The French Quarter, also known as the Vieux Carré, is the oldest neighborhood in the city of New Orleans. After New Orleans was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the city developed around the Vieux Carré, a central square. The district is more commonly called the French Quarter today, or simply "The Quarter", related to changes in the city with American immigration after the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Most of the extant historic buildings were constructed either in the late 18th century, during the city's period of Spanish rule, or were built during the first half of the 19th century, after U.S. purchase and statehood.

Bourbon Street is a historic street in the heart of the French Quarter of New Orleans. Extending thirteen blocks from Canal Street to Esplanade Avenue, Bourbon Street is famous for its many bars and strip clubs.

Fort de Chartres was a French fortification first built in 1720 on the east bank of the Mississippi River in present-day Illinois. It was used as the administrative center for the province, which was part of New France. Due generally to river floods, the fort was rebuilt twice, the last time in limestone in the 1750s in the era of French colonial control over Louisiana and the Illinois Country.

The history of New Orleans, Louisiana traces the city's development from its founding by the French in 1718 through its period of Spanish control, then briefly back to French rule before being acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. During the War of 1812, the last major battle was the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. Throughout the 19th century, New Orleans was the largest port in the Southern United States, exporting most of the nation's cotton output and other farm products to Western Europe and New England. As the largest city in the South at the start of the Civil War (1861–1865), it was an early target for capture by Union forces. With its rich and unique cultural and architectural heritage, New Orleans remains a major destination for live music, tourism, conventions, and sporting events and annual Mardi Gras celebrations. After the significant destruction and loss of life resulting from Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the city would bounce back and rebuild in the ensuing years.

The Cathedral-Basilica of Saint Louis, King of France, also called St. Louis Cathedral, is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans and is the oldest cathedral in continuous use in the United States alongside the Royal Presidio Chapel in Monterey, California. It is dedicated to Saint Louis, also known as King Louis IX of France. The first church on the site was built in 1718; the third, under the Spanish rule, built in 1789, was raised to cathedral rank in 1793. The second St. Louis Cathedral was burned during the great fire of 1788 and was expanded and largely rebuilt and completed in the 1850s, with little of the 1789 structure remaining.

Louisiana or French Louisiana was an administrative district of New France. In 1682 French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle erected a cross near the mouth of the Mississippi River and claimed the whole of the drainage basin of the Mississippi River in the name of King Louis XIV, naming it "Louisiana". This land area stretched from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and from the Appalachian Mountains to the Rocky Mountains. The area was under French control from 1682 to 1762 and in part from 1801 (nominally) to 1803.

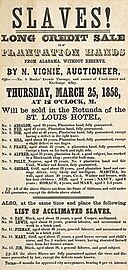

The Omni Royal Orleans is a 345-room hotel on the corner of St. Louis and Royal Streets near Jackson Square in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana. It was constructed in 1960 as The Royal Orleans Hotel, on the site of the old St. Louis Hotel, which was completely destroyed in the 1915 New Orleans hurricane. Earlier the site had been The City Exchange, a slave auction site until the 1830s.

Jackson Square, formerly the Place d'Armes (French) or Plaza de Armas (Spanish), is a historic park in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960, for its central role in the city's history, and as the site where in 1803 Louisiana was made United States territory pursuant to the Louisiana Purchase. In 2012 the American Planning Association designated Jackson Square as one of the Great Public Spaces in the United States.

Royal Street is a street in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. It is one of the original streets of the city, dating from the early 18th century, and is known today for its antique shops, art galleries, and hotels.

French colonial architecture includes several styles of architecture used by the French during colonization. Many former French colonies, especially those in Southeast Asia, have previously been reluctant to promote their colonial architecture as an asset for tourism; however, in recent times, the new generation of local authorities has somewhat "embraced" the architecture and has begun to advertise it. French Colonial architecture has a long history, beginning in North America in 1604 and being most active in the Western Hemisphere until the 19th century, when the French turned their attention more to Africa, Asia, and the Pacific.

