Related Research Articles

In the United States, the relationship between race and crime has been a topic of public controversy and scholarly debate for more than a century. Crime rates vary significantly between racial groups; a 2005 study by the American Journal of Public Health observed that the odds of perpetrating violence were 85% higher for blacks compared with whites, with Latino-perpetrated violence 10% lower. However, academic research indicates that the over-representation of some racial minorities in the criminal justice system can in part be explained by socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, exposure to poor neighborhoods, poor access to public and early education, and exposure to harmful chemicals and pollution. Racial housing segregation has also been linked to racial disparities in crime rates, as blacks have historically and to the present been prevented from moving into prosperous low-crime areas through actions of the government and private actors. Various explanations within criminology have been proposed for racial disparities in crime rates, including conflict theory, strain theory, general strain theory, social disorganization theory, macrostructural opportunity theory, social control theory, and subcultural theory.

Sex differences in crime are differences between men and women as the perpetrators or victims of crime. Such studies may belong to fields such as criminology, sociobiology, or feminist studies. Despite the difficulty of interpreting them, crime statistics may provide a way to investigate such a relationship from a gender differences perspective. An observable difference in crime rates between men and women might be due to social and cultural factors, crimes going unreported, or to biological factors for example, testosterone or sociobiological theories). The nature of the crime itself may also require consideration as a factor.

Marxist criminology is one of the schools of criminology. It parallels the work of the structural functionalism school which focuses on what produces stability and continuity in society but, unlike the functionalists, it adopts a predefined political philosophy. As in conflict criminology, it focuses on why things change, identifying the disruptive forces in industrialized societies, and describing how society is divided by power, wealth, prestige, and the perceptions of the world. "The shape and character of the legal system in complex societies can be understood as deriving from the conflicts inherent in the structure of these societies which are stratified economically and politically". It is concerned with the causal relationships between society and crime, i.e. to establish a critical understanding of how the immediate and structural social environment gives rise to crime and criminogenic conditions.

Right realism, in criminology, also known as New Right Realism, Neo-Classicism, Neo-Positivism, or Neo-Conservatism, is the ideological polar opposite of left realism. It considers the phenomenon of crime from the perspective of political conservatism and asserts that it takes a more realistic view of the causes of crime and deviance, and identifies the best mechanisms for its control. Unlike the other schools of criminology, there is less emphasis on developing theories of causality in relation to crime and deviance. The school employs a rationalist, direct and scientific approach to policy-making for the prevention and control of crime. Some politicians who ascribe to the perspective may address aspects of crime policy in ideological terms by referring to freedom, justice, and responsibility. For example, they may be asserting that individual freedom should only be limited by a duty not to use force against others. This, however, does not reflect the genuine quality in the theoretical and academic work and the real contribution made to the nature of criminal behaviour by criminologists of the school.

In criminology, the Neo-Classical School continues the traditions of the Classical School within the framework of Right Realism. Hence, the utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham and Cesare Beccaria remains a relevant social philosophy in policy term for using punishment as a deterrent through law enforcement, the courts, and imprisonment.

In criminology, social control theory proposes that exploiting the process of socialization and social learning builds self-control and reduces the inclination to indulge in behavior recognized as antisocial. It derived from functionalist theories of crime and was developed by Ivan Nye (1958), who proposed that there were three types of control:

The Positivist School was founded by Cesare Lombroso and led by two others: Enrico Ferri and Raffaele Garofalo. In criminology, it has attempted to find scientific objectivity for the measurement and quantification of criminal behavior. Its method was developed by observing the characteristics of criminals to observe what may be the root cause of their behavior or actions. Since the Positivist's school of ideas came around, research revolving around its ideas has sought to identify some of the key differences between those who were deemed "criminals" and those who were not, often without considering flaws in the label of what a “criminal” is.

The feminist school of criminology is a school of criminology developed in the late 1960s and into the 1970s as a reaction to the general disregard and discrimination of women in the traditional study of crime. It is the view of the feminist school of criminology that a majority of criminological theories were developed through studies on male subjects and focused on male criminality, and that criminologists often would "add women and stir" rather than develop separate theories on female criminality.

In sociology and criminology, strain theory states that social structures within society may pressure citizens to commit crime. Following on the work of Émile Durkheim, strain theories have been advanced by Robert King Merton (1938), Albert K. Cohen (1955), Richard Cloward, Lloyd Ohlin (1960), Neil Smelser (1963), Robert Agnew (1992), Steven Messner, Richard Rosenfeld (1994) and Jie Zhang (2012).

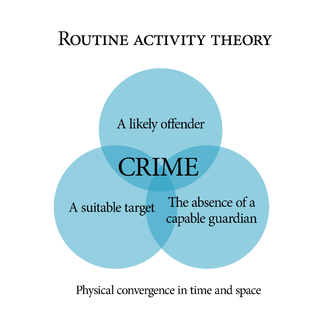

Routine activity theory is a sub-field of crime opportunity theory that focuses on situations of crimes. It was first proposed by Marcus Felson and Lawrence E. Cohen in their explanation of crime rate changes in the United States between 1947 and 1974. The theory has been extensively applied and has become one of the most cited theories in criminology. Unlike criminological theories of criminality, routine activity theory studies crime as an event, closely relates crime to its environment and emphasizes its ecological process, thereby diverting academic attention away from mere offenders.

Deviance or the sociology of deviance explores the actions and/or behaviors that violate social norms across formally enacted rules as well as informal violations of social norms. Although deviance may have a negative connotation, the violation of social norms is not always a negative action; positive deviation exists in some situations. Although a norm is violated, a behavior can still be classified as positive or acceptable.

