Asimov's Science Fiction is an American science fiction magazine edited by Sheila Williams and published by Dell Magazines, which is owned by Penny Press. It was launched as a quarterly by Davis Publications in 1977, after obtaining Isaac Asimov's consent for the use of his name. It was originally titled Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, and was quickly successful, reaching a circulation of over 100,000 within a year, and switching to monthly publication within a couple of years. George H. Scithers, the first editor, published many new writers who went on to be successful in the genre. Scithers favored traditional stories without sex or obscenity; along with frequent humorous stories, this gave Asimov's a reputation for printing juvenile fiction, despite its success. Asimov was not part of the editorial team, but wrote editorials for the magazine.

Argosy was an American magazine, founded in 1882 as The Golden Argosy, a children's weekly, edited by Frank Munsey and published by E. G. Rideout. Munsey took over as publisher when Rideout went bankrupt in 1883, and after many struggles made the magazine profitable. He shortened the title to The Argosy in 1888 and targeted an audience of men and boys with adventure stories. In 1894 he switched it to a monthly schedule and in 1896 he eliminated all non-fiction and started using cheap pulp paper, making it the first pulp magazine. Circulation had reached half a million by 1907, and remained strong until the 1930s. The name was changed to Argosy All-Story Weekly in 1920 after the magazine merged with All-Story Weekly, another Munsey pulp, and from 1929 it became just Argosy.

Oriental Stories, later retitled The Magic Carpet Magazine, was an American pulp magazine published by Popular Fiction Co., and edited by Farnsworth Wright. It was launched in 1930 under the title Oriental Stories as a companion to Popular Fiction's Weird Tales, and carried stories with far eastern settings, including some fantasy. Contributors included Robert E. Howard, Frank Owen, and E. Hoffman Price. The magazine was not successful, and in 1932 publication was paused after the Summer issue. It was relaunched in 1933 under the title The Magic Carpet Magazine, with an expanded editorial policy that now included any story set in an exotic location, including other planets.

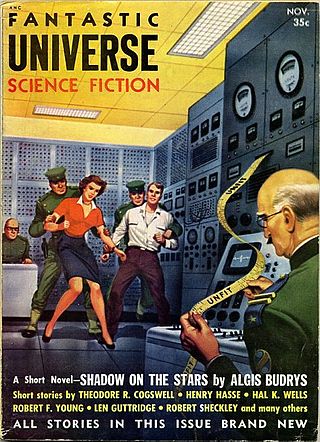

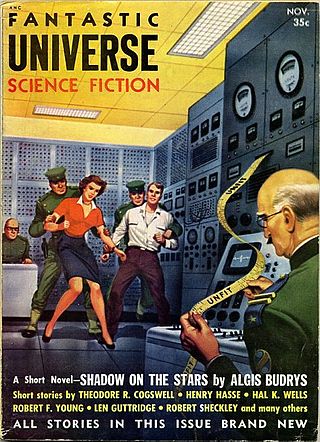

Fantastic Universe was a U.S. science fiction magazine which began publishing in the 1950s. It ran for 69 issues, from June 1953 to March 1960, under two different publishers. It was part of the explosion of science fiction magazine publishing in the 1950s in the United States, and was moderately successful, outlasting almost all of its competitors. The main editors were Leo Margulies (1954–1956) and Hans Stefan Santesson (1956–1960).

Tomorrow Speculative Fiction was a science fiction magazine edited by Algis Budrys, published in print and online in the United States from 1992 to 1999. It was launched by Pulphouse Publishing as part of its attempt to move away from book publishing to magazines, but cash flow problems led Budrys to buy the magazine after the first issue and publish it himself. There were 24 issues as a print magazine from 1993 to 1997, mostly on a bimonthly schedule. The magazine was losing money, and in 1997 Budrys moved to online publishing, rebranding the magazine as tomorrowsf. Readership grew while the magazine was free to read on the web, but plummeted when Budrys began charging for subscriptions. In 1998 Budrys stopped acquiring new fiction, only publishing reprints of his own stories, and in 1999 he shut the magazine down.

