The two images

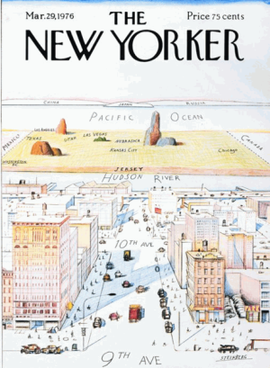

The subject of the controversy was a drawing by Steinberg known as View of the World from 9th Avenue or A Parochial New Yorker's View of the World. The drawing, which appeared on the cover of the March 29, 1976 issue of The New Yorker, depicts four city blocks of Manhattan in great detail, with the rest of the United States and the world sketched sparsely in the background. The horizon is marked by a red line, and a thin blue wash of color at the top denotes the sky. At the top is the name of the magazine, in its characteristic font.

The New Yorker registered the image with the United States Copyright Office and assigned the copyright to Steinberg. About three months later, the magazine made an agreement to print and sell posters of the image.

The Moscow on the Hudson poster featured the movie's lead actor Robin Williams and his two co-stars at the bottom of the frame, with a highly detailed depiction of four city blocks of Manhattan behind them. In the background is a blue stripe representing the Atlantic Ocean, three landmarks denoting cities in Europe, and a set of Russian-looking buildings labeled "Moscow". Again, the horizon is marked by a red line, and the sky by a thin blue wash of color. At the top is the name of the movie, in the same font used by The New Yorker. The poster image was published as an advertisement in many newspapers across the country.

Defenses

The court held that the Moscow on the Hudson poster was not a parody because it was not meant to satirize the Steinberg image itself, but merely satirized the same concept of the parochial New Yorker that was parodied by Steinberg's work. Because the copyrighted work was not an object of the parody, the appropriation of the image was not fair use.

The defendants also argued that Steinberg was estopped from defending his copyright on the grounds that he had taken no action over a period of eight years to stop others from counterfeiting his posters and adapting his idea to other locations, and had not acted in response to newspaper ads promoting the movie. The court rejected this argument, holding that the defendants had not proved any of the elements of estoppel: (1) a representation in fact; (2) reasonable reliance thereon; and (3) injury or damage resulting from denial by the party making the representation. While the defendants argued that Steinberg had made a representation of his acquiescence to their use of his image in the movie poster by not complaining about the ads in the newspaper, the judge rejected this line of reasoning and noted that the defendants had continued to use the infringing advertisements even after becoming aware of Steinberg's objections. Further, there was no existing relationship between the parties that could give rise to estoppel.

Finally, the defendants claimed the affirmative defense of laches, asserting that Steinberg had waited over six months to complain to Columbia Pictures about the alleged infringement in order to increase his award in the eventual lawsuit. The court dismissed this allegation on the grounds that Steinberg had registered his complaint with the defendants within weeks of beginning their advertising campaign, and that a six-month delay between publication of the allegedly infringing work and instigation of a lawsuit was not sufficient to establish a claim of laches.

Fair use is a doctrine in United States law that permits limited use of copyrighted material without having to first acquire permission from the copyright holder. Fair use is one of the limitations to copyright intended to balance the interests of copyright holders with the public interest in the wider distribution and use of creative works by allowing as a defense to copyright infringement claims certain limited uses that might otherwise be considered infringement. Unlike "fair dealing" rights that exist in most countries that were part of the British Empire in the 20th century, the fair use right is a general exception that applies to all different kinds of uses with all types of works and turns on a flexible proportionality test that examines the purpose of the use, the amount used, and the impact on the market of the original work.

In common-law legal systems, laches is a lack of diligence and activity in making a legal claim, or moving forward with legal enforcement of a right, particularly in regard to equity. This means that it is an unreasonable delay that can be viewed as prejudicing the opposing party. When asserted in litigation, it is an equity defense, that is, a defense to a claim for an equitable remedy.

An affirmative defense to a civil lawsuit or criminal charge is a fact or set of facts other than those alleged by the plaintiff or prosecutor which, if proven by the defendant, defeats or mitigates the legal consequences of the defendant's otherwise unlawful conduct. In civil lawsuits, affirmative defenses include the statute of limitations, the statute of frauds, waiver, and other affirmative defenses such as, in the United States, those listed in Rule 8 (c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. In criminal prosecutions, examples of affirmative defenses are self defense, insanity, entrapment and the statute of limitations.

Itar-Tass Russian News Agency v. Russian Kurier, Inc., 153 F.3d 82, was a copyright case about the Russian language weekly Russian Kurier in New York City that had copied and published various materials from Russian newspapers and news agency reports of Itar-TASS. The case was ultimately decided by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. The decision was widely commented upon and the case is considered a landmark case because the court defined rules applicable in the U.S. on the extent to which the copyright laws of the country of origin or those of the U.S. apply in international disputes over copyright. The court held that to determine whether a claimant actually held the copyright on a work, the laws of the country of origin usually applied, but that to decide whether a copyright infringement had occurred and for possible remedies, the laws of the country where the infringement was claimed applied.

Harper & Row v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539 (1985), was a United States Supreme Court decision in which public interest in learning about a historical figure's impressions of a historic event was held not to be sufficient to show fair use of material otherwise protected by copyright. Defendant, The Nation, had summarized and quoted substantially from A Time to Heal, President Gerald Ford's forthcoming memoir of his decision to pardon former president Richard Nixon. When Harper & Row, who held the rights to A Time to Heal, brought suit, The Nation asserted that its use of the book was protected under the doctrine of fair use, because of the great public interest in a historical figure's account of a historic incident. The Court rejected this argument holding that the right of first publication was important enough to find in favor of Harper.

