Tlaloc is the god of rain in Aztec religion. He was also a deity of earthly fertility and water, worshipped as a giver of life and sustenance. He was feared for his power over hail, thunder, lightning. He is also associated with caves, springs, and mountains, most specifically the sacred mountain where he was believed to reside. His followers were one of the oldest and most universal in ancient Mexico.

A chacmool is a form of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican sculpture depicting a reclining figure with its head facing 90 degrees from the front, supporting itself on its elbows and supporting a bowl or a disk upon its stomach. These figures possibly symbolised slain warriors carrying offerings to the gods; the bowl upon the chest was used to hold sacrificial offerings, including pulque, tamales, tortillas, tobacco, turkeys, feathers, and incense. In Aztec examples, the receptacle is a cuauhxicalli. Chacmools were often associated with sacrificial stones or thrones. The chacmool form of sculpture first appeared around the 9th century AD in the Valley of Mexico and the northern Yucatán Peninsula.

The Toltec culture was a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture that ruled a state centered in Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico, during the Epiclassic and the early Post-Classic period of Mesoamerican chronology, reaching prominence from 950 to 1150 CE. The later Aztec culture considered the Toltec to be their intellectual and cultural predecessors and described Toltec culture emanating from Tōllān[ˈtoːlːãːn̥] as the epitome of civilization. In the Nahuatl language the word Tōltēkatl[toːɬˈteːkat͡ɬ] (singular) or Tōltēkah[toːɬˈteːkaḁ] (plural) came to take on the meaning "artisan". The Aztec oral and pictographic tradition also described the history of the Toltec Empire, giving lists of rulers and their exploits.

The Aztecs were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Aztec culture was organized into city-states (altepetl), some of which joined to form alliances, political confederations, or empires. The Aztec Empire was a confederation of three city-states established in 1427: Tenochtitlan, city-state of the Mexica or Tenochca; Texcoco; and Tlacopan, previously part of the Tepanec empire, whose dominant power was Azcapotzalco. Although the term Aztecs is often narrowly restricted to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, it is also broadly used to refer to Nahua polities or peoples of central Mexico in the prehispanic era, as well as the Spanish colonial era (1521–1821). The definitions of Aztec and Aztecs have long been the topic of scholarly discussion ever since German scientist Alexander von Humboldt established its common usage in the early 19th century.

Tezcatlipoca was a central deity in Aztec religion. He is associated with a variety of concepts, including the night sky, hurricanes, obsidian, and conflict. He was considered one of the four sons of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, the primordial dual deity. His main festival was Toxcatl, which, like most religious festivals of Aztec culture, involved human sacrifice.

Huitzilopochtli is the solar and war deity of sacrifice in Aztec mythology. He was also the patron god of the Aztecs and their capital city, Tenochtitlan. He wielded Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, as a weapon, thus also associating Huitzilopochtli with fire.

In Aztec mythology, Centeōtl[senˈteoːt͡ɬ] is the maize deity. Cintli[ˈsint͡ɬi] means "dried maize still on the cob" and teōtl[ˈteoːt͡ɬ] means "deity". According to the Florentine Codex, Centeotl is the son of the earth goddess, Tlazolteotl and solar deity Piltzintecuhtli, the planet Mercury. He was born on the day-sign 1 Xochitl. Another myth claims him as the son of the goddess Xochiquetzal. The majority of evidence gathered on Centeotl suggests that he is usually portrayed as a young man, with yellow body colouration. Some specialists believe that Centeotl used to be the maize goddess Chicomecōātl. Centeotl was considered one of the most important deities of the Aztec era. There are many common features that are shown in depictions of Centeotl. For example, there often seems to be maize in his headdress. Another striking trait is the black line passing down his eyebrow, through his cheek and finishing at the bottom of his jaw line. These face markings are similarly and frequently used in the late post-classic depictions of the 'foliated' Maya maize god.