Travis Warner Hirschi was an American sociologist and an emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Arizona. He helped to develop the modern version of the social control theory of crime and later the self-control theory of crime.

Biosocial criminology is an interdisciplinary field that aims to explain crime and antisocial behavior by exploring biocultural factors. While contemporary criminology has been dominated by sociological theories, biosocial criminology also recognizes the potential contributions of fields such as behavioral genetics, neuropsychology, and evolutionary psychology.

The correlates of crime explore the associations of specific non-criminal factors with specific crimes.

General strain theory (GST) is a theory of criminology developed by Robert Agnew. General strain theory has gained a significant amount of academic attention since being developed in 1992. Robert Agnew's general strain theory is considered to be a solid theory, has accumulated a significant amount of empirical evidence, and has also expanded its primary scope by offering explanations of phenomena outside of criminal behavior. This theory is presented as a micro-level theory because it focuses more on a single person at a time rather than looking at the whole of society.

Criminology is the interdisciplinary study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is a multidisciplinary field in both the behavioural and social sciences, which draws primarily upon the research of sociologists, political scientists, economists, legal sociologists, psychologists, philosophers, psychiatrists, social workers, biologists, social anthropologists, scholars of law and jurisprudence, as well as the processes that define administration of justice and the criminal justice system.

Crime displacement is the relocation of crime as a result of police crime-prevention efforts. Crime displacement has been linked to problem-oriented policing, but it may occur at other levels and for other reasons. Community-development efforts may be a reason why criminals move to other areas for their criminal activity. The idea behind displacement is that when motivated criminal offenders are deterred, they will commit crimes elsewhere. Geographic police initiatives include assigning police officers to specific districts so they become familiar with residents and their problems, creating a bond between law-enforcement agencies and the community. These initiatives complement crime displacement, and are a form of crime prevention. Experts in the area of crime displacement include Kate Bowers, Rob T. Guerette, and John E. Eck.

Criminal spin is a phenomenological model in criminology, depicting the development of criminal behavior. The model refers to those types of behavior that start out as something small and innocent, without malicious or criminal intent and as a result of one situation leading to the next, an almost inevitable chain of reactions triggering counter-reactions is set in motion, culminating in a spin of ever-intensifying criminal behavior. The criminal spin model was developed by Pro. Natti Ronel and his research team in the department of criminology at Bar-Ilan University. It was first presented in 2005 at a Bar-Ilan conference entitled “Appropriate Law Enforcement”.

Legal cynicism is a domain of legal socialization defined by a perception that the legal system and law enforcement agents are "illegitimate, unresponsive, and ill equipped to ensure public safety." It is related to police legitimacy, and the two serve as important ways for researchers to study citizens' perceptions of law enforcement.

Donald Arthur Andrews was a Canadian correctional psychologist and criminologist who taught at Carleton University, where he was a founding member of the Institute of Criminology and Criminal Justice. He is recognized for having criticized Robert Martinson's influential paper concluding that "nothing works" in correctional treatment. He also helped to advance the technique of risk assessment to better predict the chance of recidivism among offenders. He is credited with coining the terms "criminogenic needs" and "risk-need-responsivity", both of which have since been used and studied extensively in the criminological literature.

References

- 1 2 Muraven, Mark; Greg Pogarsky; Dikla Shmueli (June 2006). "Self-control Depletion and the General Theory of Crime". J Quant Criminol. 22 (3): 263–277. doi:10.1007/s10940-006-9011-1. S2CID 27357324.

- 1 2 Diksha, J., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- ↑ Hay, C. (2001). "Parenting, self-control, and delinquency: A test of self-control theory". Criminology. 39 (3): 707–734. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00938.x.

- 1 2 Pratt, Travis C.; Cullen, Francis T. (2000). "The empirical status of Gottfredssons and Hirschi's General Theory of Crime: A Meta analysis". Criminology. 38 (3): 931–964. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2000.tb00911.x. S2CID 143951341.

- ↑ Hirschi, T.; Gottfredson, M. R. (1983). "Age and the explanation of crime". American Journal of Sociology. 89 (3): 552–584. doi:10.1086/227905. S2CID 144647077.

- ↑ "Pleasure principle (psychology)", Wikipedia, 2020-02-29, retrieved 2020-04-03

- ↑ "Reality principle", Wikipedia, 2019-07-27, retrieved 2020-04-03

- ↑ Hasan Buker (2011). "Formation of self-control: Gottfredson and Hirschi's general theory of crime and beyond". 16 (3): 265–276.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Ronel, N. (2011). "Criminal behavior, criminal mind: Being caught in a criminal spin". International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55(8), 1208 - 1233.

- ↑ Porter, L. E., & Alison, L. J. (2006). "Examining group rape: A descriptive analysis of offender and victim behaviour." European Journal of Criminology, 3, 357-381.

- ↑ Fagan, J., Wilkinson, D. L., & Davies, G. (2007). "Social contagion of violence." In D. A. Flannery, A. T. Vazsonyi, & V. I. Waldman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression (pp. 668-726). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Akers, Ronald L. (1991). "Self-control as a general theory of crime". Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 7 (2): 201–211. doi:10.1007/BF01268629. S2CID 144549679.

- ↑

- LaGrange, T. C.; Silverman, R. A. (1999). "Low Self-control and Opportunity: Testing the General Theory of Crime as an Explanation for Gender Differences in Delinquency". Criminology. 37: 41–72. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1999.tb00479.x.

- ↑ Vazsonyi, A. T.; Belliston, L. M. (2007). "The Family → Low Self-Control → Deviance: A Cross-Cultural and Cross-National Test of Self-Control Theory". Criminal Justice and Behavior. 34 (4): 505–530. doi:10.1177/0093854806292299. S2CID 16139503.