A grenadier was historically an assault-specialist soldier who threw hand grenades in siege operation battles. The distinct combat function of the grenadier was established in the mid-17th century, when grenadiers were recruited from among the strongest and largest soldiers. By the 18th century, the grenadier dedicated to throwing hand grenades had become a less necessary specialist, yet in battle, the grenadiers were the physically robust soldiers who led vanguard assaults, such as storming fortifications in the course of siege warfare.

The insurrection of 10 August 1792 was a defining event of the French Revolution, when armed revolutionaries in Paris, increasingly in conflict with the French monarchy, stormed the Tuileries Palace. The conflict led France to abolish the monarchy and establish a republic.

The Flight of the Wild Geese was the departure of an Irish Jacobite army under the command of Patrick Sarsfield from Ireland to France, as agreed in the Treaty of Limerick on 3 October 1691, following the end of the Williamite War in Ireland. More broadly, the term Wild Geese is used in Irish history to refer to Irish soldiers who left to serve in continental European armies in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.

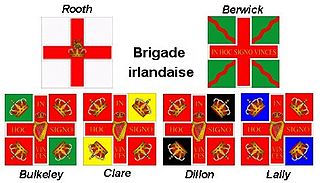

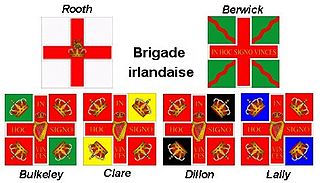

The Irish Brigade was a brigade in the French Royal Army composed of Irish exiles, led by Lord Mountcashel. It was formed in May 1690 when five Jacobite regiments were sent from Ireland to France in exchange for a larger force of French infantry who were sent to fight in the Williamite War in Ireland. The regiments comprising the Irish Brigade retained their special status as foreign units in the French Army until nationalised in 1791.

A royal guard is a group of military bodyguards, soldiers or armed retainers responsible for the protection of a royal family member, such as a king or queen, or prince or princess. They often are an elite unit of the regular armed forces, or are designated as such, and may maintain special rights or privileges.

The Russian Imperial Guard, officially known as the Leib Guard were military units serving as personal guards of the Emperor of Russia. Peter the Great founded the first such units in 1683, to replace the politically motivated Streltsy. The Imperial Guard subsequently increased in size and diversity to become an elite corps of all branches within the Imperial Army rather than Household troops in direct attendance on the Tsar. Numerous links were however maintained with the Imperial family and the bulk of the regiments of the Imperial Guard were stationed in and around Saint Petersburg in peacetime. The Imperial Guard was disbanded in 1917 following the Russian Revolution.

The French Guards were an elite infantry regiment of the French Royal Army. They formed a constituent part of the maison militaire du roi de France under the Ancien Régime.

The Women's March on Versailles, also known as the October March, the October Days or simply the March on Versailles, was one of the earliest and most significant events of the French Revolution. The march began among women in the marketplaces of Paris who, on the morning of 5 October 1789, were nearly rioting over the high price of bread. The unrest quickly became intertwined with the activities of revolutionaries seeking liberal political reforms and a constitutional monarchy for France. The market women and their allies ultimately grew into a crowd of thousands. Encouraged by revolutionary agitators, they ransacked the city armory for weapons and marched on the Palace of Versailles. The crowd besieged the palace and, in a dramatic and violent confrontation, they successfully pressed their demands upon King Louis XVI. The next day, the crowd forced the king and his family to return with them to Paris. Over the next few weeks most of the French Assembly also relocated to the capital.

A facing colour, also known as facings, is a common tailoring technique for European military uniforms where the visible inside lining of a standard military jacket, coat or tunic is of a different colour to that of the garment itself. The jacket lining evolved to be of different coloured material, then of specific hues. Accordingly, when the material was turned back on itself: the cuffs, lapels and tails of the jacket exposed the contrasting colours of the lining or facings, enabling ready visual distinction of different units: regiments, divisions or battalions each with their own specific and prominent colours. The use of distinctive facings for individual regiments was at its most popular in 18th century armies, but standardisation within infantry branches became more common during and after the Napoleonic Wars.

The Régiment de Royal Suédois was a foreign infantry regiment in the Royal French Army during the Ancien Régime. It was created in 1690 from Swedish prisoners taken during the Battle of Fleurus. The regiment eventually acquired the privilege of being called a Royal regiment.

The Cent-Suisses were an elite infantry company of Swiss mercenaries that served the French kings from 1471 to 1792 and from 1814 to 1830.

The Gardes du Corps du Roi was the senior formation of the King of France's household cavalry within the maison militaire du roi de France.

The Scottish Guards was a bodyguard unit founded in 1418 by the Valois Charles VII of France, to be personal bodyguards to the French monarchy. They were assimilated into the Maison du Roi and later formed the first company of the Garde du Corps du Roi.

The Walloon Guards were an infantry corps recruited for the Spanish Army in the region now known as Belgium, mainly from Catholic Wallonia. As foreign troops without direct ties amongst the Spanish population, the Walloons were often tasked with the maintenance of public order, eventually being incorporated as a regiment of the Spanish Royal Guard.

The Lion Monument, or the Lion of Lucerne, is a rock relief in Lucerne, Switzerland, designed by Bertel Thorvaldsen and hewn in 1820–21 by Lukas Ahorn. It commemorates the Swiss Guards who were massacred in 1792 during the French Revolution, when revolutionaries stormed the Tuileries Palace in Paris. It is one of the most famous monuments in Switzerland, visited annually by about 1.4 million tourists. In 2006, it was placed under Swiss monument protection.

The Constitutional Guard was a French royal guard formation which lasted a few months in 1792 as part of the Maison du Roi, being superseded by the National Guard. It existed in the period of the constitutional monarchy during the French Revolution.

The maison militaire du roi de France, in English the military household of the king of France, was the military part of the French royal household or Maison du Roi under the Ancien Régime. The term only appeared in 1671, though such a gathering of units pre-dates this. Like the rest of the royal household, the military household was under the authority of the Secretary of State for the Maison du Roi. Still, it depended on the ordinaire des guerres for its budget. Under Louis XIV, these two officers of state were given joint command of the military household.

The French Royal Army was the principal land force of the Kingdom of France. It served the Bourbon dynasty from the reign of Louis XIV in the mid-17th century to that of Charles X in the 19th, with an interlude from 1792 to 1814 and another during the Hundred Days in 1815. It was permanently dissolved following the July Revolution in 1830. The French Royal Army became a model for the new regimental system that was to be imitated throughout Europe from the mid-17th century onward. It was regarded as Europe's greatest military force for much of its existence.

The Cent-gardes Squadron, also called Cent Gardes à Cheval, was an elite cavalry squadron of the Second French Empire primarily responsible for protecting the person of the Emperor Napoleon III, as well as providing security within the Tuileries Palace. It also provided an escort for the emblems of the Imperial Guard and their award ceremony with flag and standard bearers.

The pantalon rouge were an integral part of the uniform of most regiments of the French army from 1829 to 1914. Some parts of the Kingdom of France's army already wore red trousers or breeches but the French Revolution saw the introduction of white trousers for infantrymen. Following the 1814 Bourbon Restoration white breeches or blue trousers were worn but red trousers for infantry were adopted in 1829 to encourage the French rose madder dye-growing industry. Madder red is a shade darker than the scarlet of British uniforms.