Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psycho-social intervention that aims to reduce symptoms of various mental health conditions, primarily depression and anxiety disorders. Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the most effective means of treatment for substance abuse and co-occurring mental health disorders. CBT focuses on challenging and changing cognitive distortions and their associated behaviors to improve emotional regulation and develop personal coping strategies that target solving current problems. Though it was originally designed to treat depression, its uses have been expanded to include many issues and the treatment of many mental health conditions, including anxiety, substance use disorders, marital problems, ADHD, and eating disorders. CBT includes a number of cognitive or behavioral psychotherapies that treat defined psychopathologies using evidence-based techniques and strategies.

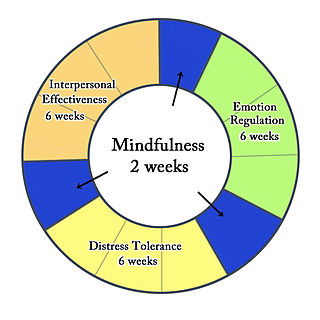

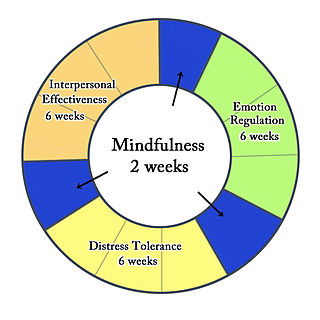

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that began with efforts to treat personality disorders and interpersonal conflicts. Evidence suggests that DBT can be useful in treating mood disorders and suicidal ideation as well as for changing behavioral patterns such as self-harm and substance use. DBT evolved into a process in which the therapist and client work with acceptance and change-oriented strategies and ultimately balance and synthesize them—comparable to the philosophical dialectical process of thesis and antithesis, followed by synthesis.

Depressive realism is the hypothesis developed by Lauren Alloy and Lyn Yvonne Abramson that depressed individuals make more realistic inferences than non-depressed individuals. Although depressed individuals are thought to have a negative cognitive bias that results in recurrent, negative automatic thoughts, maladaptive behaviors, and dysfunctional world beliefs, depressive realism argues not only that this negativity may reflect a more accurate appraisal of the world but also that non-depressed individuals' appraisals are positively biased.

Social support is the perception and actuality that one is cared for, has assistance available from other people, and most popularly, that one is part of a supportive social network. These supportive resources can be emotional, informational, or companionship ; tangible or intangible. Social support can be measured as the perception that one has assistance available, the actual received assistance, or the degree to which a person is integrated in a social network. Support can come from many sources, such as family, friends, pets, neighbors, coworkers, organizations, etc.

The Dodo bird verdict is a controversial topic in psychotherapy, referring to the claim that all empirically validated psychotherapies, regardless of their specific components, produce equivalent outcomes. It is named after the Dodo character in Alice in Wonderland. The conjecture was introduced by Saul Rosenzweig in 1936, drawing on imagery from Lewis Carroll's novel Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, but only came into prominence with the emergence of new research evidence in the 1970s.

Caring in intimate relationships is the practice of providing care and support to an intimate relationship partner. Caregiving behaviours are aimed at reducing the partner's distress and supporting their coping efforts in situations of either threat or challenge. Caregiving may include emotional support and/or instrumental support. Effective caregiving behaviour enhances the care-recipient's psychological well-being, as well as the quality of the relationship between the caregiver and the care-recipient. However, certain suboptimal caregiving strategies may be either ineffective or even detrimental to coping.

Positive illusions are unrealistically favorable attitudes that people have towards themselves or to people that are close to them. Positive illusions are a form of self-deception or self-enhancement that feel good; maintain self-esteem; or avoid discomfort, at least in the short term. There are three general forms: inflated assessment of one's own abilities, unrealistic optimism about the future, and an illusion of control. The term "positive illusions" originates in a 1988 paper by Taylor and Brown. "Taylor and Brown's (1988) model of mental health maintains that certain positive illusions are highly prevalent in normal thought and predictive of criteria traditionally associated with mental health."

Leslie Samuel Greenberg is a Canadian psychologist born in Johannesburg, South Africa, and is one of the originators and primary developers of Emotion-Focused Therapy for individuals and couples. He is a professor emeritus of psychology at York University in Toronto, and also director of the Emotion-Focused Therapy Clinic in Toronto. His research has addressed questions regarding empathy, psychotherapy process, the therapeutic alliance, and emotion in human functioning.

