Vanity is the excessive belief in one's own abilities or attractiveness to others. Prior to the 14th century, it did not have such narcissistic undertones, and merely meant futility. The related term vainglory is now often seen as an archaic synonym for vanity, but originally meant considering one's own capabilities and that God's help was not needed, i.e. unjustified boasting; although glory is now seen as having a predominantly positive meaning, the Latin term from which it derives, gloria, roughly means boasting, and was often used as a negative criticism.

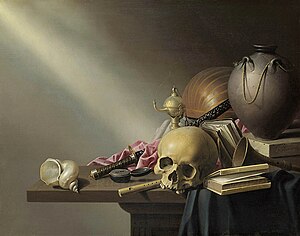

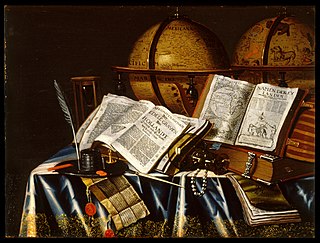

Vanitas is a genre of art which uses symbolism to show the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death. The paintings involved still life imagery of transitory items. The genre began in the 16th century and continued into the 17th century. Vanitas art is a type of allegorical art representing a higher ideal. It was a sub-genre of painting heavily employed by Dutch painters during the Baroque period (c.1585–1730). Spanish painters working at the end of the Spanish Golden Age also created vanitas paintings.

Maria van Oosterwijck, also spelled Oosterwyck, (1630–1693) was a Dutch Golden Age painter, specializing in richly detailed flower paintings and other still lifes.

A Lady Writing a Letter is an oil on canvas painting attributed to 17th century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. It is believed to have been completed by artist during his mature phase, in the mid-to-late 1660s. The work is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Nicolaes van Verendael or Nicolaes van Veerendael was a Flemish painter active in Antwerp who is mainly known for his flower paintings and vanitas still lifes. He was a frequent collaborator of other Antwerp artists to whose compositions he added the still life elements. He also painted a number of singeries, i.e., scenes with monkeys dressed and acting as humans.

Harmen Steenwijck or Harmen Steenwyck was a Dutch Golden Age painter who specialised in still life painting, especially in the style of Dutch vanitas.

Hendrick Andriessen, known as Mancken Heyn was a Flemish still-life painter. He is known for his vanitas still lifes, which are made up of objects referencing the precariousness of life, and 'smoker' still lifes, which depict smoking utensils. The artist worked in Antwerp and likely also in the Dutch Republic.

Hendrik Gerritsz Pot was a Dutch Golden Age painter, who lived and painted in Haarlem, where he was an officer of the militia, or schutterij. Dutch artist Frans Hals painted Pot in militia sash in Hals' The Officers of the St Adrian Militia Company in 1633. Pot is the man reading a book on the far right.

David Bailly (1584–1657) was a Dutch Golden Age artist known for his still-life paintings, portraits, and self-portraits.

Joris van Son or Georg van Son was a Flemish still life painter who worked in a number of sub-genres but is principally known for his still lifes of fruit. He also painted flowers, banquets, vanitas still lifes and pronkstillevens. He is known to have painted fish still lifes representing the Four Elements, and also collaborated with figure artists on 'garland paintings', which typically represent a devotional image framed by a fruit or flower garland.

Cornelis van der Meulen or Cornelis Vermeulen, was a Dutch painter who after training in the Dutch Republic had a career in Sweden where he became a court painter. He is known for still lifes of flowers and game, trompe-l'œil and vanitas still lifes, topographical views and portraits.

Skull symbolism is the attachment of symbolic meaning to the human skull. The most common symbolic use of the skull is as a representation of death.

Franciscus Gijsbrechts, was a Flemish painter of still lifes specialised in vanitas still lifes and trompe-l'œil paintings. He worked in the second half of the seventeenth century in the Spanish Netherlands, Denmark and the Dutch Republic. Like his father, he painted trompe-l'œil still lifes, a still life genre that uses illusionistic means to create the appearance that the painted, two-dimensional composition is actually a three-dimensional, real object.

Pieter Steenwijck, was a Dutch Golden Age painter.

Catarina Ykens or Catarina Ykens (I) (née Floquet) (1608/1618 – after 1666) was a Flemish still life painter. She is known for flower and fruit garland paintings and vanitas paintings.

Joannes de Cordua or Johann de Cordua was a Flemish painter who was mainly active in Vienna and Prague. He is known for his still lifes, peasant scenes, portraits, and biblical themes.

Godfriedt van Bochoutt (fl 1659–1666 was a Flemish still painter who was active in his native Bruges and Rotterdam. The limited body of work attributed to him ranges from fruit still lifes, hunting still lifes, vanitas still lifes and trompe l'oeil paintings.

Carel Fonteyn or Carel Fontyn was a Flemish painter active in Antwerp. He is known for his Vanitas still lifes with flowers, skulls and other Vanitas symbols.

Still Life with Books is a c. 1627–1628 oil-on-panel painting by Dutch artist Jan Lievens. The painting is an example of the Dutch vanitas genre and an example of Dutch realism. The painting was privately owned until it was purchased by the Rijksmuseum in 1963. For many years experts thought it was the work of Rembrandt.

Still Life of Fruit and Dead Fowl or A Stoneware jug, Fruit, and Dead Game Birds is a c. 1650 oil-on-panel still-life painting by the Dutch Golden Age painter Harmen Steenwijck. It features dead birds which are meant to represent mortality and fruits which are meant to convey wealth. These place it between the "ontbijt", and explicit vanitas pieces.