Sexual assault is an act in which one intentionally sexually touches another person without that person's consent, or coerces or physically forces a person to engage in a sexual act against their will. It is a form of sexual violence that includes child sexual abuse, groping, rape, drug facilitated sexual assault, and the torture of the person in a sexual manner.

Some victims of rape or other sexual violence incidents are male. It is estimated that approximately one in six men experienced sexual abuse during childhood. Historically, rape was thought to be, and defined as, a crime committed solely against females. This belief is still held in some parts of the world, but rape of males is now commonly criminalized and has been subject to more discussion than in the past.

The precise definitions of and punishments for aggravated sexual assault and aggravated rape vary by country and by legislature within a country.

The legal age of consent for sexual activity varies by jurisdiction across Asia. The specific activity engaged in or the gender of participants can also be relevant factors. Below is a discussion of the various laws dealing with this subject. The highlighted age refers to an age at or above which an individual can engage in unfettered sexual relations with another who is also at or above that age. Other variables, such as homosexual relations or close in age exceptions, may exist, and are noted when relevant.

The ages of consent vary by jurisdiction across Europe. The ages of consent – hereby meaning the age from which one is deemed able to consent to having sex with anyone else of consenting age or above – are between 14 and 18. The vast majority of countries set their ages in the range of 14 to 16; only four countries, Cyprus (17), Ireland (17), Turkey (18), and the Vatican City (18), set an age of consent higher than 16.

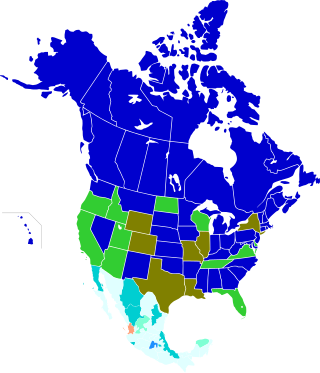

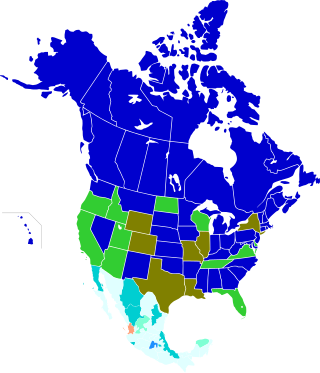

In North America, the legal age of consent relating to sexual activity varies by jurisdiction.

The age of consent in Africa for sexual activity varies by jurisdiction across the continent, codified in laws which may also stipulate the specific activities that are permitted or the gender of participants for different ages. Other variables may exist, such as close-in-age exemptions.

Rape is a type of sexual assault initiated by one or more persons against another person without that person's consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, under threat or manipulation, by impersonation, or with a person who is incapable of giving valid consent.

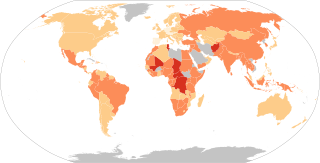

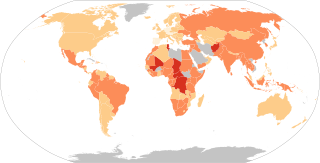

Statistics on rape and other acts of sexual assault are commonly available in industrialized countries, and have become better documented throughout the world. Inconsistent definitions of rape, different rates of reporting, recording, prosecution and conviction for rape can create controversial statistical disparities, and lead to accusations that many rape statistics are unreliable or misleading.

Rape is a type of sexual assault involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or against a person who is incapable of giving valid consent, such as one who is unconscious, incapacitated, has an intellectual disability, or is below the legal age of consent. The term rape is sometimes used interchangeably with the term sexual assault.

Laws regarding incest vary considerably between jurisdictions, and depend on the type of sexual activity and the nature of the family relationship of the parties involved, as well as the age and sex of the parties. Besides legal prohibitions, at least some forms of incest are also socially taboo or frowned upon in most cultures around the world.

Laws against child sexual abuse vary by country based on the local definition of who a child is and what constitutes child sexual abuse. Most countries in the world employ some form of age of consent, with sexual contact with an underage person being criminally penalized. As the age of consent to sexual behaviour varies from country to country, so too do definitions of child sexual abuse. An adult's sexual intercourse with a minor below the legal age of consent may sometimes be referred to as statutory rape, based on the principle that any apparent consent by a minor could not be considered legal consent.

In common law jurisdictions, statutory rape is nonforcible sexual activity in which one of the individuals is below the age of consent. Although it usually refers to adults engaging in sexual contact with minors under the age of consent, it is a generic term, and very few jurisdictions use the actual term statutory rape in the language of statutes. In statutory rape, overt force or threat is usually not present. Statutory rape laws presume coercion because a minor or mentally disabled adult is legally incapable of giving consent to the act.

In the United States, each state and territory sets the age of consent either by statute or the common law applies, and there are several federal statutes related to protecting minors from sexual predators. Depending on the jurisdiction, the legal age of consent is between 16 and 18. In some places, civil and criminal laws within the same state conflict with each other.

The Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009 is an Act of the Scottish Parliament. It creates a code of sexual offences that is said to be intended to reform that area of the law. The corresponding legislation in England and Wales is the Sexual Offences Act 2003 and in Northern Ireland the Sexual Offences Order 2008.

Rape is the fourth most common crime against women in India. According to the 2021 annual report of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), 31,677 rape cases were registered across the country, or an average of 86 cases daily, a rise from 2020 with 28,046 cases, while in 2019, 32,033 cases were registered. Of the total 31,677 rape cases, 28,147 of the rapes were committed by persons known to the victim. The share of victims who were minors or below 18 – the legal age of consent – stood at 10%.

Marital rape is illegal in all 50 US states, though the details of the offence vary by state.

Non-consensual condom removal, or "stealthing", is the practice of a person removing a condom during sexual intercourse without consent, when their sex partner has only consented to condom-protected sex. Purposefully damaging a condom before or during intercourse may also be referred to as stealthing, regardless of who damaged the condom.

Rape in Alabama is currently defined across three sections of its Criminal Code: Definitions, Rape in the First Degree, and Rape in the Second Degree. Each section addresses components of the crime such as age, sentencing, the genders of the individuals involved, and the acts involved.

Rape laws vary across the United States jurisdictions. However, rape is federally defined for statistical purposes as:

Penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim.