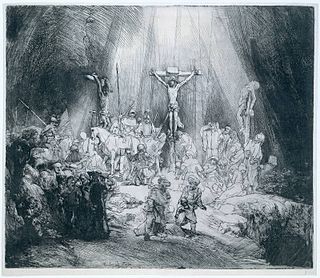

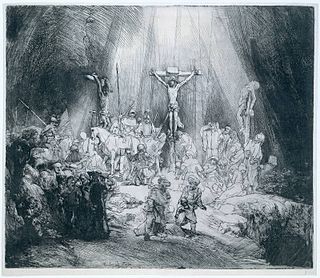

Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types of material. As a method of printmaking, it is, along with engraving, the most important technique for old master prints, and remains in wide use today. In a number of modern variants such as microfabrication etching and photochemical milling it is a crucial technique in much modern technology, including circuit boards.

Printmaking is the process of creating artworks by printing, normally on paper, but also on fabric, wood, metal, and other surfaces. "Traditional printmaking" normally covers only the process of creating prints using a hand processed technique, rather than a photographic reproduction of a visual artwork which would be printed using an electronic machine ; however, there is some cross-over between traditional and digital printmaking, including risograph. Except in the case of monotyping, all printmaking processes have the capacity to produce identical multiples of the same artwork, which is called a print. Each print produced is considered an "original" work of art, and is correctly referred to as an "impression", not a "copy". However, impressions can vary considerably, whether intentionally or not. Master printmakers are technicians who are capable of printing identical "impressions" by hand. Historically, many printed images were created as a preparatory study, such as a drawing. A print that copies another work of art, especially a painting, is known as a "reproductive print".

Mezzotint is a monochrome printmaking process of the intaglio family. It was the first printing process that yielded half-tones without using line- or dot-based techniques like hatching, cross-hatching or stipple. Mezzotint achieves tonality by roughening a metal plate with thousands of little dots made by a metal tool with small teeth, called a "rocker". In printing, the tiny pits in the plate retain the ink when the face of the plate is wiped clean. This technique can achieve a high level of quality and richness in the print.

Drypoint is a printmaking technique of the intaglio family, in which an image is incised into a plate with a hard-pointed "needle" of sharp metal or diamond point. In principle, the method is practically identical to engraving. The difference is in the use of tools, and that the raised ridge along the furrow is not scraped or filed away as in engraving. Traditionally the plate was copper, but now acetate, zinc, or plexiglas are also commonly used. Like etching, drypoint is easier to master than engraving for an artist trained in drawing because the technique of using the needle is closer to using a pencil than the engraver's burin.

Aquatint is an intaglio printmaking technique, a variant of etching that produces areas of tone rather than lines. For this reason it has mostly been used in conjunction with etching, to give both lines and shaded tone. It has also been used historically to print in colour, both by printing with multiple plates in different colours, and by making monochrome prints that were then hand-coloured with watercolour.

Collagraphy is a printmaking process introduced in 1955 by Glen Alps in which materials are applied to a rigid substrate. The word is derived from the Greek word koll or kolla, meaning glue, and graph, meaning the activity of drawing.

Relief printing is a family of printing methods where a printing block, plate or matrix- which has had ink applied to its non-recessed surface- is brought into contact with paper. The non-recessed surface will leave ink on the paper, whereas the recessed areas will not. A printing press may not be needed, as the back of the paper can be rubbed or pressed by hand with a simple tool such as a brayer or roller. In contrast, in intaglio printing, the recessed areas are printed.

Photogravure is a process for printing photographs, also sometimes used for reproductive intaglio printmaking. It is a photo-mechanical process whereby a copper plate is grained and then coated with a light-sensitive gelatin tissue which had been exposed to a film positive, and then etched, resulting in a high quality intaglio plate that can reproduce detailed continuous tones of a photograph.

Intaglio is the family of printing and printmaking techniques in which the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink. It is the direct opposite of a relief print where the parts of the matrix that make the image stand above the main surface.

