Asperger syndrome (AS), also known as Asperger's syndrome or Asperger's, formerly described as a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by significant difficulties in social interaction and nonverbal communication, along with restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior and interests. Asperger syndrome has been merged with other disorders into autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and is no longer considered a stand-alone diagnosis. It was considered milder than other diagnoses which were merged into ASD due to relatively unimpaired spoken language and intelligence.

Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) is a historic psychiatric diagnosis first defined in 1980 that has since been incorporated into autism spectrum disorder in the DSM-5 (2013).

Diagnoses of autism have become more frequent since the 1980s, which has led to various controversies about both the cause of autism and the nature of the diagnoses themselves. Whether autism has mainly a genetic or developmental cause, and the degree of coincidence between autism and intellectual disability, are all matters of current scientific controversy as well as inquiry. There is also more sociopolitical debate as to whether autism should be considered a disability on its own.

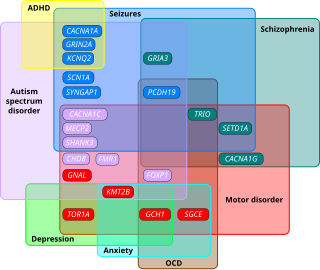

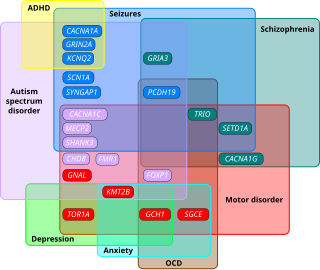

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are neurodevelopmental disorders that begin in early childhood, persist throughout adulthood, and affect three crucial areas of development: communication, social interaction and restricted patterns of behavior. There are many conditions comorbid to autism spectrum disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy.

Sir Simon Philip Baron-Cohen is a British clinical psychologist and professor of developmental psychopathology at the University of Cambridge. He is the director of the university's Autism Research Centre and a Fellow of Trinity College.

High-functioning autism (HFA) was historically an autism classification where a person exhibits no intellectual disability, but may experience difficulty in communication, emotion recognition, expression, and social interaction.

Autism therapies include a wide variety of therapies that help people with autism, or their families. Such methods of therapy seek to aid autistic people in dealing with difficulties and increase their functional independence.

Autistic art is artwork created by autistic artists that captures or conveys a variety of autistic experiences. According to a 2021 article in Cognitive Processing, autistic artists with improved linguistic and communication skills often show a greater degree of originality and attention to detail than their neurotypical counterparts, with a positive correlation between artistic talent and high linguistic functioning. Autistic art is often considered outsider art. Art by autistic artists has long been shown in separate venues from artists without disabilities. The works of some autistic artists have featured in art publications and documentaries and been exhibited in mainstream galleries. Although autistic artists seldom received formal art education in the past, recent inclusivity initiatives have made it easier for autistic artists to get a formal college education. The Aspergers/Autism Network's AANE Artist Collaborative is an example of an art organization for autistic adults.

Societal and cultural aspects of autism or sociology of autism come into play with recognition of autism, approaches to its support services and therapies, and how autism affects the definition of personhood. The autistic community is divided primarily into two camps; the autism rights movement and the pathology paradigm. The pathology paradigm advocates for supporting research into therapies, treatments, and/or a cure to help minimize or remove autistic traits, seeing treatment as vital to help individuals with autism, while the neurodiversity movement believes autism should be seen as a different way of being and advocates against a cure and interventions that focus on normalization, seeing it as trying to exterminate autistic people and their individuality. Both are controversial in autism communities and advocacy which has led to significant infighting between these two camps. While the dominant paradigm is the pathology paradigm and is followed largely by autism research and scientific communities, the neurodiversity movement is highly popular among most autistic people, within autism advocacy, autism rights organizations, and related neurodiversity approaches have been rapidly growing and applied in the autism research field in the last few years.

Asperger syndrome (AS) was formerly a separate diagnosis under autism spectrum disorder. Under the DSM-5 and ICD-11, patients formerly diagnosable with Asperger syndrome are diagnosable with Autism Spectrum Disorder. The term is considered offensive by some autistic individuals. It was named after Hans Asperger (1906–80), who was an Austrian psychiatrist and pediatrician. An English psychiatrist, Lorna Wing, popularized the term "Asperger's syndrome" in a 1981 publication; the first book in English on Asperger syndrome was written by Uta Frith in 1991 and the condition was subsequently recognized in formal diagnostic manuals later in the 1990s.