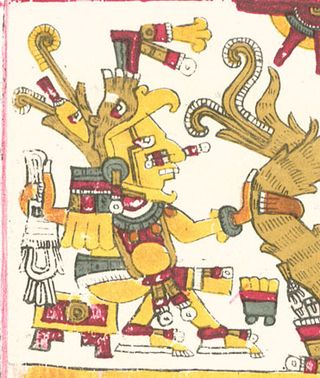

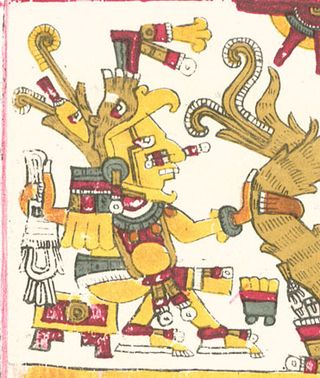

In Aztec mythology, Xiuhtecuhtli[ʃiʍˈtekʷt͡ɬi], was the god of fire, day and heat. In historical sources he is called by many names, which reflect his varied aspects and dwellings in the three parts of the cosmos. He was the lord of volcanoes, the personification of life after death, warmth in cold (fire), light in darkness and food during famine. He was also named Cuezaltzin[kʷeˈsaɬt͡sin] ("flame") and Ixcozauhqui[iʃkoˈsaʍki], and is sometimes considered to be the same as Huehueteotl, although Xiuhtecuhtli is usually shown as a young deity. His wife was Chalchiuhtlicue. Xiuhtecuhtli is sometimes considered to be a manifestation of Ometecuhtli, the Lord of Duality, and according to the Florentine Codex Xiuhtecuhtli was considered to be the father of the Gods, who dwelled in the turquoise enclosure in the center of earth. Xiuhtecuhtli-Huehueteotl was one of the oldest and most revered of the indigenous pantheon. The cult of the God of Fire, of the Year, and of Turquoise perhaps began as far back as the middle Preclassic period. Turquoise was the symbolic equivalent of fire for Aztec priests. A small fire was permanently kept alive at the sacred center of every Aztec home in honor of Xiuhtecuhtli.

In Aztec religion, Huixtocihuatl was a fertility goddess who presided over salt and salt water. The Aztecs considered her to be the older sister of the rain gods, including Tlaloc. Much of the information known about Huixtocihuatl and how the Aztecs celebrated her comes from Bernardino de Sahagún's manuscripts. His Florentine Codex explains how Huixtocihuatl became the salt god. It records that Huixtocihuatl angered her younger brothers by mocking them, so they banished her to the salt beds. It was there where she discovered salt and how it was created. As described in the second book of the Florentine Codex, during Tecuilhuitontli, the seventh month of the Aztec calendar, there was a festival in honor of Huixtocihuatl. The festival culminated with the sacrifice of Huixtocihuatl's ixiptla, the embodiment of the deity in human form.

Tlaltecuhtli is a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican deity worshipped primarily by the Mexica (Aztec) people. Sometimes referred to as the "earth monster," Tlaltecuhtli's dismembered body was the basis for the world in the Aztec creation story of the fifth and final cosmos. In carvings, Tlaltecuhtli is often depicted as an anthropomorphic being with splayed arms and legs. Considered the source of all living things, he had to be kept sated by human sacrifices which would ensure the continued order of the world.

In Aztec mythology, Xipe Totec or Xipetotec was a life-death-rebirth deity, god of agriculture, vegetation, the east, spring, goldsmiths, silversmiths, liberation, and the seasons. The female equivalent of Xipe Totec was the goddess Xilonen-Chicomecoatl.

Toci is a deity figuring prominently in the religion and mythology of the pre-Columbian Aztec civilization of Mesoamerica. In Aztec mythology, she is seen as an aspect of the mother goddess Coatlicue or Xochitlicue and is thus labeled “mother of the gods”. She is also called Tlalli Iyollo.

