Princeton, and the Australian National University as well as Harvard University, the University of California at Berkeley and The New School University, New York. Once a student of Jürgen Habermas, the left-leaning German academic is counted among the second generation Frankfurt School. He currently teaches political sociology at a private university in Berlin, the Hertie School of Governance.

Reflectivism is an umbrella label used in International Relations theory for a range of theoretical approaches which oppose rational-choice accounts of social phenomena and positivism generally. The label was popularised by Robert Keohane in his presidential address to the International Studies Association in 1988. The address was entitled "International Institutions: Two Approaches", and contrasted two broad approaches to the study of international institutions. One was "rationalism", the other what Keohane referred to as "reflectivism". Rationalists — including realists, neo-realists, liberals, neo-liberals, and scholars using game-theoretic or expected-utility models — are theorists who adopt the broad theoretical and ontological commitments of rational-choice theory.

In epistemology, and more specifically, the sociology of knowledge, reflexivity refers to circular relationships between cause and effect, especially as embedded in human belief structures. A reflexive relationship is multi-directional when the causes and the effects affect the reflexive agent in a layered or complex sociological relationship. The complexity of this relationship can be furthered when epistemology includes religion.

Late modernity is the characterization of today's highly developed global societies as the continuation of modernity rather than as an element of the succeeding era known as postmodernity, or the postmodern. Introduced as "liquid" modernity by the Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, late modernity is marked by the global capitalist economies with their increasing privatization of services and by the information revolution. Among its characteristics is that some traits, which in previous generations were assigned to individuals by the community, are instead self-assigned individually and can be changed at will. As a result, people feel insecure about their identities and their places in society, and they feel anxious and distrustful about whether their self-proclaimed traits are being respected. Society as a whole feels more chaotic.

Scott Lash is a professor of sociology and cultural studies at Goldsmiths, University of London. Lash obtained a BSc in Psychology from the University of Michigan, an MA in Sociology from Northwestern University, and a PhD from the London School of Economics (1980). Lash began his teaching career as a lecturer at Lancaster University and became a professor in 1993. He moved to London in 1998 to take up his present post as Director for the Centre for Cultural Studies and Professor of Sociology at Goldsmiths College.

The following events related to sociology occurred in the 1980s.

The following events related to sociology occurred in the 1990s.

Brian Wynne is Professor Emeritus of Science Studies and a former Research Director of the Centre for the Study of Environmental Change (CSEC) at the Lancaster University. His education includes an MA, PhD, MPhil. His work has covered technology and risk assessment, public risk perceptions, and public understanding of science, focusing on the relations between expert and lay knowledge and policy decision-making.

Hilary Ann Rose is a British sociologist.

Han Sang-jin is a South Korean sociologist in the tradition of critical theory, known for his Joongmin theory. He is professor emeritus at the department of sociology, Seoul National University, Korea, and a distinguished visiting professor at Peking University, China. He has lectured as visiting professor at Columbia University in New York, United States, School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences in Paris, France, the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina, and Kyoto University in Japan. His major areas of interest are: social theory, political sociology, human rights and transitional justice, middle class politics, participatory risk governance, Confucianism and East Asian development.