Monoprinting is a type of printmaking where the intent is to make unique prints, that may explore an image serially. Other methods of printmaking create editioned multiples, the monoprint is editioned as 1 of 1. There are many techniques of mono-printing, in particular the monotype. Printmaking techniques which can be used to make mono-prints include lithography, woodcut, and etching.

The etching revival was the re-emergence and invigoration of etching as an original form of printmaking during the period approximately from 1850 to 1930. The main centres were France, Britain and the United States, but other countries, such as the Netherlands, also participated. A strong collector's market developed, with the most sought-after artists achieving very high prices. This came to an abrupt end after the 1929 Wall Street crash wrecked what had become a very strong market among collectors, at a time when the typical style of the movement, still based on 19th-century developments, was becoming outdated.

Ernest Stephen Lumsden, was a distinguished painter, noted etcher and authority on etching.

Viscosity printing is a multi-color printmaking technique that incorporates principles of relief printing and intaglio printing. It was pioneered by Stanley William Hayter.

Steel engraving is a technique for printing illustrations based on steel instead of copper. It has been rarely used in artistic printmaking, although it was much used for reproductions in the 19th century. Steel engraving was introduced in 1792 by Jacob Perkins (1766–1849), an American inventor, for banknote printing. When Perkins moved to London in 1818, the technique was adapted in 1820 by Charles Warren and especially by Charles Heath (1785–1848) for Thomas Campbell's Pleasures of Hope, which contained the first published plates engraved on steel. The new technique only partially replaced the other commercial techniques of that time such as wood engraving, copper engraving and later lithography.

An old master print is a work of art produced by a printing process within the Western tradition. The term remains current in the art trade, and there is no easy alternative in English to distinguish the works of "fine art" produced in printmaking from the vast range of decorative, utilitarian and popular prints that grew rapidly alongside the artistic print from the 15th century onwards. Fifteenth-century prints are sufficiently rare that they are classed as old master prints even if they are of crude or merely workmanlike artistic quality. A date of about 1830 is usually taken as marking the end of the period whose prints are covered by this term.

The Disasters of War is a series of 82 prints created between 1810 and 1820 by the Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya (1746–1828). Although Goya did not make known his intention when creating the plates, art historians view them as a visual protest against the violence of the 1808 Dos de Mayo Uprising, the subsequent Peninsular War of 1808–1814 and the setbacks to the liberal cause following the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1814. During the conflicts between Napoleon's French Empire and Spain, Goya retained his position as first court painter to the Spanish crown and continued to produce portraits of the Spanish and French rulers. Although deeply affected by the war, he kept private his thoughts on the art he produced in response to the conflict and its aftermath.

Vitreography is a fine art printmaking technique that uses a 3⁄8-inch-thick (9.5 mm) float glass matrix instead of the traditional matrices of metal, wood or stone. A print created using the technique is called a vitreograph. Unlike a monotype, in which ink is painted onto a smooth glass plate and transferred to paper to produce a unique work, the vitreograph technique involves fixing the imagery in, or on, the glass plate. This allows the production of an edition of prints.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters or The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters is an aquatint by the Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya. Created between 1797 and 1799 for the Diario de Madrid, it is the 43rd of the 80 aquatints making up the satirical Los caprichos.

Stipple engraving is a technique used to create tone in an intaglio print by distributing a pattern of dots of various sizes and densities across the image. The pattern is created on the printing plate either in engraving by gouging out the dots with a burin, or through an etching process. Stippling was used as an adjunct to conventional line engraving and etching for over two centuries, before being developed as a distinct technique in the mid-18th century.

À la poupée is a largely historic intaglio printmaking technique for making colour prints by applying different ink colours to a single printing plate using ball-shaped wads of cloth, one for each colour. The paper has just one run through the press, but the inking needs to be carefully re-done after each impression is printed. Each impression will usually vary at least slightly, and sometimes very significantly.