Louisiana, or the Province of Louisiana, was a province of New Spain from 1762 to 1801 primarily located in the center of North America encompassing the western basin of the Mississippi River plus New Orleans. The area had originally been claimed and controlled by France, which had named it La Louisiane in honor of King Louis XIV in 1682. Spain secretly acquired the territory from France near the end of the Seven Years' War by the terms of the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762). The actual transfer of authority was a slow process, and after Spain finally attempted to fully replace French authorities in New Orleans in 1767, French residents staged an uprising which the new Spanish colonial governor did not suppress until 1769. Spain also took possession of the trading post of St. Louis and all of Upper Louisiana in the late 1760s, though there was little Spanish presence in the wide expanses of what they called the "Illinois Country".

The buildings and architecture of New Orleans reflect its history and multicultural heritage, from Creole cottages to historic mansions on St. Charles Avenue, from the balconies of the French Quarter to an Egyptian Revival U.S. Customs building and a rare example of a Moorish revival church.

The Hermann–Grima House is a historic house museum in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. The meticulously restored home reflects 19th century New Orleans. It is a Federal-style mansion with courtyard garden, built in 1831. It has the only extant horse stable and 1830s open-hearth kitchen in the French Quarter.

Madame John's Legacy is a historic house museum at 632 Dumaine Street in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana. Completed in 1788, it is one of the oldest houses in the French Quarter, and was built in the older French colonial style, rather than the more current Spanish colonial style of that time. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1970 for its architectural significance. The Louisiana State Museum owns the house and provides tours.

Theatre de la Rue Saint Pierre or Le Spectacle de la Rue Saint Pierre, was the first (French-speaking) theatre in New Orleans in Louisiana, active in 1792-1810. It opened in 1792 and was known to the Spanish-speaking citizens as El Coliseo and to the French-speaking citizens, La Salle Comedie. It was described as a small building of native lumber near the center of the city. It was located on the uptown side of St. Peter Street between Royal and Bourbon Streets, in what is now called the French Quarter.

Micaela Leonarda Antonia de Almonester Rojas y de la Ronde, Baroness de Pontalba was a wealthy New Orleans-born Creole aristocrat, businesswoman, and real estate designer and developer, who endures as one of the most recalled and dynamic personalities in the city's history, though she lived most of her life in Paris.

Exchange Place, also known as Exchange Alley and Exchange Passage, is a pedestrian zone that was created in 1831 originally as a small street in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana. Its original name was Passage de la Bourse, or Exchange Passage. The street was commissioned by the banker and merchant Samuel Jarvis Peters, who thought to build an exchange closer to Canal Street. It was built in coherence with the Merchants' Exchange Building on Royal Street as it acted as a back entrance. The street has been a hidden alleyway to many shops and restaurants over the years.

The Hotel St. Pierre is a collection of Creole cottages, many dating from the early 1780s, in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S.A. Its business address is 911 Burgundy Street.

The history of St. Louis, Missouri from 1763 to 1803 was marked by the transfer of French Louisiana to Spanish control, the founding of the city of St. Louis, its slow growth and role in the American Revolution under the rule of the Spanish, the transfer of the area to American control in the Louisiana Purchase, and its steady growth and prominence since then.

The Historic Cemeteries of New Orleans, New Orleans, United States, are a group of forty-two cemeteries that are historically and culturally significant. These are distinct from most cemeteries commonly located in the United States in that they are an amalgam of the French, Spanish, and Caribbean historical influences on the city of New Orleans in addition to limitations resulting from the city's high water table. The cemeteries reflect the ethnic, religious, and socio-economic heritages of the city. Architecturally, they are predominantly above ground tombs, family tombs, civic association tombs, and wall vaults, often in neo-classical design and laid out in regular patterns similar to city streets. They are at times referred to colloquially as “Cities of the Dead”, and some of the historic cemeteries are tourist destinations.