A watch is a portable timepiece intended to be carried or worn by a person. It is designed to keep a consistent movement despite the motions caused by the person's activities. A wristwatch is designed to be worn around the wrist, attached by a watch strap or other type of bracelet, including metal bands, leather straps, or any other kind of bracelet. A pocket watch is designed for a person to carry in a pocket, often attached to a chain.

Clockwork refers to the inner workings of either mechanical devices called clocks and watches or other mechanisms that work similarly, using a series of gears driven by a spring or weight.

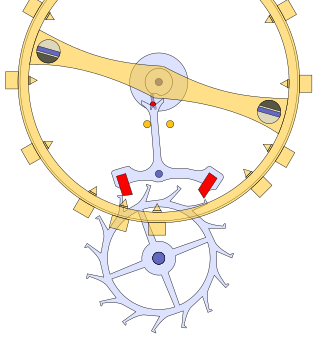

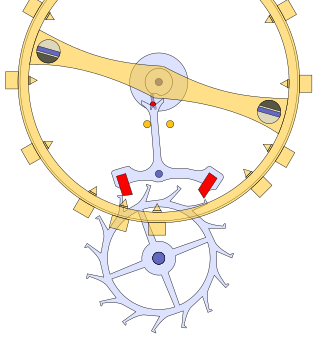

An escapement is a mechanical linkage in mechanical watches and clocks that gives impulses to the timekeeping element and periodically releases the gear train to move forward, advancing the clock's hands. The impulse action transfers energy to the clock's timekeeping element to replace the energy lost to friction during its cycle and keep the timekeeper oscillating. The escapement is driven by force from a coiled spring or a suspended weight, transmitted through the timepiece's gear train. Each swing of the pendulum or balance wheel releases a tooth of the escapement's escape wheel, allowing the clock's gear train to advance or "escape" by a fixed amount. This regular periodic advancement moves the clock's hands forward at a steady rate. At the same time, the tooth gives the timekeeping element a push, before another tooth catches on the escapement's pallet, returning the escapement to its "locked" state. The sudden stopping of the escapement's tooth is what generates the characteristic "ticking" sound heard in operating mechanical clocks and watches.

A pocket watch is a watch that is made to be carried in a pocket, as opposed to a wristwatch, which is strapped to the wrist.

In horology, a movement, also known as a caliber or calibre, is the mechanism of a watch or timepiece, as opposed to the case, which encloses and protects the movement, and the face, which displays the time. The term originated with mechanical timepieces, whose clockwork movements are made of many moving parts. The movement of a digital watch is more commonly known as a module.

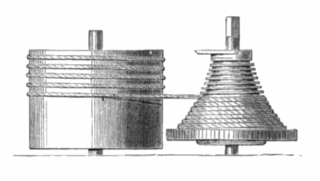

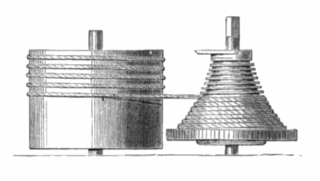

Used in mechanical watches and clocks, a barrel is a cylindrical metal box closed by a cover, with a ring of gear teeth around it, containing a spiral spring called the mainspring, which provides power to run the timepiece. The barrel turns on an arbor (axle). The spring is hooked to the barrel at its outer end and to the arbor at its inner end. The barrel teeth engage the first pinion of the wheel train of the watch, usually the center wheel. Barrels rotate slowly: for a watch mainspring barrel, the rate is usually one rotation every 8 hours. This construction allows the mainspring to be wound without interrupting the tension of the spring driving the timepiece.

A mainspring is a spiral torsion spring of metal ribbon—commonly spring steel—used as a power source in mechanical watches, some clocks, and other clockwork mechanisms. Winding the timepiece, by turning a knob or key, stores energy in the mainspring by twisting the spiral tighter. The force of the mainspring then turns the clock's wheels as it unwinds, until the next winding is needed. The adjectives wind-up and spring-powered refer to mechanisms powered by mainsprings, which also include kitchen timers, metronomes, music boxes, wind-up toys and clockwork radios.

The vergeescapement is the earliest known type of mechanical escapement, the mechanism in a mechanical clock that controls its rate by allowing the gear train to advance at regular intervals or 'ticks'. Verge escapements were used from the late 13th century until the mid 19th century in clocks and pocketwatches. The name verge comes from the Latin virga, meaning stick or rod.

