A superorganism, or supraorganism, [1] is a group of synergetically-interacting organisms of the same species. A community of synergetically-interacting organisms of different species is called a holobiont.

A superorganism, or supraorganism, [1] is a group of synergetically-interacting organisms of the same species. A community of synergetically-interacting organisms of different species is called a holobiont.

The term superorganism is used most often to describe a social unit of eusocial animals in which division of labour is highly specialised and individuals cannot survive by themselves for extended periods. Ants are the best-known example of such a superorganism. A superorganism can be defined as "a collection of agents which can act in concert to produce phenomena governed by the collective", [2] phenomena being any activity "the hive wants" such as ants collecting food and avoiding predators, [3] [4] or bees choosing a new nest site. [5] In challenging environments, micro organisms collaborate and evolve together to process unlikely sources of nutrients such as methane. This process called syntrophy ("eating together") might be linked to the evolution of eukaryote cells and involved in the emergence or maintenance of life forms in challenging environments on Earth and possibly other planets. [6] Superorganisms tend to exhibit homeostasis, power law scaling, persistent disequilibrium and emergent behaviours. [7]

The term was coined in 1789 by James Hutton, the "father of geology", to refer to Earth in the context of geophysiology. The Gaia hypothesis of James Lovelock, [8] and Lynn Margulis as well as the work of Hutton, Vladimir Vernadsky and Guy Murchie, have suggested that the biosphere itself can be considered a superorganism, but that has been disputed. [9] This view relates to systems theory and the dynamics of a complex system.

The concept of a superorganism raises the question of what is to be considered an individual. Toby Tyrrell's critique of the Gaia hypothesis argues that Earth's climate system does not resemble an animal's physiological system. Planetary biospheres are not tightly regulated in the same way that animal bodies are: "planets, unlike animals, are not products of evolution. Therefore we are entitled to be highly skeptical (or even outright dismissive) about whether to expect something akin to a 'superorganism'". He concludes that "the superorganism analogy is unwarranted [9]

Some scientists have suggested that individual human beings can be thought of as "superorganisms"; [10] as a typical human digestive system contains 1013 to 1014 microorganisms whose collective genome, the microbiome studied by the Human Microbiome Project, contains at least 100 times as many genes as the human genome itself. [11] [12] Salvucci wrote that superorganism is another level of integration that is observed in nature. These levels include the genomic, the organismal and the ecological levels. The genomic structure of organisms reveals the fundamental role of integration and gene shuffling along evolution. [13]

The 19th-century thinker Herbert Spencer coined the term super-organic to focus on social organization (the first chapter of his Principles of Sociology is entitled "Super-organic Evolution" [14] ), though this was apparently a distinction between the organic and the social, not an identity: Spencer explored the holistic nature of society as a social organism while distinguishing the ways in which society did not behave like an organism. [15] For Spencer, the super-organic was an emergent property of interacting organisms, that is, human beings. And, as has been argued by D. C. Phillips, there is a "difference between emergence and reductionism". [16]

The economist Carl Menger expanded upon the evolutionary nature of much social growth but never abandoned methodological individualism. Many social institutions arose, Menger argued, not as "the result of socially teleological causes, but the unintended result of innumerable efforts of economic subjects pursuing 'individual' interests". [17]

Both Spencer and Menger argued that because individuals choose and act, any social whole should be considered less than an organism, but Menger emphasized that more strongly. Spencer used the organistic idea to engage in extended analysis of social structure and conceded that it was primarily an analogy. For Spencer, the idea of the super-organic best designated a distinct level of social reality above that of biology and psychology, not a one-to-one identity with an organism. Nevertheless, Spencer maintained that "every organism of appreciable size is a society", which has suggested to some that the issue may be terminological. [18]

The term superorganic was adopted by the anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber in 1917. [19] Social aspects of the superorganism concept are analysed by Alan Marshall in his 2002 book "The Unity of Nature". [20] Finally, recent work in social psychology has offered the superorganism metaphor as a unifying framework to understand diverse aspects of human sociality, such as religion, conformity, and social identity processes. [21]

Superorganisms are important in cybernetics, particularly biocybernetics, since they are capable of the so-called "distributed intelligence", a system composed of individual agents that have limited intelligence and information. [22] They can pool resources and so can complete goals that are beyond reach of the individuals on their own. [22] Existence of such behavior in organisms has many implications for military and management applications and is being actively researched. [22]

Superorganisms are also considered dependent upon cybernetic governance and processes. [23] This is based on the idea that a biological system – in order to be effective – needs a sub-system of cybernetic communications and control. [24] This is demonstrated in the way a mole rat colony uses functional synergy and cybernetic processes together. [25]

Joël de Rosnay also introduced a concept called "cybionte" to describe cybernetic superorganism. [26] The notion associates superorganism with chaos theory, multimedia technology, and other new developments.

In biology, a colony is composed of two or more conspecific individuals living in close association with, or connected to, one another. This association is usually for mutual benefit such as stronger defense or the ability to attack bigger prey.

