Related Research Articles

Witchcraft, as most commonly understood in both historical and present-day communities, is the use of alleged supernatural powers of magic. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic or supernatural powers to inflict harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, "Witchcraft thus defined exists more in the imagination of contemporaries than in any objective reality. Yet this stereotype has a long history and has constituted for many cultures a viable explanation of evil in the world". The belief in witchcraft has been found in a great number of societies worldwide. Anthropologists have applied the English term "witchcraft" to similar beliefs in occult practices in many different cultures, and societies that have adopted the English language have often internalised the term.

Blood Law, in some traditional Native American communities, is the severe, usually capital punishment of certain serious crimes. The responsibility for delivering this justice has traditionally fallen to the family or clan of the victim, usually a male relative.

Witchcraft has been present throughout the Philippines even before Spanish colonization, and is associated with indigenous Philippine folk religions. Its practice involves black magic, specifically a malevolent use of sympathetic magic. Today, practices are said to be centered in Siquijor, Cebu, Davao, Talalora, Western Samar, and Sorsogon, where many of the country's faith healers reside. Witchcraft also exists in many of the hinterlands, especially in Samar and Leyte; however, witchcraft is known and occurs anywhere in the country.

Navajo music is music made by the Navajos, mostly hailing from the Four Corners region of the Southwestern United States and the territory of the Navajo Nation. While it traditionally takes the shape of ceremonial chants and echoes themes found in Diné Bahaneʼ, contemporary Navajo music includes a wide range of genres, ranging from country music to rock and rap, performed in both English and Navajo.

Witch smellers were important and powerful people, almost always women, amongst the Zulu and other Bantu-speaking peoples of Southern Africa, responsible for rooting out alleged evil witches in the area, and sometimes responsible for considerable bloodshed themselves. In present-day South Africa, their role has waned and their activities are illegal according to the Witchcraft Suppression Act, 1957.

Asian witchcraft encompasses various types of witchcraft practices across Asia. In ancient times, magic played a significant role in societies such as ancient Egypt and Babylonia, as evidenced by historical records. In the Middle East, references to magic can be found in the Torah and the Quran, where witchcraft is condemned due to its association with belief in magic, as it is within other Abrahamic religions.

Witchcraft in Latin America, known in Spanish as brujería, is a complex blend of indigenous, African, and European influences. Indigenous cultures had spiritual practices centered around nature and healing, while the arrival of Africans brought syncretic religions like Santería and Candomblé. European witchcraft beliefs merged with local traditions during colonization, contributing to the region's magical tapestry. Practices vary across countries, with accusations historically intertwined with social dynamics. A male practitioner is called a brujo, a female practitioner is a bruja.

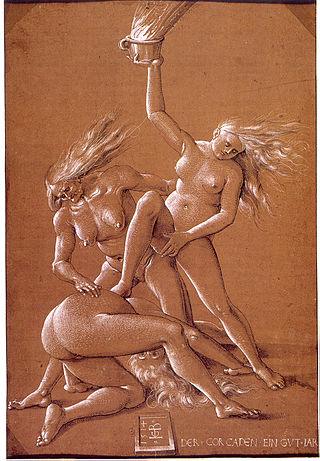

European witchcraft is a multifaceted historical and cultural phenomenon that unfolded over centuries, leaving a mark on the continent's social, religious, and legal landscapes. The roots of European witchcraft trace back to classical antiquity when concepts of magic and religion were closely related, and society closely integrated magic and supernatural beliefs. Ancient Rome, then a pagan society, had laws against harmful magic. In the Middle Ages, accusations of heresy and devil worship grew more prevalent. By the early modern period, major witch hunts began to take place, partly fueled by religious tensions, societal anxieties, and economic upheaval. Witches were often viewed as dangerous sorceresses or sorcerers in a pact with the Devil, capable of causing harm through black magic. A feminist interpretation of the witch trials is that misogynist views of women led to the association of women and malevolent witchcraft.

Skinwalkers is a 2002 mystery television film based on the novel of the same name by Tony Hillerman, one of his series of mysteries set against contemporary Navajo life in the Southwest. It features an all-Native cast, with Adam Beach and Wes Studi playing officers Jim Chee and Joe Leaphorn. It was produced as part of the PBS Mystery! series, filmed on the Navajo reservation and directed by Chris Eyre.

In June 2007 the Office of the Premier of the Mpumalanga province in South Africa leaked a draft Mpumalanga Witchcraft Suppression Bill of 2007.

Evidence of magic use and witch trials were prevalent in the Early Modern period, and Inquisitorial prosecution of witches and magic users in Italy during this period was widely documented. Primary sources unearthed from Vatican and city archives offer insights into this phenomenon, and notable Early Modern microhistorians such as Guido Ruggiero, Maria Sofia Messana, Angelo Buttice and Carlo Ginzburg, have defined their careers detailing this topic. In addition, Giovanni Romeo's monograph Inquisitori, esorcisti e streghe nell'Italia della Controriforma (1990) was considered pioneering and marked an important step forward in inquisitorial and witchcraft studies dealing with early modern Italy.In last 25 years a jurist and researcher on trials against witches, add many informations: the names of people involved in witchcraft, their jobs, the meetings. Monia Montechiarini in 'Stregoneria: Crimine Femminile', 'Streghe, eretici e benandanti del Friuli Venezia Giulia' and 'Streghe, Avvelenatrici e Cortigiane di Roma' discovered new secrets.

