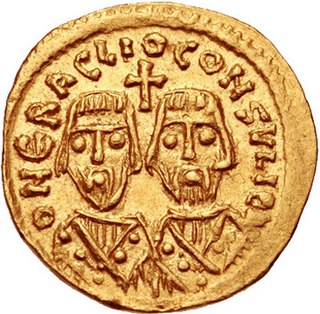

Heraclius was Byzantine emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the Exarch of Africa, led a revolt against the unpopular emperor Phocas.

The 620s decade ran from January 1, 620, to December 31, 629.

The 610s decade ran from January 1, 610, to December 31, 619.

Year 626 (DCXXVI) was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 626 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Shahrbaraz, was shah (king) of the Sasanian Empire from 27 April 630 to 9 June 630. He usurped the throne from Ardashir III, and was killed by Iranian nobles after forty days. Before usurping the Sasanian throne he was a spahbed (general) under Khosrow II (590–628). He is furthermore noted for his important role during the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, and the events that followed afterwards.

The Roman–Persian Wars, also known as the Roman–Iranian Wars, were a series of conflicts between states of the Greco-Roman world and two successive Iranian empires: the Parthian and the Sasanian. Battles between the Parthian Empire and the Roman Republic began in 54 BC; wars began under the late Republic, and continued through the Roman and Sasanian empires. A plethora of vassal kingdoms and allied nomadic nations in the form of buffer states and proxies also played a role. The wars were ended by the early Muslim conquests, which led to the fall of the Sasanian Empire and huge territorial losses for the Byzantine Empire, shortly after the end of the last war between them.

Heraclius' campaign of 622, erroneously also known as the Battle of Issus, was a major campaign in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 by emperor Heraclius that culminated in a crushing Byzantine victory in Anatolia.

Heraclius the Elder was a Byzantine general and the father of Byzantine emperor Heraclius. Generally considered to be of Armenian origin, Heraclius the Elder distinguished himself in the war against the Sassanid Persians in the 580s. As a subordinate general, Heraclius served under the command of Philippicus during the Battle of Solachon and possibly served under Comentiolus during the Battle of Sisarbanon. Circa 595, Heraclius the Elder is mentioned as a magister militum per Armeniam sent by Emperor Maurice to quell an Armenian rebellion led by Samuel Vahewuni and Atat Khorkhoruni. Circa 600, he was appointed as the Exarch of Africa and in 608, he rebelled with his son against the usurper Phocas. Using North Africa as a base, the younger Heraclius managed to overthrow Phocas, beginning the Heraclian dynasty, which would rule Byzantium for a century. Heraclius the Elder died soon after receiving news of his son's accession to the Byzantine throne.

Shahen or Shahin was a senior Sasanian general (spahbed) during the reign of Khosrow II (590–628). He was a member of the House of Spandiyadh.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the dynasty of Heraclius between 610 and 711. The Heraclians presided over a period of cataclysmic events that were a watershed in the history of the Empire and the world. Heraclius, the founder of his dynasty, was of Armenian and Cappadocian (Greek) origin. At the beginning of the dynasty, the Empire's culture was still essentially Ancient Roman, dominating the Mediterranean and harbouring a prosperous Late Antique urban civilization. This world was shattered by successive invasions, which resulted in extensive territorial losses, financial collapse and plagues that depopulated the cities, while religious controversies and rebellions further weakened the Empire.

Philippicus or Philippikos was an Eastern Roman general, comes excubitorum, and brother-in-law of Emperor Maurice. His successful career as a general spanned three decades, chiefly against the Sassanid Persians.

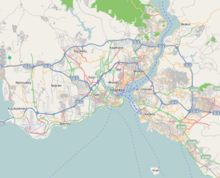

Bonus was a Byzantine statesman and general, one of the closest associates of Emperor Heraclius, who played a leading role in the successful defense of the imperial capital, Constantinople, during the Avar–Persian siege of 626.

The Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 was the final and most devastating of the series of wars fought between the Byzantine Empire and the Persian Sasanian Empire. The previous war between the two powers had ended in 591 after Emperor Maurice helped the Sasanian king Khosrow II regain his throne. In 602 Maurice was murdered by his political rival Phocas. Khosrow declared war, ostensibly to avenge the death of the deposed emperor Maurice. This became a decades-long conflict, the longest war in the series, and was fought throughout the Middle East: in Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus, Anatolia, Armenia, the Aegean Sea and before the walls of Constantinople itself.

Priscus or Priskos was a leading Eastern Roman general during the reigns of the Byzantine emperors Maurice, Phocas and Heraclius. Priscus comes across as an effective and capable military leader, although the contemporary sources are markedly biased in his favour. Under Maurice, he distinguished himself in the campaigns against the Avars and their Slavic allies in the Balkans. Absent from the capital at the time of Maurice's overthrow and murder by Phocas, he was one of the few of Maurice's senior aides who were able to survive unharmed into the new regime, remaining in high office and even marrying the new emperor's daughter. Priscus, however, also negotiated with and assisted Heraclius in the overthrow of Phocas, and was entrusted with command against the Persians in 611–612. After the failure of this campaign, he was dismissed and tonsured. He died shortly after.

Kardarigan was a Sassanid Persian general of the early 7th century, who fought in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. He is usually distinguished from another Persian general of the same name who was active during the 580s. The name is actually an honorific title and means "black hawk".

Shahraplakan, rendered Sarablangas (Σαραβλαγγᾶς) in Greek sources, was a Sassanid Persian general (spahbed) who participated in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 and the Third Perso-Turkic War.

Domentziolus or Domnitziolus was a nephew of the Byzantine emperor Phocas, appointed curopalates and general in the East during his uncle's reign. He was one of the senior Byzantine military leaders during the opening stages of the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628. His defeats opened the way for the fall of Mesopotamia and Armenia and the invasion of Anatolia by the Persians. In 610, Phocas was overthrown by Heraclius, and Domentziolus was captured but escaped serious harm.

Theodore was the brother of the Byzantine emperor Heraclius, a curopalates and leading general in Heraclius' wars against the Persians and against the Muslim conquest of the Levant.

Theodosius was the eldest son of Byzantine emperor Maurice and was co-emperor from 590 until his deposition and execution during a military revolt. Along with his father-in-law Germanus, he was briefly proposed as successor to Maurice by the troops, but the army eventually favoured Phocas instead. Sent in an abortive mission to secure aid from Sassanid Persia by his father, Theodosius was captured and executed by Phocas's supporters a few days after Maurice. Nevertheless, rumours spread that he had survived the execution, and became popular to the extent that a man who purported to be Theodosius was entertained by the Persians as a pretext for launching a war against Byzantium.

The Avar–Byzantine wars were a series of conflicts between the Byzantine Empire and the Avar Khaganate. The conflicts were initiated in 568, after the Avars arrived in Pannonia, and claimed all the former land of the Gepids and Lombards as their own. This led to an unsuccessful attempt to seize the city of Sirmium from Byzantium, which had previously retaken it from the Gepids. Most subsequent conflicts came as a result of raids by the Avars, or their subject Slavs, into the Balkan provinces of the Byzantine Empire.