Apollo is one of the Olympian deities in classical Greek and Roman religion and Greek and Roman mythology. The national divinity of the Greeks, Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, music and dance, truth and prophecy, healing and diseases, the Sun and light, poetry, and more. One of the most important and complex of the Greek gods, he is the son of Zeus and Leto, and the twin brother of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. Seen as the most beautiful god and the ideal of the kouros, Apollo is considered to be the most Greek of all the gods. Apollo is known in Greek-influenced Etruscan mythology as Apulu.

In ancient Greek religion, Hera is the goddess of marriage, women and family, and the protector of women during childbirth. In Greek mythology, she is queen of the twelve Olympians and Mount Olympus, sister and wife of Zeus, and daughter of the Titans Cronus and Rhea. One of her defining characteristics in myth is her jealous and vengeful nature in dealing with any who offend her, especially Zeus' numerous adulterous lovers and illegitimate offspring.

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Leto is a goddess and the mother of Apollo, the god of music, and Artemis, the goddess of the hunt. She is the daughter of the Titans Coeus and Phoebe, and the sister of Asteria.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Hestia is the virgin goddess of the hearth, the right ordering of domesticity, the family, the home, and the state. In myth, she is the firstborn child of the Titans Cronus and Rhea, and one of the Twelve Olympians.

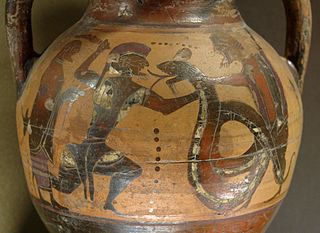

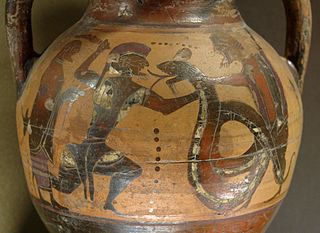

In Greek and Roman mythology, the Giants, also called Gigantes, were a race of great strength and aggression, though not necessarily of great size. They were known for the Gigantomachy, their battle with the Olympian gods. According to Hesiod, the Giants were the offspring of Gaia (Earth), born from the blood that fell when Uranus (Sky) was castrated by his Titan son Cronus.

In Greek mythology, an Amazonomachy is a mythological battle between the ancient Greeks and the Amazons, a nation of all-female warriors. The subject of Amazonomachies was popular in ancient Greek art and Roman art.

In Greek mythology, Porphyrion was one of the Gigantes (Giants), who according to Hesiod, were the offspring of Gaia, born from the blood that fell when Uranus (Sky) was castrated by their son Cronus. In some other versions of the myth, the Gigantes were born of Gaia and Tartarus.

Hebe, in ancient Greek religion and mythology, often given the ephitet Ganymeda , is the goddess of youth or the prime of life. She was the cupbearer for the gods and goddesses of Mount Olympus, serving their nectar and ambrosia. She also was worshipped as the goddess of forgiveness or mercy at Sicyon.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the twelve Olympians are the major deities of the Greek pantheon, commonly considered to be Zeus, Poseidon, Hera, Demeter, Aphrodite, Athena, Artemis, Apollo, Ares, Hephaestus, Hermes, and either Hestia or Dionysus. They were called Olympians because, according to tradition, they resided on Mount Olympus.

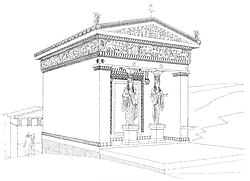

Greek temples were structures built to house deity statues within Greek sanctuaries in ancient Greek religion. The temple interiors did not serve as meeting places, since the sacrifices and rituals dedicated to the respective ouranic deity took place outside them, within the wider precinct of the sanctuary, which might be large. Temples were frequently used to store votive offerings. They are the most important and most widespread building type in Greek architecture. In the Hellenistic kingdoms of Southwest Asia and of North Africa, buildings erected to fulfill the functions of a temple often continued to follow the local traditions. Even where a Greek influence is visible, such structures are not normally considered as Greek temples. This applies, for example, to the Graeco-Parthian and Bactrian temples, or to the Ptolemaic examples, which follow Egyptian tradition. Most Greek temples were oriented astronomically.

The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. Modern scholarship identifies three major stages in monumental sculpture in bronze and stone: the Archaic, Classical (480–323) and Hellenistic. At all periods there were great numbers of Greek terracotta figurines and small sculptures in metal and other materials.

The metopes of the Parthenon are the surviving set of what were originally 92 square carved plaques of Pentelic marble originally located above the columns of the Parthenon peristyle on the Acropolis of Athens. If they were made by several artists, the master builder was certainly Phidias. They were carved between 447 or 446 BC. or at the latest 438 BC, with 442 BC as the probable date of completion. Most of them are very damaged. Typically, they represent two characters per metope either in action or repose.

The Temple of Aphaia or Afea is located within a sanctuary complex dedicated to the goddess Aphaia on the Greek island of Aigina, which lies in the Saronic Gulf. Formerly known as the Temple of Jupiter Panhellenius, the great Doric temple is now recognized as dedicated to the mother-goddess Aphaia. It was a favourite of the Neoclassical and Romantic artists such as J. M. W. Turner. It stands on a c. 160 m peak on the eastern side of the island approximately 13 km east by road from the main port.

Delphi Archaeological museum is one of the principal museums of Greece and one of the most visited. It is operated by the Greek Ministry of Culture. Founded in 1903, it has been rearranged several times and houses the discoveries made at the Panhellenic sanctuary of Delphi, which date from the Late Helladic (Mycenean) period to the early Byzantine era.

In Greek mythology, Mimas was one of the Gigantes (Giants), the offspring of Gaia, born from the blood of the castrated Uranus.

The Athenian Treasury at Delphi was constructed by the Athenians to house dedications and votive offerings made by their city and citizens to the sanctuary of Apollo. The entire treasury including its sculptural decoration is built of Parian marble. The date of construction is disputed, and scholarly opinions range from 510 to 480 BCE. It is located directly below the Temple of Apollo along the Sacred Way for all visitors to view the Athenian treasury on the way up to the sanctuary.

The gigantomachy by the Suessula Painter is a painting on a red-figure amphora from the Classical period of Greece. It is the work of the Suessula Painter, an Athenian vase-painter whose name is unknown. He worked in both Corinth and Athens and is recognizable by his style, with great freedom of posture and a unique shading of figures. Created around 410–400 BCE, this notable example of red-figure pottery stands 69.5 cm tall, 32 cm wide.

The pediments of the Parthenon are the two sets of statues in Pentelic marble originally located as the pedimental sculpture on the east and west facades of the Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens. They were probably made by several artists, including Agoracritos. The master builder was probably Phidias. They were probably lifted into place by 432 BC, having been carved on the ground.

In Greek mythology, Asterius is a Giant, the children of the deities Gaia and Uranus who fought and was killed by the goddess Athena.