Ghost sickness is a cultural belief among some traditional indigenous peoples in North America, notably the Navajo, and some Muscogee and Plains cultures, as well as among Polynesian peoples. People who are preoccupied and/or consumed by the deceased are believed to suffer from ghost sickness. Reported symptoms can include general weakness, loss of appetite, suffocation feelings, recurring nightmares, and a pervasive feeling of terror. The sickness is attributed to ghosts or, occasionally, to witches or witchcraft.

Iich'aa is a culture-bound syndrome found in the Navajo Native American culture. The non-exclusive list of symptoms are: epileptic behaviour, loss of self-control, self-destructive behaviour and fits of violence and rage.

Cunning folk, also known as folk healers or wise folk, were practitioners of folk medicine, helpful folk magic and divination in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. Their practices were known as the cunning craft. Their services also included thwarting witchcraft. Although some cunning folk were denounced as witches themselves, they made up a minority of those accused, and the common people generally made a distinction between the two. The name 'cunning folk' originally referred to folk-healers and magic-workers in Britain, but the name is now applied as an umbrella term for similar people in other parts of Europe.

Navajo medicine covers a range of traditional healing practices of the Indigenous American Navajo people. It dates back thousands of years as many Navajo people have relied on traditional medicinal practices as their primary source of healing. However, modern day residents within the Navajo Nation have incorporated contemporary medicine into their society with the establishment of Western hospitals and clinics on the reservation over the last century.

Magic, Witchcraft and the Otherworld: An Anthropology is an anthropological study of contemporary Pagan and ceremonial magic groups that practiced magic in London, England, during the 1990s. It was written by English anthropologist Susan Greenwood based upon her doctoral research undertaken at Goldsmiths' College, a part of the University of London, and first published in 2000 by Berg Publishers.

Coyote is an irresponsible and trouble-making character who is nevertheless one of the most important and revered characters in Navajo mythology. Even though Tó Neinilii is the Navajo god of rain, Coyote also has powers over rain. Coyote’s ceremonial name is Áłtsé hashké which means "first scolder". In Navajo tradition, Coyote appears in creation myths, teaching stories, and healing ceremonies.

Witch trials and witch related accusations were at a high during the early modern period in Britain, a time that spanned from the beginning of the 16th century to the end of the 18th century.

The Witch trials in Portugal were perhaps the fewest in all of Europe. Similar to the Spanish Inquisition in neighboring Spain, the Portuguese Inquisition preferred to focus on the persecution of heresy and did not consider witchcraft to be a priority. In contrast to the Spanish Inquisition, however, the Portuguese Inquisition was much more efficient in preventing secular courts from conducting witch trials, and therefore almost managed to keep Portugal free from witch trials. Only seven people are known to have been executed for sorcery in Portugal.

The views of witchcraft in North America have evolved through an interlinking history of cultural beliefs and interactions. These forces contribute to complex and evolving views of witchcraft. Today, North America hosts a diverse array of beliefs about witchcraft.

References

- 1 2 Wall, Leon and William Morgan, Navajo–English Dictionary. Hippocrene Books, New York, 1998. ISBN 0-7818-0247-4.

- 1 2 3 Kluckhohn, Clyde (1962). Navaho Witchcraft. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press (Original from the University of Michigan). ISBN 9780807046975. OCLC 1295234297.

- ↑ Hampton, Carol M. "Book Review: Some Kind of Power: Navajo Children's Skinwalker Narratives " in Western Historical Quarterly. 1 July 1986. Accessed 17 Nov. 2016.

- 1 2 Keene, Dr. Adrienne, "Magic in North America Part 1: Ugh." at Native Appropriations , 8 March 2016. Accessed 9 April 2016. Quote: "the belief of these things (beings?) has a deep and powerful place in Navajo understandings of the world. It is connected to many other concepts and many other ceremonial understandings and lifeways. It is not just a scary story, or something to tell kids to get them to behave, it’s much deeper than that."

- ↑ Carter, J. (2010, October 28). The Cowboy and the Skinwalker. Ruidoso News.

- ↑ Teller, J. & Blackwater, N. (1999). The Navajo Skinwalker, Witchcraft, and Related Phenomena (1st Edition ed.). Chinle, AZ: Infinity Horn Publishing.

- 1 2 Brady, M. K. & Toelken, B. (1984). Some Kind of Power: Navajo Children's Skinwalker Narratives. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

- ↑ Salzman, Michael (October 1990). "The Construction of an Intercultural Sensitizer Training Non-Navajo Personnel". Journal of American Indian Education. 30 (1): 25–36. JSTOR 24397995.

- 1 2 Brunvand, J. H. (2012). Native American Contemporary Legends. In J. H. Brunvand, Encyclopedia of Urban Legends (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, California.

- ↑ Watson, C. (1996, August 11). "Breakfast with Skinwalkers". Star Tribune.