The Aztec religion is a polytheistic and monistic pantheism in which the Nahua concept of teotl was construed as the supreme god Ometeotl, as well as a diverse pantheon of lesser gods and manifestations of nature. The popular religion tended to embrace the mythological and polytheistic aspects, and the Aztec Empire's state religion sponsored both the monism of the upper classes and the popular heterodoxies.

Human sacrifice was common in many parts of Mesoamerica, so the rite was nothing new to the Aztecs when they arrived at the Valley of Mexico, nor was it something unique to pre-Columbian Mexico. Other Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Purépechas and Toltecs, and the Maya performed sacrifices as well and from archaeological evidence, it probably existed since the time of the Olmecs, and perhaps even throughout the early farming cultures of the region. However, the extent of human sacrifice is unknown among several Mesoamerican civilizations. What distinguished Aztec practice from Maya human sacrifice was the way in which it was embedded in everyday life. These cultures also notably sacrificed elements of their own population to the gods.

Toxcatl was the name of the fifth twenty-day month or "veintena" of the Aztec calendar which lasted approximately from the 5th to the 22nd May, and of the festival which was held every year in this month. The Festival of Toxcatl was dedicated to the god Tezcatlipoca and featured the sacrifice of a young man who had been impersonating the deity for a full year.

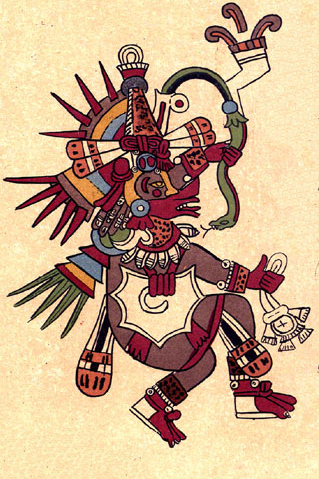

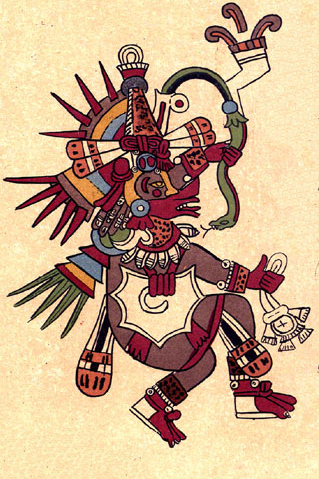

Quetzalcoatl is a deity in Aztec culture and literature. Among the Aztecs, it was related to wind, Venus, Sun, merchants, arts, crafts, knowledge, and learning. It was also the patron god of the Aztec priesthood. It was one of several important gods in the Aztec pantheon, along with the gods Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli. Two other gods represented by the planet Venus are Tlaloc and Xolotl.

Mesoamerican religion is a group of indigenous religions of Mesoamerica that were prevalent in the pre-Columbian era. Two of the most widely known examples of Mesoamerican religion are the Aztec religion and the Mayan religion.

The Double-headed serpent is an Aztec sculpture. It is a snake with two heads composed of mostly turquoise pieces applied to a wooden base. It came from Aztec Mexico and might have been worn or displayed in religious ceremonies. The mosaic is made of pieces of turquoise, spiny oyster shell and conch shell. The sculpture is at the British Museum.

Cē Ācatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl is a mythologised figure appearing in 16th-century accounts of Nahua historical traditions, where he is identified as a ruler in the 10th century of the Toltecs— by Aztec tradition their predecessors who had political control of the Valley of Mexico and surrounding region several centuries before the Aztecs themselves settled there.

In Aztec mythology, Creator-gods are the only four Tezcatlipocas, the children of the creator couple Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl "Lord and Lady of Duality", "Lord and Lady of the Near and the Close", "Father and Mother of the Gods", "Father and Mother of us all", who received the gift of the ability to create other living beings without childbearing. They reside atop a mythical thirteenth heaven Ilhuicatl-Omeyocan "the place of duality".