Classic autism, also known as childhood autism, autistic disorder, (early) infantile autism, infantile psychosis, Kanner's autism, Kanner's syndrome, or (formerly) just autism, is a neurodevelopmental condition first described by Leo Kanner in 1943. It is characterized by atypical and impaired development in social interaction and communication as well as restricted, repetitive behaviors, activities, and interests. These symptoms first appear in early childhood and persist throughout life.

Autism, formally called autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or autism spectrum condition (ASC), is a neurodevelopmental disorder marked by deficits in reciprocal social communication, and the presence of restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior. Other common signs include difficulties with social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, perseverative interests, stereotypic body movements (stimming), rigid routines, and hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input. Autism is clinically regarded as a spectrum disorder, meaning that it can manifest very differently in each person. For example, some are nonspeaking, while others have proficient spoken language. Because of this, there is wide variation in the support needs of people across the autism spectrum.

Gunilla Gerland is a Swedish author and lecturer on the topic of autism. Her written works include Secrets to Success for Professionals in the Autism Field: An Insider's Guide to Understanding the Autism Spectrum, the Environment and Your Role and her autobiography A Real Person: Life on the Outside.

The history of autism spans over a century; autism has been subject to varying treatments, being pathologized or being viewed as a beneficial part of human neurodiversity. The understanding of autism has been shaped by cultural, scientific, and societal factors, and its perception and treatment change over time as scientific understanding of autism develops.

Sex and gender differences in autism exist regarding prevalence, presentation, and diagnosis.

Discrimination against autistic people is the discrimination, persecution, and oppression that autistic people have been subjected to. Discrimination against autistic people is a form of ableism.

Caetextia is a term and concept first coined by psychologists Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrell to describe a chronic disorder that manifests as a context blindness in people on the autism spectrum. It was specifically used to designate the most dominant manifestation of autistic behaviour in higher-functioning individuals. Griffin and Tyrell also suggested that caetextia "is a more accurate and descriptive term for this inability to see how one variable influences another, particularly at the higher end of the spectrum, than the label of 'Asperger's syndrome'".

Current research indicates that autistic people have higher rates of LGBT identities and feelings than the general population. A variety of explanations for this have been proposed, such as prenatal hormonal exposure, which has been linked with sexual orientation, gender dysphoria and autism. Alternatively, autistic people may be less reliant on social norms and thus are more open about their orientation or gender identity. A narrative review published in 2016 stated that while various hypotheses have been proposed for an association between autism and gender dysphoria, they lack strong evidence.

The theory of the double empathy problem is a psychological and sociological theory first coined in 2012 by Damian Milton, an autistic autism researcher. This theory proposes that many of the difficulties autistic individuals face when socializing with non-autistic individuals are due, in part, to a lack of mutual understanding between the two groups, meaning that most autistic people struggle to understand and empathize with non-autistic people, whereas most non-autistic people also struggle to understand and empathize with autistic people. This lack of understanding may stem from bidirectional differences in communication style, social-cognitive characteristics, and experiences between autistic and non-autistic individuals, but not necessarily an inherent deficiency. Recent studies have shown that most autistic individuals are able to socialize, communicate effectively, empathize well, and display social reciprocity with most other autistic individuals. This theory and subsequent findings challenge the commonly held belief that the social skills of autistic individuals are inherently impaired, as well as the theory of "mind-blindness" proposed by prominent autism researcher Simon Baron-Cohen in the mid-1980s, which suggested that empathy and theory of mind are universally impaired in autistic individuals.

There is currently no evidence of a cure for autism. The degree of symptoms can decrease, occasionally to the extent that people lose their diagnosis of autism; this occurs sometimes after intensive treatment and sometimes not. It is not known how often this outcome happens, with reported rates in unselected samples ranging from 3% to 25%. Although core difficulties tend to persist, symptoms often become less severe with age. Acquiring language before age six, having an IQ above 50, and having a marketable skill all predict better outcomes; independent living is unlikely in autistic people with higher support needs.