Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthaginians and Romans, among others. Crucifixion has been used in parts of the world as recently as the 21st century.

The Iron Crown is a relic and may be one of the oldest royal insignia of Christendom. It was made in the Early Middle Ages, consisting of a circlet of gold and jewels fitted around a central silver band, which tradition held to be made of iron beaten out of a nail of the True Cross. In the medieval Kingdom of Italy, the crown came to be seen as a relic from the Kingdom of the Lombards and was used as regalia for the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperors as kings of Italy. It is kept in the Duomo of Monza.

Triclavianism is the belief that three nails were used to crucify Jesus Christ. The exact number of the Holy Nails has been a matter of speculation for centuries. The general modern understanding in the Catholic Church is that Christ was crucified with four nails, but three are sometimes depicted as a symbolic reference to the Holy Trinity.

Count Leopoldo Cicognara was an Italian artist, art collector, art historian and bibliophile.

The Order of the Iron Crown was an order of merit that was established on 5 June 1805 in the Kingdom of Italy by Napoleon Bonaparte under his title of Napoleon I, King of Italy.

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter is a work by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, painted in 1601 for the Cerasi Chapel of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. Across the chapel is a second Caravaggio work depicting the Conversion of Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus (1601). On the altar between the two is the Assumption of the Virgin Mary by Annibale Carracci.

The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew (1607) is a painting by the Italian Baroque master Caravaggio. It is in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, which acquired it from the Arnaiz collection in Madrid in 1976, having been taken to Spain by the Spanish Viceroy of Naples in 1610.

The raising of the Cross or elevation of the Cross has been a distinct subject in the Life of Christ in art depicting the start of the Crucifixion of Jesus.

Agnello Participazio was the tenth traditional and eighth (historical) doge of the Duchy of Venetia from 811 to 827. He was born to a rich merchant family from Heraclea and was one of the earliest settlers in the Rivoalto group of islands. His family had provided a number of tribuni militum of Rivoalto. He owned property near the Church of Santi Apostoli. A building in the nearby Campiello del Cason was the residence of the tribunes. Agnello was married to the dogaressa Elena.

Carlo Porta was an Italian poet, the most famous writer in Milanese.

Alessandro Marchesini was an Italian painter and art merchant of the late-Baroque and Rococo, active in Northern Italy and Venice. He first trained in Verona with Biagio Falcieri and then with Antonio Calza. He then moved to Bologna, to work in the studio of Carlo Cignani. He is described as gaining fame for his allegories with small figures. He painted in for the church of San Silvestro, Venice; and for the church of Santo Stefano, Verona. He is also remembered for recommending a young painter, Canaletto, to the Lucchese art collector Stefano Conti, stating that he was like Luca Carlevaris but with a sun shining. Among his pupils is Carlo Salis.

The Domini di Terraferma was the hinterland territories of the Republic of Venice beyond the Adriatic coast in Northeast Italy. They were one of the three subdivisions of the Republic's possessions, the other two being the original Dogado (Duchy) and the Stato da Màr.

Francesco Panigarola was an Italian Franciscan preacher and controversialist, and Bishop of Asti.

The crucifixion and death of Jesus occurred in 1st-century Judaea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, attested to by other ancient sources, and is considered an established historical event. There is no consensus among historians on the details.

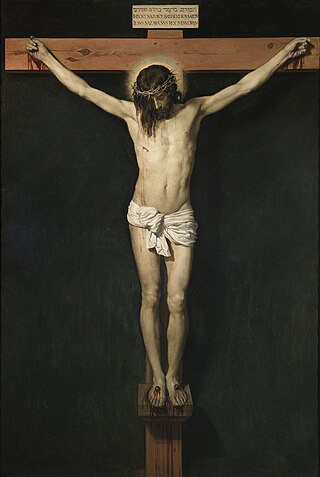

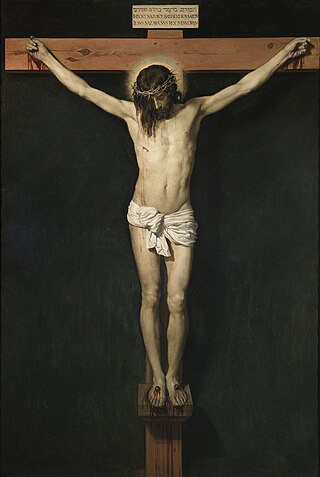

Crucifixions and crucifixes have appeared in the arts and popular culture from before the era of the pagan Roman Empire. The crucifixion of Jesus has been depicted in a wide range of religious art since the 4th century CE, much of which has included the appearance of mournful onlookers, the Virgin Mary, angels, Pontius Pilate and even antisemeitc depictions of deicidal Jews. In more modern times, crucifixion has appeared in film and television as well as in fine art, and depictions of other historical crucifixions have appeared as well as the crucifixion of Christ. Modern art and culture have also seen the rise of images of crucifixion being used to make statements unconnected with Christian iconography, or even just used for shock value.

Simone Stratigo was an Italian Greek mathematician and a nautical science expert who studied and lived in Padua and Pavia in 18th-century Italy.

Crucifixion in the Philippines is a devotional practice held every Good Friday, and is part of the local observance of Holy Week. Devotees or penitents called magdarame in Kapampangan are willingly pretend to crucified in imitation of Jesus Christ's suffering and death, while related practices include carrying wooden crosses, crawling on rough pavement, and self-flagellation. Penitents consider these acts to be mortification of the flesh, and undertake these to ask forgiveness for sins, to fulfil a panatà, or to express gratitude for favours granted. In the most famous case, Ruben Enaje drives four-inch nails into both hands and feet and then he is lifted on a wooden cross for around five minutes.

The Crucifixion with Pietà or Crucifixion is a painting by the Italian Renaissance painter Lorenzo Lotto, executed in 1529–1534 and housed in the church of Santa Maria della Pietà in Telusiano, Monte San Giusto, province of Macerata, region of Marche, Italy.

The Berlin Crucifixion is a tempera and gold on panel painting that was created c. 1320 and is attributed to Giotto. It is stored at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin.

Savino Monelli was an Italian tenor prominent in the opera houses of Italy from 1806 until 1830. Amongst the numerous roles he created in world premieres were Giannetto in Rossini's La gazza ladra, Enrico in Donizetti's L'ajo nell'imbarazzo and Nadir in Pacini's La schiava in Bagdad. He was born in Fermo where he initially studied music. After leaving the stage, he retired to Fermo and died there five years later at the age of 52.