The Site of the John and Mary Jones House is a site in Chicago, Illinois, in the United States that was designated as a Chicago Landmark on May 26, 2004. [1]

The Site of the John and Mary Jones House is a site in Chicago, Illinois, in the United States that was designated as a Chicago Landmark on May 26, 2004. [1]

John Jones and his wife Mary Jones were central figures of the abolitionist movement in Chicago, led early struggles to achieve civil rights for Blacks and were involved in local and state politics (including John Jones having been the first African-American to hold elected office in Illinois as a member of the Cook County Board of Commissioners.) [2]

They lived at 218 Edina Place (later Plymouth Court, and now corresponding approximately to 946 South Plymouth Court / 947 South Park Terrace) from 1857 to 1872. [2]

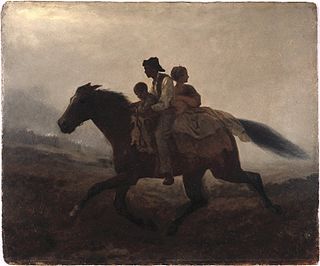

The home served as a "station" on the Underground Railroad, which helped hundreds of fugitive slaves find freedom in the North and Canada. Serving as "conductors" on the Underground Railroad, the Joneses provided food and shelter to fugitive slaves, as well as clothing, money for transportation, and often bail and bond. According to Jones' daughter Lavinia, John and Mary Jones were responsible for sending hundreds of fugitives to Canada throughout the 1850s and early 1860s. [2]

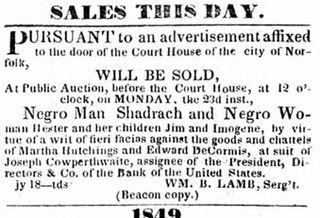

Although the Joneses were both born free and had freedom papers, they put themselves at great risk through their involvement with the Underground Railroad. Under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, harboring or preventing the arrest of a fugitive slave was punishable by a $500 fine and possible enslavement for free blacks. Further, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 led to manhunts by mercenary slave catchers, many of whom were not beyond capturing and putting into slavery free blacks that had never been slaves. [2]

Their Chicago residence also served as a meeting place for locally and nationally prominent abolitionists, including Allan Pinkerton, Frederick Douglass and John Brown, [3] : 132 and was the center of their life-long efforts to achieve greater civil rights for enslaved and free blacks alike. [2]

It is not known exactly when the house was demolished, but by 1883 its location had become part of the Dearborn Street Station railroad yards, constructed that year. [2] More recently, after the removal of the tracks in the late-1970s, the grounds of the house were incorporated into the then-newly developed Dearborn Park neighborhood of Chicago's near south side. Today, at the corner of 9th Street and Plymouth Court, there is no plaque or any other form of marker to commemorate the historic Jones house.

The Underground Railroad was a network of secret routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and from there to Canada. The network, primarily the work of free African Americans, was assisted by abolitionists and others sympathetic to the cause of the escapees. The slaves who risked capture and those who aided them are also collectively referred to as the passengers and conductors of the Railroad, respectively. Various other routes led to Mexico, where slavery had been abolished, and to islands in the Caribbean that were not part of the slave trade. An earlier escape route running south toward Florida, then a Spanish possession, existed from the late 17th century until approximately 1790. However, the network generally known as the Underground Railroad began in the late 18th century. It ran north and grew steadily until the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln. One estimate suggests that, by 1850, approximately 100,000 slaves had escaped to freedom via the network.

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was a law passed by the 31st United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Pearl incident was the largest recorded nonviolent escape attempt by enslaved people in United States history. On April 15, 1848, seventy-seven slaves attempted to escape Washington D.C. by sailing away on a schooner called The Pearl. Their plan was to sail south on the Potomac River, then north up the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware River to the free state of New Jersey, a distance of nearly 225 miles (362 km). The attempt was organized by both abolitionist whites and free blacks, who expanded the plan to include many more enslaved people. Paul Jennings, a former slave who had served President James Madison, helped plan the escape.

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freedom seekers to avoid implying that the enslaved person had committed a crime and that the slaveholder was the injured party.

Thomas Garrett was an American abolitionist and leader in the Underground Railroad movement before the American Civil War. He helped more than 2,500 African Americans escape slavery.

Shadrach Minkins was an African-American fugitive slave from Virginia who escaped in 1850 and reached Boston. He also used the pseudonyms Frederick Wilkins and Frederick Jenkins. He is known for being freed from a courtroom in Boston after being captured by United States marshals under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Members of the Boston Vigilance Committee freed and hid him, helping him get to Canada via the Underground Railroad. Minkins settled in Montreal, where he raised a family. Two men were prosecuted in Boston for helping free him, but they were acquitted by the jury.

