The north and south celestial poles are the two points in the sky where Earth's axis of rotation, indefinitely extended, intersects the celestial sphere. The north and south celestial poles appear permanently directly overhead to observers at Earth's North Pole and South Pole, respectively. As Earth spins on its axis, the two celestial poles remain fixed in the sky, and all other celestial points appear to rotate around them, completing one circuit per day.

In astronomy, axial precession is a gravity-induced, slow, and continuous change in the orientation of an astronomical body's rotational axis. In the absence of precession, the astronomical body's orbit would show axial parallelism. In particular, axial precession can refer to the gradual shift in the orientation of Earth's axis of rotation in a cycle of approximately 26,000 years. This is similar to the precession of a spinning top, with the axis tracing out a pair of cones joined at their apices. The term "precession" typically refers only to this largest part of the motion; other changes in the alignment of Earth's axis—nutation and polar motion—are much smaller in magnitude.

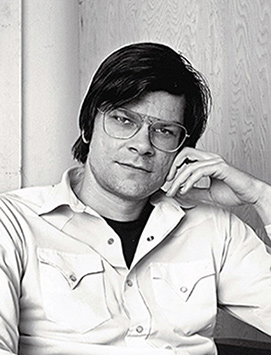

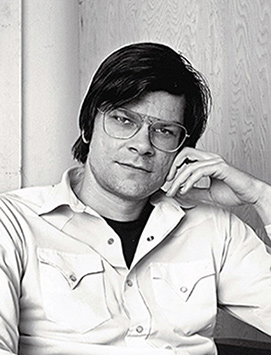

Robert Smithson was an American artist known for sculpture and land art who often used drawing and photography in relation to the spatial arts. His work has been internationally exhibited in galleries and museums and is held in public collections. He was one of the founders of the land art movement whose best known work is the Spiral Jetty (1970).

The Holland Tunnel is a vehicular tunnel under the Hudson River that connects the New York City neighborhood of Hudson Square in Lower Manhattan to the east with Jersey City in New Jersey to the west. The tunnel is operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and carries Interstate 78; the New Jersey side is also designated the eastern terminus of Route 139. The Holland Tunnel is one of three vehicular crossings between Manhattan and New Jersey; the two others are the Lincoln Tunnel and George Washington Bridge.

Land art, variously known as Earth art, environmental art, and Earthworks, is an art movement that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, largely associated with Great Britain and the United States but that also includes examples from many countries. As a trend, "land art" expanded boundaries of art by the materials used and the siting of the works. The materials used were often the materials of the Earth, including the soil, rocks, vegetation, and water found on-site, and the sites of the works were often distant from population centers. Though sometimes fairly inaccessible, photo documentation was commonly brought back to the urban art gallery.

A pole star or polar star is a star, preferably bright, nearly aligned with the axis of a rotating astronomical body.

Artforum is an international monthly magazine specializing in contemporary art. The magazine is distinguished from other magazines by its unique 10½ x 10½ inch square format, with each cover often devoted to the work of an artist. Notably, the Artforum logo is a bold and condensed iteration of the Akzidenz-Grotesk font, a feat for an American publication to have considering how challenging it was to obtain fonts favored by the Swiss school via local European foundries in the 1960s.

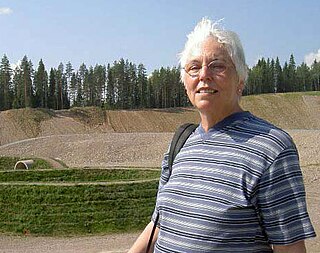

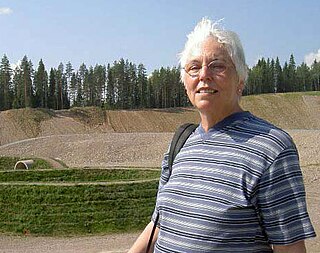

Nancy Holt was an American artist most known for her public sculpture, installation art, concrete poetry, and land art. Throughout her career, Holt also produced works in other media, including film and photography, and wrote books and articles about art.

Polar alignment is the act of aligning the rotational axis of a telescope's equatorial mount or a sundial's gnomon with a celestial pole to parallel Earth's axis.