Herbert Spencer was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in Principles of Biology (1864) after reading Charles Darwin's 1859 book On the Origin of Species. The term strongly suggests natural selection, yet Spencer saw evolution as extending into realms of sociology and ethics, so he also supported Lamarckism.

Sociocybernetics is an interdisciplinary science between sociology and general systems theory and cybernetics. The International Sociological Association has a specialist research committee in the area – RC51 – which publishes the (electronic) Journal of Sociocybernetics.

Second-order cybernetics, also known as the cybernetics of cybernetics, is the recursive application of cybernetics to itself and the reflexive practice of cybernetics according to such a critique. It is cybernetics where "the role of the observer is appreciated and acknowledged rather than disguised, as had become traditional in western science". Second-order cybernetics was developed between the late 1960s and mid 1970s by Heinz von Foerster and others, with key inspiration coming from Margaret Mead. Foerster referred to it as "the control of control and the communication of communication" and differentiated first order cybernetics as "the cybernetics of observed systems" and second-order cybernetics as "the cybernetics of observing systems".

Francis Paul Heylighen is a Belgian cyberneticist investigating the emergence and evolution of intelligent organization. He presently works as a research professor at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, where he directs the transdisciplinary "Center Leo Apostel" and the research group on "Evolution, Complexity and Cognition". He is best known for his work on the Principia Cybernetica Project, his model of the Internet as a global brain, and his contributions to the theories of memetics and self-organization. He is also known, albeit to a lesser extent, for his work on gifted people and their problems.

Engineering cybernetics also known as technical cybernetics or cybernetic engineering, is the branch of cybernetics concerned with applications in engineering, in fields such as control engineering and robotics.

Biocybernetics is the application of cybernetics to biological science disciplines such as neurology and multicellular systems. Biocybernetics plays a major role in systems biology, seeking to integrate different levels of information to understand how biological systems function. The field of cybernetics itself has origins in biological disciplines such as neurophysiology. Biocybernetics is an abstract science and is a fundamental part of theoretical biology, based upon the principles of systemics. Biocybernetics is a psychological study that aims to understand how the human body functions as a biological system and performs complex mental functions like thought processing, motion, and maintaining homeostasis.(PsychologyDictionary.org)Within this field, many distinct qualities allow for different distinctions within the cybernetic groups such as humans and insects such as beehives and ants. Humans work together but they also have individual thoughts that allow them to act on their own, while worker bees follow the commands of the queen bee. . Although humans often work together, they can also separate from the group and think for themselves.(Gackenbach, J. 2007) A unique example of this within the human sector of biocybernetics would be in society during the colonization period, when Great Britain established their colonies in North America and Australia. Many of the traits and qualities of the mother country were inherited by the colonies, as well as niche qualities that were unique to them based on their areas like language and personality—similar vines and grasses, where the parent plant produces offshoots, spreading from the core. Once the shoots grow their roots and get separated from the mother plant, they will survive independently and be considered their plant. Society is more closely related to plants than to animals since, like plants, there is no distinct separation between parent and offspring. The branching of society is more similar to plant reproduction than to animal reproduction. Humans are a k- selected species that typically have fewer offspring that they nurture for longer periods than r -selected species. It could be argued that when Britain created colonies in regions like North America and Australia, these colonies, once they became independent, should be seen as offspring of British society. Like all children, the colonies inherited many characteristics, such as language, customs and technologies, from their parents, but still developed their own personality. This form of reproduction is most similar to the type of vegetative reproduction used by many plants, such as vines and grasses, where the parent plant produces offshoots, spreading ever further from the core. When such a shoot, once it has produced its own roots, gets separated from the mother plant, it will survive independently and define a new plant. Thus, the growth of society is more like that of plants than like that of the higher animals that we are most familiar with, there is not a clear distinction between a parent and its offspring. Superorganisms are also capable of the so-called "distributed intelligence," a system composed of individual agents with limited intelligence and information. These can pool resources to complete goals beyond the individuals' reach on their own. Similar to the concept of "Game theory." In this concept, individuals and organisms make choices based on the behaviors of the other player to deem the most profitable outcome for them as an individual rather than a group.

Joan Roughgarden is an American ecologist and evolutionary biologist. She has engaged in theory and observation of coevolution and competition in Anolis lizards of the Caribbean, and recruitment limitation in the rocky intertidal zones of California and Oregon. She has more recently become known for her rejection of sexual selection, her theistic evolutionism, and her work on holobiont evolution.

Social organism is a sociological concept, or model, wherein a society or social structure is regarded as a "living organism". The various entities comprising a society, such as law, family, crime, etc., are examined as they interact with other entities of the society to meet its needs. Every entity of a society, or social organism, has a function in helping maintain the organism's stability and cohesiveness.