Emotional self-regulation or emotion regulation is the ability to respond to the ongoing demands of experience with the range of emotions in a manner that is socially tolerable and sufficiently flexible to permit spontaneous reactions as well as the ability to delay spontaneous reactions as needed. It can also be defined as extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions. Emotional self-regulation belongs to the broader set of emotion regulation processes, which includes both the regulation of one's own feelings and the regulation of other people's feelings.

Behavioral theories of depression explain the etiology of depression based on the behavioural sciences, and they form the basis for behavioral therapies for depression.

Rumination is the focused attention on the symptoms of one's mental distress, and on its possible causes and consequences, as opposed to its solutions, according to the Response Styles Theory proposed by Nolen-Hoeksema (1998).

Positive affectivity (PA) is a human characteristic that describes how much people experience positive affects ; and as a consequence how they interact with others and with their surroundings.

In psychology, avoidance coping is a coping mechanism and form of experiential avoidance. It is characterized by a person's efforts, conscious or unconscious, to avoid dealing with a stressor in order to protect oneself from the difficulties the stressor presents. Avoidance coping can lead to substance abuse, social withdrawal, and other forms of escapism. High levels of avoidance behaviors may lead to a diagnosis of avoidant personality disorder, though not everyone who displays such behaviors meets the definition of having this disorder. Avoidance coping is also a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder and related to symptoms of depression and anxiety. Additionally, avoidance coping is part of the approach-avoidance conflict theory introduced by psychologist Kurt Lewin.

Victimization refers to a person being made into a victim by someone else and can take on psychological as well as physical forms, both of which are damaging to victims. Forms of victimization include bullying or peer victimization, physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, robbery, and assault. Some of these forms of victimization are commonly associated with certain populations, but they can happen to others as well. For example, bullying or peer victimization is most commonly studied in children and adolescents but also takes place between adults. Although anyone may be victimized, particular groups may be more susceptible to certain types of victimization and as a result to the symptoms and consequences that follow. Individuals respond to victimization in a wide variety of ways, so noticeable symptoms of victimization will vary from person to person. These symptoms may take on several different forms, be associated with specific forms of victimization, and be moderated by individual characteristics of the victim and/or experiences after victimization.

Goal orientation, or achievement orientation, is an "individual disposition towards developing or validating one's ability in achievement settings". In general, an individual can be said to be mastery or performance oriented, based on whether one's goal is to develop one's ability or to demonstrate one's ability, respectively. A mastery orientation is also sometimes referred to as a learning orientation.

Experiential avoidance (EA) has been broadly defined as attempts to avoid thoughts, feelings, memories, physical sensations, and other internal experiences — even when doing so creates harm in the long run. The process of EA is thought to be maintained through negative reinforcement — that is, short-term relief of discomfort is achieved through avoidance, thereby increasing the likelihood that the avoidance behavior will persist. Importantly, the current conceptualization of EA suggests that it is not negative thoughts, emotions, and sensations that are problematic, but how one responds to them that can cause difficulties. In particular, a habitual and persistent unwillingness to experience uncomfortable thoughts and feelings is thought to be linked to a wide range of problems.

Self-concealment is a psychological construct defined as "a predisposition to actively conceal from others personal information that one perceives as distressing or negative". Its opposite is self-disclosure.

Self-control therapy is a behavioral treatment method based on a self-control model of depression, that was modeled after Frederick Kanfer's behavioral (1971) model of self-control.

The Coping Cat program is a CBT manual-based and comprehensive treatment program for children from 7 to 13 years old with separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and/or related anxiety disorders. It was designed by Philip C. Kendall, PhD, ABPP, and colleagues at the Child and Adolescent Anxiety Disorders Clinic at Temple University. A related program called C.A.T. Project is aimed at adolescents aged 14 to 17. See the publishers webpage [www.WorkbookPublishing.com]

Emotional approach coping is a psychological construct that involves the use of emotional processing and emotional expression in response to a stressful situation. As opposed to emotional avoidance, in which emotions are experienced as a negative, undesired reaction to a stressful situation, emotional approach coping involves the conscious use of emotional expression and processing to better deal with a stressful situation. The construct was developed to explain an inconsistency in the stress and coping literature: emotion-focused coping was associated with largely maladaptive outcomes while emotional processing and expression was demonstrated to be beneficial.