View of the World from 9th Avenue is a 1976 illustration by Saul Steinberg that served as the cover of the March 29, 1976, edition of The New Yorker. The work presents the view from Manhattan of the rest of the world showing Manhattan as the center of the world.

In United States copyright law, transformative use or transformation is a type of fair use that builds on a copyrighted work in a different manner or for a different purpose from the original, and thus does not infringe its holder's copyright. Transformation is an important issue in deciding whether a use meets the first factor of the fair-use test, and is generally critical for determining whether a use is in fact fair, although no one factor is dispositive.

Castle Rock Entertainment Inc. v. Carol Publishing Group, 150 F.3d 132, was a U.S. copyright infringement case involving the popular American sitcom Seinfeld. Some U.S. copyright law courses use the case to illustrate modern application of the fair use doctrine. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld a lower court's summary judgment that the defendant had committed copyright infringement. The decision is noteworthy for classifying Seinfeld trivia not as unprotected facts, but as protectable expression. The court also rejected the defendant's fair use defense finding that any transformative purpose posse, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994).

Copyright in architecture is an important, but little understood subject in the architectural discipline. Copyright is a legal concept that gives the creator of a work the exclusive right to use that work for a limited time. These rights can be an important mechanism through which architects can protect their designs.

Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp. 2d 191, was a decision by the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, which ruled that exact photographic copies of public domain images could not be protected by copyright in the United States because the copies lack originality. Even though accurate reproductions might require a great deal of skill, experience and effort, the key element to determine whether a work is copyrightable under US law is originality.

In copyright law, a derivative work is an expressive creation that includes major copyrightable elements of a first, previously created original work. The derivative work becomes a second, separate work independent in form from the first. The transformation, modification or adaptation of the work must be substantial and bear its author's personality sufficiently to be original and thus protected by copyright. Translations, cinematic adaptations and musical arrangements are common types of derivative works.

Fair dealing is a limitation and exception to the exclusive rights granted by copyright law to the author of a creative work. Fair dealing is found in many of the common law jurisdictions of the Commonwealth of Nations.

The copyright law of the United States grants monopoly protection for "original works of authorship". With the stated purpose to promote art and culture, copyright law assigns a set of exclusive rights to authors: to make and sell copies of their works, to create derivative works, and to perform or display their works publicly. These exclusive rights are subject to a time and generally expire 70 years after the author's death or 95 years after publication. In the United States, works published before January 1, 1928, are in the public domain.

Analytic dissection is a concept in U.S. copyright law analysis of computer software. Analytic dissection is a tool for determining whether a work accused of copyright infringement is substantially similar to a copyright-protected work.

The Abstraction-Filtration-Comparison test (AFC) is a method of identifying substantial similarity for the purposes of applying copyright law. In particular, the AFC test is used to determine whether non-literal elements of a computer program have been copied by comparing the protectable elements of two programs. The AFC test was developed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1992 in its opinion for Computer Associates Int. Inc. v. Altai Inc. It has been widely adopted by United States courts and recognized by courts outside the United States as well.

Playboy Enterprises, Inc. v. Starware Publishing Corp. 900 F.Supp. 433 was a case heard before the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida in May 1995. The case revolved around the subject of copyright infringement and exclusive rights in copyrighted works. Plaintiff Playboy Enterprises filed a motion for partial summary judgment of liability of copyright infringement against defendant Starware Publishing Corporation. Specifically, Playboy Enterprises ("PEI") argued that Starware's distribution of 53 of Playboy's images, taken from an online bulletin board, and then sold on a CD-ROM, infringed upon PEI's copyrights. The case affirmed that it was copyright infringement, granting Playboy Enterprises the partial summary judgment. Most importantly, the case established that "The copyright owner need not prove knowledge or intent on the part of the defendant to establish liability for direct copyright infringement."

Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley, Ltd., 448 F.3d 605, is a 2006 case of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit regarding fair use of images in a pictorial history text. It affirmed the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, which held at trial that the publisher's use of several images of past Grateful Dead concert posters and tickets, reduced considerably, in a timeline of the band's history was a sufficiently transformative use.

Wolk v. Kodak Imaging Network, Inc., 840 F. Supp. 2d 724, was a United States district court case in which the visual artist Sheila Wolk brought suit against Kodak Imaging Network, Inc., Eastman Kodak Company, and Photobucket.com, Inc. for copyright infringement. Users uploaded Wolk's work to Photobucket, a user-generated content provider, which had a revenue sharing agreement with Kodak that permitted users to use Kodak Gallery to commercially print (photofinish) images from Photobucket's site—including unauthorized copies of Wolk's artwork.

Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., 572 U.S. 663 (2014), is a United States Supreme Court copyright decision in which the Court held 6-3 that the equitable defense of laches is not available to copyright defendants in claims for damages.

Copyright protection is available to the creators of a range of works including literary, musical, dramatic and artistic works. Recognition of fictional characters as works eligible for copyright protection has come about with the understanding that characters can be separated from the original works they were embodied in and acquire a new life by featuring in subsequent works.