Mary Edmonson (1832–1853) and Emily Edmonson, "two respectable young women of light complexion", were African Americans who became celebrities in the United States abolitionist movement after gaining their freedom from slavery. On April 15, 1848, they were among the 77 slaves who tried to escape from Washington, DC on the schooner The Pearl to sail up the Chesapeake Bay to freedom in New Jersey.

The pre-American Civil War practice of kidnapping into slavery in the United States occurred in both free and slave states, and both fugitive slaves and free negroes were transported to slave markets and sold, often multiple times. There were also rewards for the return of fugitives. Three types of kidnapping methods were employed: physical abduction, inveiglement of free blacks, and apprehension of fugitives. The enslavement, or re-enslavement, of free blacks occurred for 85 years, from 1780 to 1865.

The Underground Railroad in Indiana was part of a larger, unofficial, and loosely-connected network of groups and individuals who aided and facilitated the escape of runaway slaves from the southern United States. The network in Indiana gradually evolved in the 1830s and 1840s, reached its peak during the 1850s, and continued until slavery was abolished throughout the United States at the end of the American Civil War in 1865. It is not known how many fugitive slaves escaped through Indiana on their journey to Michigan and Canada. An unknown number of Indiana's abolitionists, anti-slavery advocates, and people of color, as well as Quakers and other religious groups illegally operated stations along the network. Some of the network's operatives have been identified, including Levi Coffin, the best-known of Indiana's Underground Railroad leaders. In addition to shelter, network agents provided food, guidance, and, in some cases, transportation to aid the runaways.

William Parker was an American former slave who escaped from Maryland to Pennsylvania, where he became an abolitionist and anti-slavery activist in Christiana. He was a farmer and led a black self-defense organization. He was notable as a principal figure in the Christiana incident, 1851, also known as the Christiana Resistance. Edward Gorsuch, a Maryland slaveowner who owned four slaves who had fled over the state border to Parker's farm, was killed and other white men in the party to capture the fugitives were wounded. The events brought national attention to the challenges of enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

The Hovenden House, Barn and Abolition Hall is a group of historic buildings which are located in Plymouth Meeting, Whitemarsh Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. In the decades prior to the American Civil War, this property served as an important station on the Underground Railroad. Abolition Hall was built to be a meeting place for abolitionists, and later was the studio of artist Thomas Hovenden.

Anna Maria Weems, also Ann Maria Weems, whose aliases included "Ellen Capron" and "Joe Wright," was an American woman known for escaping slavery by disguising herself as a male carriage driver and escaping to British North America, where her family was settled with other slave fugitives.

John Jones was an American abolitionist, businessman, civil rights leader, and philanthropist. He was born in North Carolina and later lived in Tennessee. Arriving in Chicago with three dollars in assets in 1845, Jones rose to become a leading African-American figure in the early history of Chicago.

Mary Jane Richardson Jones was an American abolitionist, philanthropist, and suffragist. Born in Tennessee to free black parents, Jones and her family moved to Illinois. With her husband, John, she was a leading African-American figure in the early history of Chicago. The Jones household was a stop on the Underground Railroad and a center of abolitionist activity in the pre-Civil War era, helping hundreds of fugitive slaves flee slavery.

The Underground Railroad in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania was a critical hub of the American Underground Railroad network, which helped men, women and children to escape the system of chattel slavery that existed in the United States during the nineteenth century.

Elijah Anderson was a free Black man and leading conductor of the Underground Railroad (UGRR). According to other abolitionist such as Rush R. Sloane, Anderson assisted at least 1,000 slaves to gain freedom.

Kentucky raid in Cass County (1847) was conducted by slaveholders and slave catchers who raided Underground Railroad stations in Cass County, Michigan to capture black people and return them to slavery. After unsuccessful attempts, and a lost court case, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was enacted. Michigan's Personal Liberty Act of 1855 was passed in the state legislature to prevent the capture of formerly enslaved people that would return them to slavery.

Wright Modlin or Wright Maudlin (1797–1866) helped enslaved people escape slavery, whether transporting them between Underground Railroad stations or traveling south to find people that he could deliver directly to Michigan. Modlin and his Underground Railroad partner, William Holden Jones, traveled to the Ohio River and into Kentucky to assist enslave people on their journey north. Due to their success, angry slaveholders instigated the Kentucky raid on Cass County of 1847. Two years later, he helped free his neighbors, the David and Lucy Powell family, who had been captured by their former slaveholder. Tried in South Bend, Indiana, the case was called The South Bend Fugitive Slave Case.

Dearborn Park is a residential Chicago neighborhood located in the Loop and Near South Side community areas of Chicago in Cook County, Illinois, United States. The area is known for its unique architecture, green spaces, and proximity to the city's downtown area and many cultural and recreational attractions. Early in Chicago history, this became an immigrant neighborhood before being ravaged by a fire in the 1870s, it was then bought up for railroad rights-of-way leading to Dearborn Station. When several rail-lines ceased service in the early 1970s, the trackage yards were themselves replaced and redeveloped into this neighborhood.