Related Research Articles

Victimology is the study of victimization, including the psychological effects on victims, the relationship between victims and offenders, the interactions between victims and the criminal justice system—that is, the police and courts, and corrections officials—and the connections between victims and other social groups and institutions, such as the media, businesses, and social movements.

Juvenile delinquency, also known as juvenile offending, is the act of participating in unlawful behavior as a minor or individual younger than the statutory age of majority. The term delinquent usually refers to juvenile delinquency, and is also generalised to refer to a young person who behaves an unacceptable way.

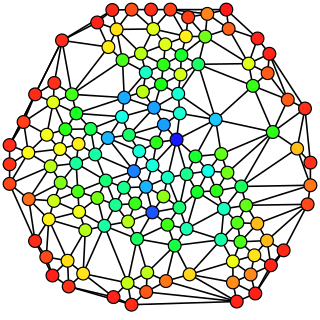

In graph theory, a clustering coefficient is a measure of the degree to which nodes in a graph tend to cluster together. Evidence suggests that in most real-world networks, and in particular social networks, nodes tend to create tightly knit groups characterised by a relatively high density of ties; this likelihood tends to be greater than the average probability of a tie randomly established between two nodes.

In graph theory and network analysis, indicators of centrality assign numbers or rankings to nodes within a graph corresponding to their network position. Applications include identifying the most influential person(s) in a social network, key infrastructure nodes in the Internet or urban networks, super-spreaders of disease, and brain networks. Centrality concepts were first developed in social network analysis, and many of the terms used to measure centrality reflect their sociological origin.

Environmental criminology focuses on criminal patterns within particular built environments and analyzes the impacts of these external variables on people's cognitive behavior. It forms a part of criminology's Positivist School in that it applies the scientific method to examine the society that causes crime.

In graph theory, eigenvector centrality is a measure of the influence of a node in a network. Relative scores are assigned to all nodes in the network based on the concept that connections to high-scoring nodes contribute more to the score of the node in question than equal connections to low-scoring nodes. A high eigenvector score means that a node is connected to many nodes who themselves have high scores.

Right realism, in criminology, also known as New Right Realism, Neo-Classicism, Neo-Positivism, or Neo-Conservatism, is the ideological polar opposite of left realism. It considers the phenomenon of crime from the perspective of political conservatism and asserts that it takes a more realistic view of the causes of crime and deviance, and identifies the best mechanisms for its control. Unlike the other schools of criminology, there is less emphasis on developing theories of causality in relation to crime and deviance. The school employs a rationalist, direct and scientific approach to policy-making for the prevention and control of crime. Some politicians who ascribe to the perspective may address aspects of crime policy in ideological terms by referring to freedom, justice, and responsibility. For example, they may be asserting that individual freedom should only be limited by a duty not to use force against others. This, however, does not reflect the genuine quality in the theoretical and academic work and the real contribution made to the nature of criminal behaviour by criminologists of the school.

In criminology, social control theory proposes that exploiting the process of socialization and social learning builds self-control and reduces the inclination to indulge in behavior recognized as antisocial. It derived from functionalist theories of crime and was developed by Ivan Nye (1958), who proposed that there were three types of control:

The Positivist School was founded by Cesare Lombroso and led by two others: Enrico Ferri and Raffaele Garofalo. In criminology, it has attempted to find scientific objectivity for the measurement and quantification of criminal behavior. Its method was developed by observing the characteristics of criminals to observe what may be the root cause of their behavior or actions. Since the Positivist's school of ideas came around, research revolving around its ideas has sought to identify some of the key differences between those who were deemed "criminals" and those who were not, often without considering flaws in the label of what a “criminal” is.

In criminology, rational choice theory adopts a utilitarian belief that humans are reasoning actors who weigh means and ends, costs and benefits, in order to make a rational choice. This method was designed by Cornish and Clarke to assist in thinking about situational crime prevention.

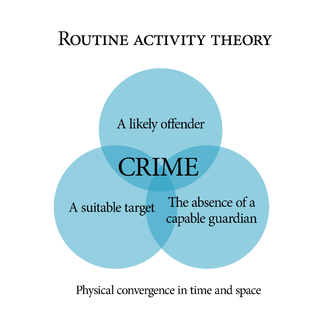

Routine activity theory is a sub-field of crime opportunity theory that focuses on situations of crimes. It was first proposed by Marcus Felson and Lawrence E. Cohen in their explanation of crime rate changes in the United States between 1947 and 1974. The theory has been extensively applied and has become one of the most cited theories in criminology. Unlike criminological theories of criminality, routine activity theory studies crime as an event, closely relates crime to its environment and emphasizes its ecological process, thereby diverting academic attention away from mere offenders.

Quantitative methods provide the primary research methods for studying the distribution and causes of crime. Quantitative methods provide numerous ways to obtain data that are useful to many aspects of society. The use of quantitative methods such as survey research, field research, and evaluation research as well as others. The data can, and is often, used by criminologists and other social scientists in making causal statements about variables being researched.