A balance wheel, or balance, is the timekeeping device used in mechanical watches and small clocks, analogous to the pendulum in a pendulum clock. It is a weighted wheel that rotates back and forth, being returned toward its center position by a spiral torsion spring, known as the balance spring or hairspring. It is driven by the escapement, which transforms the rotating motion of the watch gear train into impulses delivered to the balance wheel. Each swing of the wheel allows the gear train to advance a set amount, moving the hands forward. The balance wheel and hairspring together form a harmonic oscillator, which due to resonance oscillates preferentially at a certain rate, its resonant frequency or "beat", and resists oscillating at other rates. The combination of the mass of the balance wheel and the elasticity of the spring keep the time between each oscillation or "tick" very constant, accounting for its nearly universal use as the timekeeper in mechanical watches to the present. From its invention in the 14th century until tuning fork and quartz movements became available in the 1960s, virtually every portable timekeeping device used some form of balance wheel.

The lever escapement, invented by the English clockmaker Thomas Mudge in 1754, is a type of escapement that is used in almost all mechanical watches, as well as small mechanical non-pendulum clocks, alarm clocks, and kitchen timers.

A striking clock is a clock that sounds the hours audibly on a bell, gong, or other audible device. In 12-hour striking, used most commonly in striking clocks today, the clock strikes once at 1:00 am, twice at 2:00 am, continuing in this way up to twelve times at 12:00 mid-day, then starts again, striking once at 1:00 pm, twice at 2:00 pm, up to twelve times at 12:00 midnight.

A fusee is a cone-shaped pulley with a helical groove around it, wound with a cord or chain attached to the mainspring barrel of antique mechanical watches and clocks. It was used from the 15th century to the early 20th century to improve timekeeping by equalizing the uneven pull of the mainspring as it ran down. Gawaine Baillie stated of the fusee, "Perhaps no problem in mechanics has ever been solved so simply and so perfectly."

A balance spring, or hairspring, is a spring attached to the balance wheel in mechanical timepieces. It causes the balance wheel to oscillate with a resonant frequency when the timepiece is running, which controls the speed at which the wheels of the timepiece turn, thus the rate of movement of the hands. A regulator lever is often fitted, which can be used to alter the free length of the spring and thereby adjust the rate of the timepiece.

The history of watches began in 16th-century Europe, where watches evolved from portable spring-driven clocks, which first appeared in the 15th century.

An automatic watch, also known as a self-winding watch or simply an automatic, is a mechanical watch where the natural motion of the wearer provides energy to wind the mainspring, making manual winding unnecessary if worn enough. It is distinguished from a manual watch in that a manual watch must have its mainspring wound by hand at regular intervals.

An electric clock is a clock that is powered by electricity, as opposed to a mechanical clock which is powered by a hanging weight or a mainspring. The term is often applied to the electrically powered mechanical clocks that were used before quartz clocks were introduced in the 1980s. The first experimental electric clocks were constructed around the 1840s, but they were not widely manufactured until mains electric power became available in the 1890s. In the 1930s, the synchronous electric clock replaced mechanical clocks as the most widely used type of clock.

In mechanical horology, a remontoire is a small secondary source of power, a weight or spring, which runs the timekeeping mechanism and is itself periodically rewound by the timepiece's main power source, such as a mainspring. It was used in a few precision clocks and watches to place the source of power closer to the escapement, thereby increasing the accuracy by evening out variations in drive force caused by unevenness of the friction in the geartrain. In spring-driven precision clocks, a gravity remontoire is sometimes used to replace the uneven force delivered by the mainspring running down by the more constant force of gravity acting on a weight. In turret clocks, it serves to separate the large forces needed to drive the hands from the modest forces needed to drive the escapement which keeps the pendulum swinging. A remontoire should not be confused with a maintaining power spring, which is used only to keep the timepiece going while it is being wound.

A mechanical watch is a watch that uses a clockwork mechanism to measure the passage of time, as opposed to quartz watches which function using the vibration modes of a piezoelectric quartz tuning fork, or radio watches, which are quartz watches synchronized to an atomic clock via radio waves. A mechanical watch is driven by a mainspring which must be wound either periodically by hand or via a self-winding mechanism. Its force is transmitted through a series of gears to power the balance wheel, a weighted wheel which oscillates back and forth at a constant rate. A device called an escapement releases the watch's wheels to move forward a small amount with each swing of the balance wheel, moving the watch's hands forward at a constant rate. The escapement is what makes the 'ticking' sound which is heard in an operating mechanical watch. Mechanical watches evolved in Europe in the 17th century from spring powered clocks, which appeared in the 15th century.

The history of timekeeping devices dates back to when ancient civilizations first observed astronomical bodies as they moved across the sky. Devices and methods for keeping time have gradually improved through a series of new inventions, starting with measuring time by continuous processes, such as the flow of liquid in water clocks, to mechanical clocks, and eventually repetitive, oscillatory processes, such as the swing of pendulums. Oscillating timekeepers are used in all modern timepieces.

In horology, a wheel train is the gear train of a mechanical watch or clock. Although the term is used for other types of gear trains, the long history of mechanical timepieces has created a traditional terminology for their gear trains which is not used in other applications of gears.