The St. Imier Congress was a meeting of the Jura Federation and anti-authoritarian apostates of the First International in September 1872. [1]

The St. Imier Congress was a meeting of the Jura Federation and anti-authoritarian apostates of the First International in September 1872. [1]

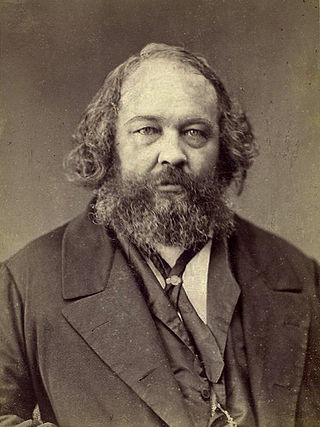

Among the ideological debates within the socialist First International, Karl Marx and Mikhail Bakunin disagreed on the revolutionary role of the working class and political struggle. Following the demise of the 1871 Paris Commune, the International debated whether the proletariat should create its own state (Marx's position) or continue making commune attempts (Bakunin's position). [2] Marx arranged the International's 1872 Congress in The Hague, the Netherlands, where Bakunin could not attend without arrest in Germany or France. [3] The Hague Congress sided with Marx [2] and expelled Bakunin from the International over aspects of his dissent and person, causing a split that would ultimately end the organization. [4]

International delegates of the minority opposed to Bakunin's expulsion met early in the September 1872 Hague Congress, in which 16 delegates (Spanish, Belgian, Dutch, Jurassic, and some American and French) privately decided to band together as anti-authoritarians. [5] Before the vote, they presented a signed Minority Declaration, in which they expressed that the Congress's business ran counter to their represented countries' principles. They wished to remain administrative contact and maintain federative autonomy within the International in lieu of splitting it. [6] Following the Hague Congress, anti-authoritarian minority delegates traveled to Brussels and issued a statement that they would not recognize the Congress's proceedings. They considered the circumstances around Bakunin's expulsion as unjust and encouraged anti-authoritarian federations to protest. The group continued on to Switzerland, where some met with Bakunin in Zurich. [7]

Earlier, in late August, the Italian Federation and Jura Federation began to plan an international alternative congress in Switzerland. The Italians and Errico Malatesta arrived in Zurich during the Hague Congress. They were joined by Andrea Costa and The Hague delegates Adhémar Schwitzguébel, Carlo Cafiero, and those from Spain. Bakunin presented his drafts for an Alliance organization to serve allied delegates in the International, but few took the effort seriously. [1]

The international alternative congress met in St. Imier on September 14 and 15, 1872. The group of 16 included Bakunin, the Zurich group, and a Russian group from Zurich. [8] Prior to the international congress, Schwitzguébel read a report. The group then resolved to reject as unjust the Hague Congress and its General Council's authoritarianism. A second resolution upheld the honor of the expelled Bakunin and Guillaume, and recognized the two within the Jura International. [9]

The alternative congress followed these proceedings. In four groups, the delegates wrote resolutions on September 15 and 16. All four of the resolutions were passed unanimously on the 16th. [9]

Its first resolution held that the Hague Congress majority's sole intent was to make the International more authoritarian, and resolved to reject that Congress's resolutions and the authority of its new General Council. The second resolution, the St. Imier pact, was a "pact of friendship, solidarity, and mutual defense" joining all interested federations against the General Council's authoritarian interests. The third resolution condemned the Hague Congress's advocacy for a singular path to proletariat social emancipation. It declared that the proletariat's first duty is to destroy all political power, rejected political organization (even temporary) towards this end as even more dangerous than contemporary governments, and advocated for uncompromising solidarity between proletarians internationally. The resolutions were bolder in language than the Hague Congress's Minority Declaration, likely on account of Bakunin's presence. [10]

The St. Imier Congress delegates included: [9]

Italian Federation Jura Federation | Spanish Federation French sections American sections |

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, social anarchist, and collectivist anarchist traditions. Bakunin's prestige as a revolutionary also made him one of the most famous ideologues in Europe, gaining substantial influence among radicals throughout Russia and Europe.

The International Workers' Association – Asociación Internacional de los Trabajadores (IWA–AIT) is an international federation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions and initiatives.

The Hague Congress was the fifth congress of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), held from 2–7 September 1872 in The Hague, the Netherlands.

The Jura Federation represented the anarchist, Bakuninist faction of the First International during the anti-statist split from the organization. Jura, a Swiss area, was known for its watchmaker artisans in La Chaux-de-Fonds, who shared anti-state, egalitarian views on work and social emancipation. The Jura Federation formed between international socialist congresses in 1869 and 1871. When the First International's General Council, led by Marxists, suppressed the Bakuninists, the Jura Federation organized an international of the disaffected federations at the 1872 St. Imier Congress. The congress disavowed the General Council's authoritarian consolidation of power and planning as an affront to the International's loose, federalist founding to support workers' emancipation. Members of the First International agreed and even statists joined the anti-statists' resulting Anti-authoritarian International, but by 1876, the alliance had mostly dissolved. While in decline, the Jura Federation remained the home of Bakuninists whose figures engaged on a two-decade debate on the merits of propaganda of the deed. The egalitarian relations of the Jura Federation had played an important role in Peter Kropotkin's adoption of anarchism, who became the anarchist standard-bearer after Bakunin.

James Guillaume (1844–1916) was a leading member of the Jura federation, the anarchist wing of the First International. Later, Guillaume would take an active role in the founding of the Anarchist St. Imier International.

