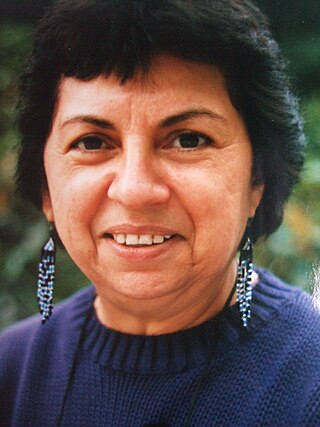

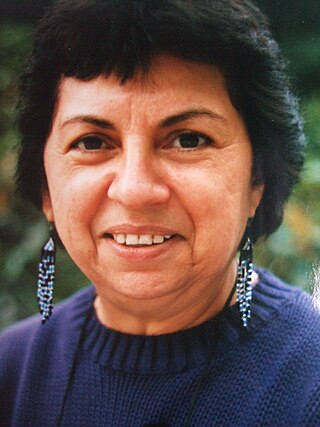

Sandra Cisneros is an American writer. She is best known for her first novel, The House on Mango Street (1983), and her subsequent short story collection, Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories (1991). Her work experiments with literary forms that investigate emerging subject positions, which Cisneros herself attributes to growing up in a context of cultural hybridity and economic inequality that endowed her with unique stories to tell. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, was awarded one of 25 new Ford Foundation Art of Change fellowships in 2017, and is regarded as a key figure in Chicano literature.

Cherríe Moraga is a Xicana feminist, writer, activist, poet, essayist, and playwright. She is part of the faculty at the University of California, Santa Barbara in the Department of English since 2017, and in 2022 became a distinguished professor. Moraga is also a founding member of the social justice activist group La Red Xicana Indígena, which is network fighting for education, culture rights, and Indigenous Rights. In 2017, she co-founded, with Celia Herrera Rodríguez, Las Maestras Center for Xicana Indigenous Thought, Art, and Social Practice, located on the campus of UC Santa Barbara.

Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa was an American scholar of Chicana feminism, cultural theory, and queer theory. She loosely based her best-known book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), on her life growing up on the Mexico–Texas border and incorporated her lifelong experiences of social and cultural marginalization into her work. She also developed theories about the marginal, in-between, and mixed cultures that develop along borders, including on the concepts of Nepantla, Coyoxaulqui imperative, new tribalism, and spiritual activism. Her other notable publications include This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), co-edited with Cherríe Moraga.

Ana Castillo is a Chicana novelist, poet, short story writer, essayist, editor, playwright, translator and independent scholar. Considered one of the leading voices in Chicana experience, Castillo is most known for her experimental style as a Latina novelist and for her intervention in Chicana feminism known as Xicanisma.

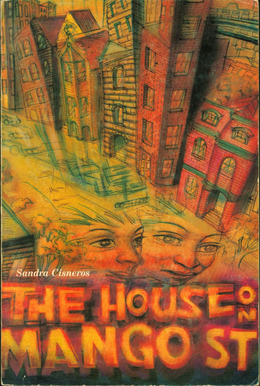

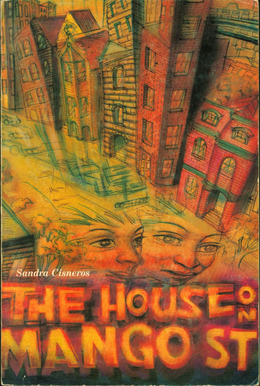

The House on Mango Street is a 1984 novel by Mexican-American author Sandra Cisneros. Structured as a series of vignettes, it tells the story of Esperanza Cordero, a 12-year-old Chicana girl growing up in the Hispanic quarter of Chicago. Based in part on Cisneros's own experience, the novel follows Esperanza over the span of one year in her life, as she enters adolescence and begins to face the realities of life as a young woman in a poor and patriarchal community. Elements of the Mexican-American culture and themes of social class, race, sexuality, identity, and gender are interwoven throughout the novel.

Chicana feminism is a sociopolitical movement, theory, and praxis that scrutinizes the historical, cultural, spiritual, educational, and economic intersections impacting Chicanas and the Chicana/o community in the United States. Chicana feminism empowers women to challenge institutionalized social norms and regards anyone a feminist who fights for the end of women's oppression in the community.

Chicano poetry is a subgenre of Chicano literature that stems from the cultural consciousness developed in the Chicano Movement. Chicano poetry has its roots in the reclamation of Chicana/o as an identity of empowerment rather than denigration. As a literary field, Chicano poetry emerged in the 1960s and formed its own independent literary current and voice.

Alicia Gaspar de Alba is an American scholar, cultural critic, novelist, and poet whose works include historical novels and scholarly studies on Chicana/o art, culture and sexuality.

