Related Research Articles

The Iraq disarmament crisis was claimed as one of primary issues that led to the multinational invasion of Iraq on 20 March 2003.

The Charter of the United Nations (UN) is the foundational treaty of the United Nations. It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the Secretariat, the General Assembly, the Security Council, the Economic and Social Council, the International Court of Justice, and the Trusteeship Council.

The right of self-defense is the right for people to use reasonable or defensive force, for the purpose of defending one's own life (self-defense) or the lives of others, including, in certain circumstances, the use of deadly force.

The legitimacy under international law of the 1999 NATO bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia has been questioned. The UN Charter is the foundational legal document of the United Nations (UN) and is the cornerstone of the public international law governing the use of force between States. NATO members are also subject to the North Atlantic Treaty.

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act by an authorized party of a national government, in order to create a state of war between two or more states.

A preemptive war is a war that is commenced in an attempt to repel or defeat a perceived imminent offensive or invasion, or to gain a strategic advantage in an impending war shortly before that attack materializes. It is a war that preemptively 'breaks the peace' before an impending attack occurs.

Jus ad bellum, literally "right to war" in Latin, refers to "the conditions under which States may resort to war or to the use of armed force in general". This is distinct from the set of rules that ought to be followed during a war, known as jus in bello, which govern the behavior of parties in an armed conflict.

A preventive war is an armed conflict "initiated in the belief that military conflict, while not imminent, is inevitable, and that to delay would involve greater risk." The party which is being attacked has a latent threat capability or it has shown that it intends to attack in the future, based on its past actions and posturing. A preventive war aims to forestall a shift in the balance of power by strategically attacking before the balance of power has had a chance to shift in the favor of the targeted party. Preventive war is distinct from preemptive strike, which is the first strike when an attack is imminent. Preventive uses of force "seek to stop another state. .. from developing a military capability before it becomes threatening or to hobble or destroy it thereafter, whereas [p]reemptive uses of force come against a backdrop of tactical intelligence or warning indicating imminent military action by an adversary."

A war of aggression, sometimes also war of conquest, is a military conflict waged without the justification of self-defense, usually for territorial gain and subjugation, in contrast with the concept of a just war.

A defensive war is one of the causes that justify war by the criteria of the Just War tradition. It means a war where at least one nation is mainly trying to defend itself from another, as opposed to a war where both sides are trying to invade and conquer each other.

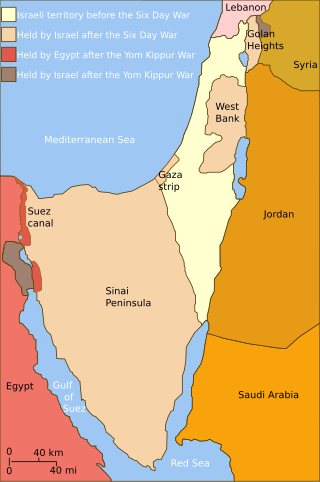

The International law bearing on issues of Arab–Israeli conflict, which became a major arena of regional and international tension since the birth of Israel in 1948, resulting in several disputes between a number of Arab countries and Israel.

The U.S. rationale for the Iraq War has faced heavy criticism from an array of popular and official sources both inside and outside the United States. Putting this controversy aside, both proponents and opponents of the invasion have also criticized the prosecution of the war effort along a number of lines. Most significantly, critics have assailed the U.S. and its allies for not devoting enough troops to the mission, not adequately planning for post-invasion Iraq, and for permitting and perpetrating widespread human rights abuses. As the war has progressed, critics have also railed against the high human and financial costs.

The use of force by states is controlled by both customary international law and by treaty law. The UN Charter reads in article 2(4):

All members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations.

Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter sets out the UN Security Council's powers to maintain peace. It allows the Council to "determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression" and to take military and nonmilitary action to "restore international peace and security".

