Musicology is the scholarly study of music. Musicology research combines and intersects with many fields, including psychology, sociology, acoustics, neurology, natural sciences, formal sciences and computer science.

Franz Peter Schubert was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short life, Schubert left behind a vast oeuvre, including more than 600 secular vocal works, seven complete symphonies, sacred music, operas, incidental music, and a large body of piano and chamber music. His major works include the art songs "Erlkönig", "Gretchen am Spinnrade", "Ave Maria"; the Trout Quintet, the unfinished Symphony No. 8 in B minor, the "Great" Symphony No. 9 in C major, the String Quartet No. 14 Death and the Maiden, a String Quintet, the two sets of Impromptus for solo piano, the three last piano sonatas, the Fantasia in F minor for piano four hands, the opera Fierrabras, the incidental music to the play Rosamunde, and the song cycles Die schöne Müllerin, Winterreise and Schwanengesang.

Music history, sometimes called historical musicology, is a highly diverse subfield of the broader discipline of musicology that studies music from a historical point of view. In theory, "music history" could refer to the study of the history of any type or genre of music. In practice, these research topics are often categorized as part of ethnomusicology or cultural studies, whether or not they are ethnographically based. The terms "music history" and "historical musicology" usually refer to the history of the notated music of Western elites, sometimes called "art music".

Polytonality is the musical use of more than one key simultaneously. Bitonality is the use of only two different keys at the same time. Polyvalence or polyvalency is the use of more than one harmonic function, from the same key, at the same time.

Rosemary Isabel Brown was an English composer, pianist and spirit medium who claimed that dead composers dictated new musical works to her. She created a small media sensation in the 1970s by presenting works purportedly dictated to her by Claude Debussy, Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, Franz Schubert, Frédéric Chopin, Igor Stravinsky, Johann Sebastian Bach, Johannes Brahms, Ludwig van Beethoven, Robert Schumann and Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Program music or programmatic music is a type of instrumental art music that attempts to musically render an extramusical narrative. The narrative itself might be offered to the audience through the piece's title, or in the form of program notes, inviting imaginative correlations with the music. A well-known example is Sergei Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf.

New musicology is a wide body of musicology since the 1980s with a focus upon the cultural study, aesthetics, criticism, and hermeneutics of music. It began in part a reaction against the traditional positivist musicology—focused on primary research—of the early 20th century and postwar era. Many of the procedures of new musicology are considered standard, although the name more often refers to the historical turn rather than to any single set of ideas or principles. Indeed, although it was notably influenced by feminism, gender studies, queer theory, postcolonial studies, and critical theory, new musicology has primarily been characterized by a wide-ranging eclecticism.

In Western musical theory, a cadence is the end of a phrase in which the melody or harmony creates a sense of full or partial resolution, especially in music of the 16th century onwards. A harmonic cadence is a progression of two or more chords that concludes a phrase, section, or piece of music. A rhythmic cadence is a characteristic rhythmic pattern that indicates the end of a phrase. A cadence can be labeled "weak" or "strong" depending on the impression of finality it gives. While cadences are usually classified by specific chord or melodic progressions, the use of such progressions does not necessarily constitute a cadence—there must be a sense of closure, as at the end of a phrase. Harmonic rhythm plays an important part in determining where a cadence occurs. The word "cadence" sometimes slightly shifts its meaning depending on the context; for example, it can be used to refer to the last few notes of a particular phrase, or to just the final chord of that phrase, or to types of chord progressions that are suitable for phrase endings in general.

Absolute music is music that is not explicitly "about" anything; in contrast to program music, it is non-representational. The idea of absolute music developed at the end of the 18th century in the writings of authors of early German Romanticism, such as Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder, Ludwig Tieck and E. T. A. Hoffmann but the term was not coined until 1846 where it was first used by Richard Wagner in a programme to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.

The First Viennese School is a name mostly used to refer to three composers of the Classical period in Western art music in late-18th-century to early-19th-century Vienna: Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven. Sometimes, Franz Schubert is added to the list.

The String Quartet No. 13 in A minor, D 804, Op. 29, was written by Franz Schubert between February and March 1824. It dates roughly to the same time as his monumental Death and the Maiden Quartet, emerging around three years after his previous attempt to write for the string quartet genre, the Quartettsatz, D 703, that he never finished.

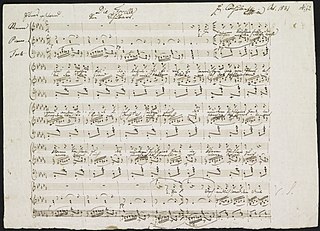

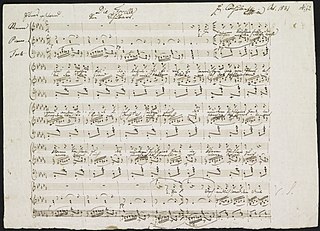

"Die Forelle", Op. 32, D 550. is a lied, or song, composed in early 1817 for solo voice and piano with music by the Austrian composer Franz Schubert (1797–1828). Schubert chose to set the text of a poem by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, first published in the Schwäbischer Musenalmanach in 1783. The full poem tells the story of a trout being caught by a fisherman, but in its final stanza reveals its purpose as a moral piece warning young women to guard against young men. When Schubert set the poem to music, he removed the last verse, which contained the moral, changing the song's focus and enabling it to be sung by male or female singers. Schubert produced six subsequent copies of the work, all with minor variations.

Maynard Elliott Solomon was an American music executive and musicologist, a co-founder of Vanguard Records as well as a music producer. Later, he became known for his biographical studies of Viennese Classical composers, specifically Beethoven, Mozart (biography), and Schubert. Solomon was the first to propose the highly disputed theory of Schubert's homosexuality in a scholarly publication.

Susan Youens is the author of many books on German lieder. A musicologist, her work on Franz Schubert and Hugo Wolf is considered some of the most scholarly and useful material on these composers. Both musicologists and performers have often cited her work.

Lewis H. Lockwood is an American musicologist whose main fields are the music of the Italian Renaissance and the life and work of Ludwig van Beethoven. Joseph Kerman described him as "a leading musical scholar of the postwar generation, and the leading American authority on Beethoven".

Philip Brett was a British-born American musicologist, musician and conductor. He was particularly known for his scholarly studies on Benjamin Britten and William Byrd and for his contributions to the development of lesbian and gay musicology. At the time of his death, he was Distinguished Professor of Musicology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Rita Katherine Steblin was a musicologist, specializing in archival work combining music history, iconography and genealogical research.

Rose Rosengard Subotnik is a leading American musicologist, generally credited with introducing the writing of Theodor Adorno to English-speaking musicologists in the late 1970s.

Women in musicology describes the role of women professors, scholars and researchers in postsecondary education musicology departments at postsecondary education institutions, including universities, colleges and music conservatories. Traditionally, the vast majority of major musicologists and music historians have been men. Nevertheless, some women musicologists have reached the top ranks of the profession. Carolyn Abbate is an American musicologist who did her PhD at Princeton University. She has been described by the Harvard Gazette as "one of the world's most accomplished and admired music historians".

Birgit Lodes is a German musicologist and lecturer at the University of Vienna.