Jeffrey Lynn Koons is an American artist recognized for his work dealing with popular culture and his sculptures depicting everyday objects, including balloon animals produced in stainless steel with mirror-finish surfaces. He lives and works in both New York City and his hometown of York, Pennsylvania. His works have sold for substantial sums, including at least two record auction prices for a work by a living artist: US$58.4 million for Balloon Dog (Orange) in 2013 and US$91.1 million for Rabbit in 2019.

Marin Yvonne Ireland is an American actress. Known for her work in theatre and independent films, The New York Times deemed Ireland "one of the great drama queens of the New York stage". Her accolades include a Theatre World Award and nominations for an Independent Spirit Award and a Tony Award.

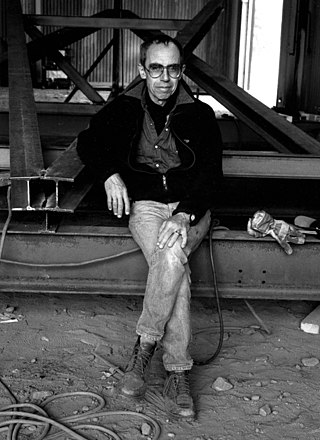

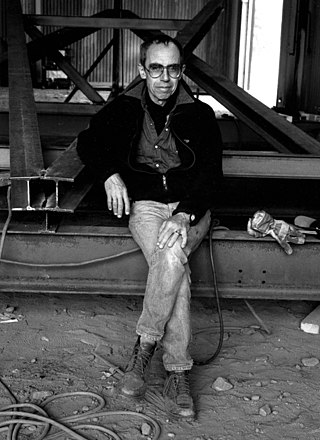

Charles Ross is an American contemporary artist known for work centered on natural light, time and planetary motion. His practice spans several art modalities and includes large-scale prism and solar spectrum installations, "solar burns" created by focusing sunlight through lenses, paintings made with dynamite and powdered pigment, and Star Axis, an earthwork built to observe the stars. Ross emerged in the mid-1960s at the advent of minimalism, and is considered a forerunner of "prism art"—a sub-tradition within that movement—as well as one of the major figures of land art. His work employs geometry, seriality, refined forms and surfaces, and scientific concepts in order to reveal optical, astronomical and perceptual phenomena. Artforum critic Dan Beachy-Quick wrote that "math as a manifestation of fundamental cosmic laws—elegance, order, beauty—is a principle undergirding Ross’s work … [he] becomes a maker-medium of a kind, constructing various methods for sun and star to create the art itself."

Virginia Dwan was an American art collector, art patron, philanthropist, and founder of the Dwan Light Sanctuary in Montezuma, New Mexico. She was the former owner and executive director of Dwan Gallery, Los Angeles (1959–1967) and Dwan Gallery New York (1965–1971), a contemporary art gallery closely identified with the American movements of Minimalism, Conceptual Art, and Earthworks.

Sarah Oppenheimer is a New York City-based artist whose projects explore the articulations and experience of built space. Her work involves precise transformations of architecture that disrupt, subvert or shuffle visitors' visual and bodily experience. Artforum critic Jeffrey Kastner wrote that Oppenheimer's artworks "typically induce a certain kind of vaguely vertiginous, almost giddy uncertainty" that over time turns "indeterminacies of apprehension into epistemological uncertainties, epistemic puzzlement into ontological perplexity."

Charles McGill was an artist based in Peekskill, New York.

Olga Viso is a Cuban American curator of modern and contemporary art and a museum director based at Arizona State University's Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts in Tempe, Arizona. She served as executive director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota from 2007 through 2017, and was curator of contemporary art and director of the Smithsonian Institution's Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC from 1995-2007.

Sarah Nicole Prickett is a writer, art critic and editor. She was the founder and editor of Adult, an arts and criticism magazine that launched in 2013.

The John Gibson Gallery was a contemporary art gallery in New York City, in operation from November 1967 to 2000, and founded by John Gibson. Early on, the gallery specialized in selling contemporary monumental–sized sculptures.

Derrick Adams is an American visual and performance artist and curator. Much of Adams' work is centered around his Black identity, frequently referencing patterns, images, and themes of Black culture in America. Adams has additionally worked as a fine art professor, serving as a faculty member at Maryland Institute College of Art.

Cristos Gianakos is an American postminimalist artist known for his large-scale ramp sculptures and installations. He lives and works in New York, where he has been teaching at the School of Visual Arts since 1963.