Mexican American literature is literature written by Mexican Americans in the United States. Although its origins can be traced back to the sixteenth century, the bulk of Mexican American literature dates from post-1848 and the United States annexation of large parts of Mexico in the wake of the Mexican–American War. Today, as a part of American literature in general, this genre includes a vibrant and diverse set of narratives, prompting critics to describe it as providing "a new awareness of the historical and cultural independence of both northern and southern American hemispheres". Chicano literature is an aspect of Mexican American literature.

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza is a 1987 semi-autobiographical work by Gloria E. Anzaldúa that examines the Chicano and Latino experience through the lens of issues such as gender, identity, race, and colonialism. Borderlands is considered to be Anzaldúa’s most well-known work and a pioneering piece of Chicana literature.

Graciela Limón is a Latina/Chicana novelist and a former university professor. She has been honored with an American Book Award and the Luis Leal Award for Distinction in Chicano/Latino Literature.

Chicana literature is a form of literature that has emerged from the Chicana Feminist movement. It aims to redefine Chicana archetypes in an effort to provide positive models for Chicanas. Chicana writers redefine their relationships with what Gloria Anzaldúa has called "Las Tres Madres" of Mexican culture by depicting them as feminist sources of strength and compassion.

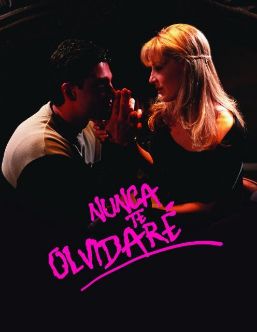

Nunca te olvidaré is a Mexican telenovela produced by Juan Osorio and Carlos Moreno Laguillo for Televisa in 1999. It is based on a novel by Caridad Bravo Adams. It aired on Canal de Las Estrellas from January 18, 1999 to May 28, 1999.

La Loca is a literary mythotype of the mad heroine found in Chicana literature related to La Llorona. Authors using the figure include Ana Castillo, Sandra Cisneros and Monica Palacios, as well as in the poem "La Loca de la Raza Cósmica" by the pseudonymous La Chrisx.

Third Woman Press (TWP) is a Queer and Feminist of Color publisher forum committed to feminist and queer of color decolonial politics and projects. It was founded in 1979 by Norma Alarcón in Bloomington, Indiana. She aimed to create a new political class surrounding sexuality, race, and gender. Alarcón wrote that "Third Woman is one forum, for the self-definition and the self-invention which is more than reformism, more than revolt. The title Third Woman refers to that pre-ordained reality that we have been born to and continues to live and experience and be a witness to, despite efforts toward change ..."

Emma Pérez is an American author and professor, known for her work in queer Chicana feminist studies.

The term Chicanafuturism was originated by scholar Catherine S. Ramírez which she introduced in Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies in 2004. The term is a portmanteau of 'chicana' and 'futurism', inspired by the developing movement of Afrofuturism. The word 'chicana' refers to a woman or girl of Mexican origin or descent. However, 'Chicana' itself serves as a chosen identity for many female Mexican Americans in the United States, to express self-determination and solidarity in a shared cultural, ethnic, and communal identity while openly rejecting assimilation. Ramírez created the concept of Chicanafuturism as a response to white androcentrism that she felt permeated science-fiction and American society. Chicanafuturism can be understood as part of a larger genre of Latino futurisms.

Spiritual activism is a practice that brings together the otherworldly and inward-focused work of spirituality and the outwardly-focused work of activism. Spiritual activism asserts that these two practices are inseparable and calls for a recognition that the binaries of inward/outward, spiritual/material, and personal/political all form part of a larger interconnected whole between and among all living things. In an essay on queer Chicana feminist and theorist Gloria E. Anzaldúa's reflections on spiritual activist practice, AnaLouise Keating states that "spiritual activism is spirituality for social change, spirituality that posits a relational worldview and uses this holistic worldview to transform one's self and one's worlds."

Janeth Paola Cabezas Castillo is an Ecuadorian politician and former television presenter. She was the Governor of Esmeraldas Province from 2013 to 2016 and is a current member of Ecuador's National Assembly for the Citizen Revolution Movement (RC). Cabezas was elected leader of the largest political coalition in the 2021 National Assembly, the Union for Hope (UNES).

Chicano literature is an aspect of Mexican-American literature that emerged from the cultural consciousness developed in the Chicano Movement. Chicano literature formed out of the political and cultural struggle of Chicana/os to develop a political foundation and identity that rejected Anglo-American hegemony. This literature embraced the pre-Columbian roots of Mexican-Americans, especially those who identify as Chicana/os.