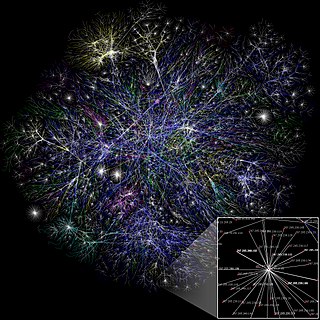

The global brain is a neuroscience-inspired and futurological vision of the planetary information and communications technology network that interconnects all humans and their technological artifacts. As this network stores ever more information, takes over ever more functions of coordination and communication from traditional organizations, and becomes increasingly intelligent, it increasingly plays the role of a brain for the planet Earth. In the philosophy of mind, global brain finds an analog in Averroes's theory of the unity of the intellect

Living systems are life forms treated as a system. They are said to be open self-organizing and said to interact with their environment. These systems are maintained by flows of information, energy and matter. Multiple theories of living systems have been proposed. Such theories attempt to map general principles for how all living systems work.

Microbiota are the range of microorganisms that may be commensal, mutualistic, or pathogenic found in and on all multicellular organisms, including plants. Microbiota include bacteria, archaea, protists, fungi, and viruses, and have been found to be crucial for immunologic, hormonal, and metabolic homeostasis of their host.

An organism is any biological living system that functions as an individual life form. It has been a common belief that all organisms are composed of cells. The idea of organism is based on the concept of minimal functional unit of life. Three traits have been proposed to play the main role in qualification as an organism:

Eusociality, is the highest level of organization of sociality. It is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative brood care, overlapping generations within a colony of adults, and a division of labor into reproductive and non-reproductive groups. The division of labor creates specialized behavioral groups within an animal society which are sometimes referred to as 'castes'. Eusociality is distinguished from all other social systems because individuals of at least one caste usually lose the ability to perform behaviors characteristic of individuals in another caste. Eusocial colonies can be viewed as superorganisms.

Cybernetics is a field of systems theory that studies circular causal systems whose outputs are also inputs, such as feedback systems. It is concerned with the general principles of circular causal processes, including in ecological, technological, biological, cognitive and social systems and also in the context of practical activities such as designing, learning, and managing.

The hologenome theory of evolution recasts the individual animal or plant as a community or a "holobiont" – the host plus all of its symbiotic microbes. Consequently, the collective genomes of the holobiont form a "hologenome". Holobionts and hologenomes are structural entities that replace misnomers in the context of host-microbiota symbioses such as superorganism, organ, and metagenome. Variation in the hologenome may encode phenotypic plasticity of the holobiont and can be subject to evolutionary changes caused by selection and drift, if portions of the hologenome are transmitted between generations with reasonable fidelity. One of the important outcomes of recasting the individual as a holobiont subject to evolutionary forces is that genetic variation in the hologenome can be brought about by changes in the host genome and also by changes in the microbiome, including new acquisitions of microbes, horizontal gene transfers, and changes in microbial abundance within hosts. Although there is a rich literature on binary host–microbe symbioses, the hologenome concept distinguishes itself by including the vast symbiotic complexity inherent in many multicellular hosts. For recent literature on holobionts and hologenomes published in an open access platform, see the following reference.

A holobiont is an assemblage of a host and the many other species living in or around it, which together form a discrete ecological unit through symbiosis, though there is controversy over this discreteness. The components of a holobiont are individual species or bionts, while the combined genome of all bionts is the hologenome. The holobiont concept was initially introduced by the German theoretical biologist Adolf Meyer-Abich in 1943, and then apparently independently by Dr. Lynn Margulis in her 1991 book Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation. The concept has evolved since the original formulations. Holobionts include the host, virome, microbiome, and any other organisms which contribute in some way to the functioning of the whole. Well-studied holobionts include reef-building corals and humans.

Hologenomics is the omics study of hologenomes. A hologenome is the whole set of genomes of a holobiont, an organism together with all co-habitating microbes, other life forms, and viruses. While the term hologenome originated from the hologenome theory of evolution, which postulates that natural selection occurs on the holobiont level, hologenomics uses an integrative framework to investigate interactions between the host and its associated species. Examples include gut microbe or viral genomes linked to human or animal genomes for host-microbe interaction research. Hologenomics approaches have also been used to explain genetic diversity in the microbial communities of marine sponges.

Since the colonization of land by ancestral plant lineages 450 million years ago, plants and their associated microbes have been interacting with each other, forming an assemblage of species that is often referred to as a holobiont. Selective pressure acting on holobiont components has likely shaped plant-associated microbial communities and selected for host-adapted microorganisms that impact plant fitness. However, the high microbial densities detected on plant tissues, together with the fast generation time of microbes and their more ancient origin compared to their host, suggest that microbe-microbe interactions are also important selective forces sculpting complex microbial assemblages in the phyllosphere, rhizosphere, and plant endosphere compartments.

The holobiont concept is a renewed paradigm in biology that can help to describe and understand complex systems, like the host-microbe interactions that play crucial roles in marine ecosystems. However, there is still little understanding of the mechanisms that govern these relationships, the evolutionary processes that shape them and their ecological consequences. The holobiont concept posits that a host and its associated microbiota with which it interacts, form a holobiont, and have to be studied together as a coherent biological and functional unit to understand its biology, ecology, and evolution.

If Col. Thorpe [of the US DARPA] has his way, the four divisions of the US military and hundreds of industrial subcontractors will become a single interconnected superorganism. The immediate step to this world of distributed intelligence is an engineering protocol developed by a consortium of defense simulation centers in Orlando Florida ...