United Nations Security Council Resolution 338 was a three-line resolution adopted by the UN Security Council on 22 October 1973, which called for a ceasefire in the Yom Kippur War in accordance with a joint proposal by the United States and the Soviet Union. It was passed at the 1747th Security Council meeting by 14 votes to none, with China abstaining.

The Security Treaty between the United States and Japan was a treaty signed on 8 September 1951 in San Francisco, California by representatives of the United States and Japan, in conjunction with the Treaty of San Francisco that ended World War II in Asia. The treaty was imposed on Japan by the United States as a condition for ending the Occupation of Japan and restoring Japan's sovereignty as a nation. It had the effect of establishing a long-lasting military alliance between the United States and Japan.

Chapter I of the United Nations Charter lays out the purposes and principles of the United Nations organization. These principles include the equality and self-determination of nations, respect of human rights and fundamental freedoms and the obligation of member countries to obey the Charter, to cooperate with the UN Security Council and to use peaceful means to resolve conflicts. These "purposes and principles" reflect a premise that the effectiveness of the United Nations would be enhanced with broad guidelines to guide the actions of its Organisations and member states. However, some members were concerned that these proposals granted what they considered overly broad discretionary powers for the organs of the United Nations in the Dumbarton Oaks Conference proposals. And the adopted purposes and principles have been seen as reflecting the compromise achieved.

The Caroline test is a 19th-century formulation of customary international law, reaffirmed by the Nuremberg Tribunal after World War II, which said that the necessity for preemptive self-defense must be "instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation." The test takes its name from the Caroline affair.

Schmitt analysis is a legal framework developed in 1999 by Michael N. Schmitt, leading author of the Tallinn Manual, for deciding if a state's involvement in a cyber-attack constitutes a use of force. Such a framework is important as part of international law's adaptation process to the growing threat of cyber-warfare. The characteristics of a cyber-attack can determine which legal regime will govern state behavior, and the Schmitt analysis is one of the most commonly used ways of analyzing those characteristics. It can also be used as a basis for training professionals in the legal field to deal with cyberwarfare.

References

- Sources

- Ben Fritz, "Sorting out the "imminent threat" debate,", spinsanity.org, November 3, 2003

- Dan Darling, "Special Analysis: The Imminent Threat," windsofchange.net, September 4, 2003

- Wolf Schäfer, "Learning From Recent History," Provost’s Lecture Series on Global Issues - The People Speak: America Debates its Role in the World, Stony Brook University, October 15, 2003

- Michael Byers, "Jumping the Gun", London Review of Books, Vol. 24 No. 14, 25 July 2002, pp 3–5

- Matthew Omolesky, "Special Report: Israel and International Law," The American Spectator , 7.18.06

- The Caroline Case : Anticipatory Self-Defence in Contemporary International Law

- The Caroline Incident during the Patriot War

- Obituary of Neil MacGregor, one of the Upper Canada militiamen on the raid

- The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: The Webster-Ashburton Treaty and The Caroline Case

- Chapter 7, "British Steamer is Burned by Patriots" in Northern New York In The Patriot War, 1923, By L. N. Fuller

- The Caroline (Christopher Greenwood) in the context of international law - Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

- Notes

- ↑ Randelzhofer, Article 2(4) inThe Charter of the United Nations: A Commentary (1994).

- ↑ Kearley, Regulation of Preventive and Preemptive Force in the United Nations Charter: A Search for Original Intent,Wyoming Law Review, vol. 3, p. 663 (2003).

- ↑ Chapter VII, Article 51 of the UN Charter

- ↑ Randelzhofer, Article 2(4) inThe Charter of the United Nations: A Commentary (1994).

- ↑ Meng, The Caroline inEncyclopedia of Public International Law, vol. 1, p.538, and Bowett, Self-Defense in International Law, p.59 (1958).

- ↑ (Dan Webster, Yale Law School)

- ↑ Kearley, Raising the "Caroline"Wisconsin International Law Journal vol.17, p.325 (1994).