Network science is an academic field which studies complex networks such as telecommunication networks, computer networks, biological networks, cognitive and semantic networks, and social networks, considering distinct elements or actors represented by nodes and the connections between the elements or actors as links. The field draws on theories and methods including graph theory from mathematics, statistical mechanics from physics, data mining and information visualization from computer science, inferential modeling from statistics, and social structure from sociology. The United States National Research Council defines network science as "the study of network representations of physical, biological, and social phenomena leading to predictive models of these phenomena."

In a connected graph, closeness centrality of a node is a measure of centrality in a network, calculated as the reciprocal of the sum of the length of the shortest paths between the node and all other nodes in the graph. Thus, the more central a node is, the closer it is to all other nodes.

The self-control theory of crime, often referred to as the general theory of crime, is a criminological theory about the lack of individual self-control as the main factor behind criminal behavior. The self-control theory of crime suggests that individuals who were ineffectually parented before the age of ten develop less self-control than individuals of approximately the same age who were raised with better parenting. Research has also found that low levels of self-control are correlated with criminal and impulsive conduct.

The correlates of crime explore the associations of specific non-criminal factors with specific crimes.

In graph theory, betweenness centrality is a measure of centrality in a graph based on shortest paths. For every pair of vertices in a connected graph, there exists at least one shortest path between the vertices such that either the number of edges that the path passes through or the sum of the weights of the edges is minimized. The betweenness centrality for each vertex is the number of these shortest paths that pass through the vertex.

Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency is a peer-reviewed academic journal that publishes papers in the field of Criminology. The journal's editors Jean McGloin and Chris Sullivan. It has been in publication since 1964 and is currently published by SAGE Publications.

Criminology is the interdisciplinary study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is a multidisciplinary field in both the behavioural and social sciences, which draws primarily upon the research of sociologists, political scientists, economists, legal sociologists, psychologists, philosophers, psychiatrists, social workers, biologists, social anthropologists, scholars of law and jurisprudence, as well as the processes that define administration of justice and the criminal justice system.

Walter Reckless was an American criminologist known for his containment theory.

References

- ↑ Brantingham, P. L. & Brantigham, P. J. "Crime Pattern Theory" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-18.

- 1 2 Carlo Morselli and Cynthia Giguere (2006). Legitimate strengths in criminal networks. Crime, Law & Social Change, 185-200.

- 1 2 Aili Malm & Gisela Bichler (2011). "Networks of Collaborating Criminals: Assessing the Structural Vulnerability of Drug Markets". Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 48 (2): 271–297. doi:10.1177/0022427810391535. S2CID 146367842.

- ↑ Lichtenwald, T.G. & Perri, F.S. (2013). "Terrorist use of smuggling tunnels" (PDF). International Journal of Criminology and Sociology. 2: 210–226.

- ↑ Papachristos, A. V. (2011). The coming of a networked criminology. In J. MacDonald (ED.), Measuring crime and criminality (pp. 101–140). New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers.

- ↑ Morselli, C. (2009). Inside criminal networks, studies of organized crime. Springer Social Sciences-Criminology and Criminal Justice, 8, ISBN 978-0-387-09526-4.

- ↑ Malm, A. E., Kinney, J. B.,& Pollard, N.R. (2008). "Social network and Distance Correlates of Criminal Associates Involved in Illicit Drug Production". Security Journal. 21 (1–2): 77–94. doi:10.1057/palgrave.sj.8350069. S2CID 154289911.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Qin, J., Xu, J.J., Hu, D., Sageman, M., & Chen, H. (2005). Analyzing terrorist networks: A case study of the Global Salafi Jihad network. IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics, ISI 2005, Atlanta, GA, USA, May 19–20, 2005. Proceedings.

- ↑ Shelley, J., Picarelli, A.I., Hart, D.M., Craig-Hart, P.A., Williams, P.,Simon, S., & Covill, L. (2005). "Methods and motives: Exploring links between transnational organized crime and international terrorism" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Sageman, M. (2004). Understanding Terror Networks. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

- ↑ Snijders, T. A. B. (2001). "The statistical evaluation of social network dynamics". Sociological Methods. 31: 361–95. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.11.1911 . doi:10.1111/0081-1750.00099.

- ↑ Coles, N. (2001). "It's not what you know-it's who you know that counts: Analyzing serious crime groups as social networks". British Journal of Criminology. 41 (4): 580–594. doi:10.1093/bjc/41.4.580.

- ↑ P. Brantingham & P. Brantingham (1994). "The Influence of Street Networks on the Patterning of Property Offenses" (PDF). In Clarke (ed.). Crime Prevention Studies. Vol. 2. Monsey, N.Y.: Criminal Justice Press.

- ↑ Brantingham, P. J., & Brantingham, P. L. (1998). "Environmental criminology: From theory to urban planning practice". Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention. 7: 31–60.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Bichler, Gisela M., Aili Malm, and Janet Enriquez (2010). "Magnetic Facilities: Identifying the Convergence Settings of Juvenile Delinquents". Crime & Delinquency. 60 (7): 1–28. doi:10.1177/0011128710382349. S2CID 146769456.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Bichler, Gisela C.-M., Jill Christie-Merral, and Dale Sechrest (2011). "Examining Juvenile Delinquency within Activity Space: Building a Context for Offender Travel Patterns". Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 48 (3): 472–506. doi:10.1177/0022427810393014. S2CID 145122715.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)