The Anarchist International of St. Imier was an international workers' organization formed in 1872 after the split in the First International between the anarchists and the Marxists. This followed the 'expulsions' of Mikhail Bakunin and James Guillaume from the First International at the Hague Congress. It attracted some affiliates of the First International, repudiated the Hague resolutions, and adopted a Bakuninist programme, and lasted until 1877.

The International Alliance of Socialist Democracy was an organisation founded by Mikhail Bakunin along with 79 other members on October 28, 1868, as an organisation within the International Workingmen's Association (IWA). The establishment of the Alliance as a section of the IWA was not accepted by the general council of the IWA because, according to the IWA statutes, international organisations were not allowed to join, since the IWA already fulfilled the role of an international organisation. The Alliance dissolved shortly afterwards and the former members instead joined their respective national sections of the IWA.

Anarchism in France can trace its roots to thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who grew up during the Restoration and was the first self-described anarchist. French anarchists fought in the Spanish Civil War as volunteers in the International Brigades. According to journalist Brian Doherty, "The number of people who subscribed to the anarchist movement's many publications was in the tens of thousands in France alone."

The Ligue internationale de la paix was created after a public opinion campaign against a war between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia over Luxembourg. The Luxembourg crisis was peacefully resolved in 1867 by the Treaty of London but in 1870 the Franco-Prussian War could not be prevented so the league dissolved and refounded as the 'Société française pour l'arbitrage entre nations' in the same year.

The Petroleum Revolution was a libertarian and syndicalist leaning workers' revolution that took place in Alcoy, Alicante, Spain in 1873. The event is called the Petroleum Revolution since the workers, desperate due to living conditions, carried as their standard petroleum-soaked torches. During those days, according to chroniclers, the city stank of petroleum.

Over the past 150 years, anarchists, anarcho-syndicalists and libertarian socialists have held many congresses, conferences and international meetings in which trade unions, other groups and individuals have participated.

Rafael Farga i Pellicer was a Catalan anarcho-syndicalist who led the establishment of the Spanish Regional Federation of the IWA (FRE-AIT). As a print worker, he became involved in the Barcelona workers' movement following the Glorious Revolution of 1868, when he was first introduced to anarchism by the Italian anarchist Giuseppe Fanelli. He then set about organising the Catalan workers' movement along anarchist lines, emphasising decentralisation and federalism, eventually affiliating the FRE-AIT with Mikhail Bakunin's Anti-Authoritarian International. He then came to uphold the precepts of anarcho-syndicalism, overseeing the establishment of the FRE-AIT's successor, the Federation of Workers of the Spanish Region (FTRE). Later in life, he lost interest in syndicalist organising and turned to journalism, penning a series of studies of political figures and movements of the 19th century.

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions of political, social, and labour organizations and may also include rallies, marches, boycotts, civil disobedience, non-payment of taxes, and other forms of direct or indirect action. Additionally, general strikes might exclude care workers, such as teachers, doctors, and nurses.

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued the work of the dissolved First International, though excluding the powerful anarcho-syndicalist movement. While the international had initially declared its opposition to all warfare between European powers, most of the major European parties ultimately chose to support their respective states in World War I. After splitting into pro-Allied, pro-Central Powers, and antimilitarist factions, the international ceased to function. After the war, the remaining factions of the international went on to found the Labour and Socialist International, the International Working Union of Socialist Parties, and the Communist International.

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trade unions that were based on the working class and class struggle. It was founded in 1864 in a workmen's meeting held in St. Martin's Hall, London. Its first congress was held in 1866 in Geneva.

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolution is a necessary precondition for transitioning from a capitalist to a socialist mode of production. Revolution is not necessarily defined as a violent insurrection; it is defined as a seizure of political power by mass movements of the working class so that the state is directly controlled or abolished by the working class as opposed to the capitalist class and its interests.

Collectivist anarchism, also called anarchist collectivism and anarcho-collectivism, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates the abolition of both the state and private ownership of the means of production. In their place, it envisions both the collective ownership of the means of production and the entitlement of workers to the fruits of their own labour, which would be ensured by a societal pact between individuals and collectives. Collectivists considered trade unions to be the means through which to bring about collectivism through a social revolution, where they would form the nucleus for a post-capitalist society.

The Spanish Regional Federation of the International Workingmen's Association, known by its Spanish abbreviation FRE-AIT, was the Spanish chapter of the socialist working class organization commonly known today as the First International. The FRE-AIT was active between 1870 and 1881 and was influential not only in the labour movement of Spain, but also in the emerging global anarchist school of thought.

Anarchism in Switzerland appeared, as a political current, within the Jura Federation of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), under the influence of Mikhail Bakunin and Swiss libertarian activists such as James Guillaume and Adhémar Schwitzguébel. Swiss anarchism subsequently evolved alongside the nascent social democratic movement and participated in the local opposition to fascism during the interwar period. The contemporary Swiss anarchist movement then grew into a number of militant groups, libertarian socialist organizations and squats.

The Córdoba Congress was the Third Congress of the Spanish Regional Federation of the International Workingmen's Association (FRE-AIT). It was held in Córdoba between December 25, 1872 and January 3, 1873, just one month before King Amadeo I abdicated and the First Spanish Republic was subsequently proclaimed. Like what happened in the Hague Congress of 1872, the definitive rupture between anarchists, the majority, and Marxists, the minority, who no longer attended the Congress, was confirmed.