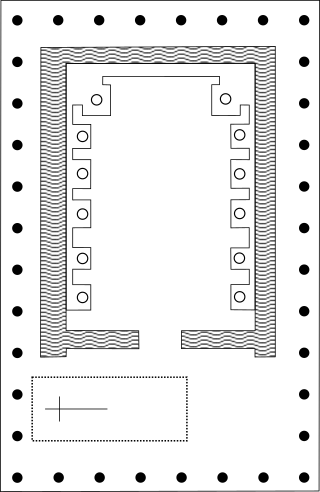

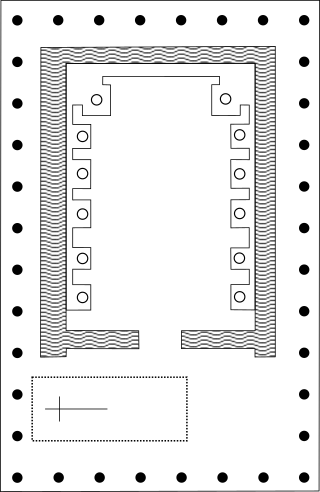

Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras. Although inspired by Iranian worship of the Zoroastrian divinity (yazata) Mithra, the Roman Mithras was linked to a new and distinctive imagery, and the level of continuity between Persian and Greco-Roman practice remains debatable. The mysteries were popular among the Imperial Roman army from the 1st to the 4th century CE.

A solar deity or sun deity is a deity who represents the Sun or an aspect thereof. Such deities are usually associated with power and strength. Solar deities and Sun worship can be found throughout most of recorded history in various forms. The Sun is sometimes referred to by its Latin name Sol or by its Greek name Helios. The English word sun derives from Proto-Germanic *sunnǭ.

The Ides of March is the 74th day in the Roman calendar, corresponding to 15 March. It was marked by several religious observances and was a deadline for settling debts in Rome. In 44 BC, it became notorious as the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar, which made the Ides of March a turning point in Roman history.

Year 274 (CCLXXIV) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Aurelianus and Capitolinus. The denomination 274 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

In Sabine and ancient Roman religion and myth, Luna is the divine embodiment of the Moon. She is often presented as the female complement of the Sun, Sol, conceived of as a god. Luna is also sometimes represented as an aspect of the Roman triple goddess, along with Diana and either Proserpina or Hecate. Luna is not always a distinct goddess, but sometimes rather an epithet that specializes a goddess, since both Diana and Juno are identified as moon goddesses.

In classical Latin, the epithet Indiges, singular in form, is applied to Sol (Sol Indiges) and to Jupiter of Lavinium, later identified with Aeneas. One theory holds that it means the "speaker within", and stems from before the recognition of divine persons. Another, which the Oxford Classical Dictionary holds more likely, is that it means "invoked" in the sense of "pointing at", as in the related word indigitamenta.

Elagabalus, Aelagabalus, Heliogabalus, or simply Elagabal was an Arab-Roman sun god, initially venerated in Emesa, Syria. Although there were many variations of the name, the god was consistently referred to as Elagabalus in Roman coins and inscriptions from AD 218 on, during the reign of emperor Elagabalus.

Saturnalia is an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through 19 December. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, and a public banquet, followed by private gift-giving, continual partying, and a carnival atmosphere that overturned Roman social norms: gambling was permitted, and masters provided table service for their slaves as it was seen as a time of liberty for both slaves and freedmen alike. A common custom was the election of a "King of the Saturnalia", who gave orders to people, which were followed and presided over the merrymaking. The gifts exchanged were usually gag gifts or small figurines made of wax or pottery known as sigillaria. The poet Catullus called it "the best of days".

Festivals in ancient Rome were a very important part in Roman religious life during both the Republican and Imperial eras, and one of the primary features of the Roman calendar. Feriae were either public (publicae) or private (privatae). State holidays were celebrated by the Roman people and received public funding. Games (ludi), such as the Ludi Apollinares, were not technically feriae, but the days on which they were celebrated were dies festi, holidays in the modern sense of days off work. Although feriae were paid for by the state, ludi were often funded by wealthy individuals. Feriae privatae were holidays celebrated in honor of private individuals or by families. This article deals only with public holidays, including rites celebrated by the state priests of Rome at temples, as well as celebrations by neighborhoods, families, and friends held simultaneously throughout Rome.

Sol Invictus was the official sun god of the late Roman Empire and a later version of the god Sol. The emperor Aurelian revived his cult in AD 274 and promoted Sol Invictus as the chief god of the empire. The main festival dedicated to him was the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti on 25 December, the date of the winter solstice in the Roman calendar. From Aurelian onward, Sol was of supreme importance, and often appeared on imperial coinage. He was often shown wearing a sun crown and driving a horse-drawn chariot through the sky. His prominence lasted until the emperor Constantine I established Christianity as the Imperial religion. The last inscription referring to Sol Invictus dates to AD 387, although there were enough devotees in the fifth century that the Christian theologian Augustine found it necessary to preach against them.

An Agonalia or Agonia was an obscure archaic religious observance celebrated in ancient Rome several times a year, in honor of various divinities. Its institution, like that of other religious rites and ceremonies, was attributed to Numa Pompilius, the semi-legendary second king of Rome. Ancient calendars indicate that it was celebrated regularly on January 9, May 21, and December 11.

The Elagabalium was a temple built by the Roman emperor Elagabalus, located on the north-east corner of the Palatine Hill. During Elagabalus' reign from 218 until 222, the Elagabalium was the center of a controversial religious cult, dedicated to Elagabalus, of which the emperor himself was the high priest.

Malakbel was a sun god worshipped in the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra, frequently associated and worshipped with the moon god Aglibol as a party of a trinity involving the sky god Baalshamin.

The term Christianized calendar refers to feast days which are Christianized reformulations of feasts from pre-Christian times.

The winter solstice, also called the hibernal solstice, occurs when either of Earth's poles reaches its maximum tilt away from the Sun. This happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere. For that hemisphere, the winter solstice is the day with the shortest period of daylight and longest night of the year, and when the Sun is at its lowest daily maximum elevation in the sky. Each polar region experiences continuous darkness or twilight around its winter solstice.

The Sun, as the source of energy and light for life on Earth, has been a central object in culture and religion since prehistory. Ritual solar worship has given rise to solar deities in theistic traditions throughout the world, and solar symbolism is ubiquitous. Apart from its immediate connection to light and warmth, the Sun is also important in timekeeping as the main indicator of the day and the year.

The Roman cult of Mithras had connections with other pagan deities, syncretism being a prominent feature of Roman paganism. Almost all Mithraea contain statues dedicated to gods of other cults, and it is common to find inscriptions dedicated to Mithras in other sanctuaries, especially those of Jupiter Dolichenus. Mithraism was not an alternative to other pagan religions, but rather a particular way of practising pagan worship; and many Mithraic initiates can also be found worshipping in the civic religion, and as initiates of other mystery cults.

Dies natalis is Latin for "birthday, anniversary" and may refer to:

The date of the birth of Jesus is not stated in the gospels or in any historical sources and the evidence is too incomplete and contradictory to allow for consistent dating. However, most biblical scholars and ancient historians believe that his birth date is around 4 to 6 BC. Two main approaches have been used to estimate the year of the birth of Jesus: one based on the accounts in the Gospels of his birth with reference to King Herod's reign, and the other by subtracting his stated age of "about 30 years" when he began preaching.