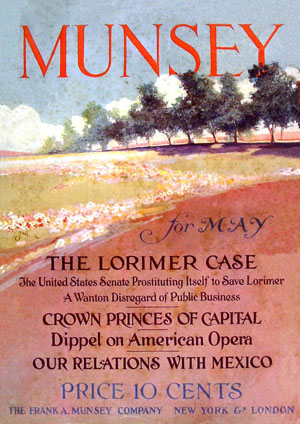

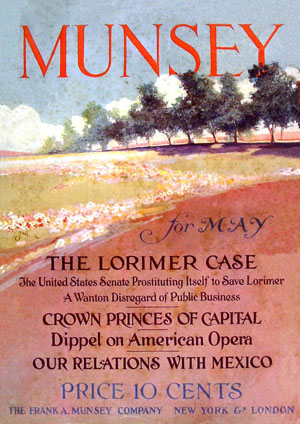

Munsey's Magazine was an American magazine founded by Frank Munsey. Originally launched in 1889 as Munsey's Weekly, a humorous magazine, edited by John Kendrick Bangs, it was not successful, and by late 1891 had lost $100,000. Munsey converted it to a general illustrated monthly in October of that year, retitled Munsey's Magazine and priced at twenty-five cents. Richard Titherington became the editor, and remained in that role for the rest of the magazine's existence. In 1893 Munsey reduced the price to ten cents : this brought him into conflict with the American News Company, which had a near-monopoly on magazine distribution, as they were unwilling to handle the magazine at the cost Munsey asked for. Munsey started his own distribution company and was quickly successful: the first issue at ten cents began with a print run of 20,000 copies but eventually sold 60,000, and within a year circulation had risen to over a quarter of a million issues.

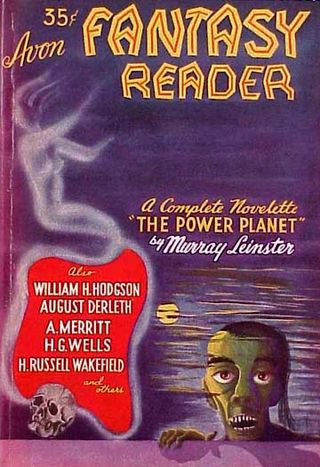

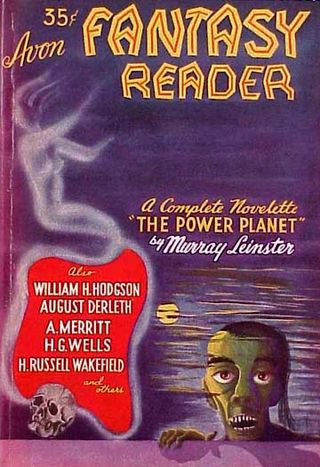

Avon published three related magazines in the late 1940s and early 1950s, titled Avon Fantasy Reader, Avon Science Fiction Reader, and Avon Science Fiction and Fantasy Reader. These were digest size magazines which reprinted science fiction and fantasy literature by now well-known authors. They were edited by Donald A. Wollheim and published by Avon.

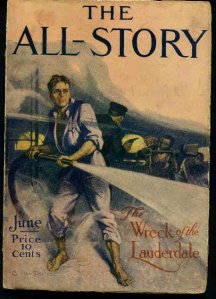

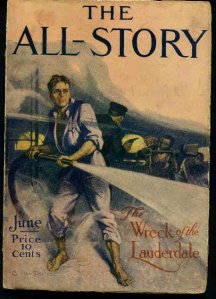

The All-Story Magazine was a Munsey pulp. Debuting in January 1905, this pulp was published monthly until March 1914. Effective March 7, 1914, it changed to a weekly schedule and the title All-Story Weekly. In May 1914, All-Story Weekly was merged with another story pulp, The Cavalier, and used the title All-Story Cavalier Weekly for one year. Editors of All-Story included Newell Metcalf and Robert H. Davis.

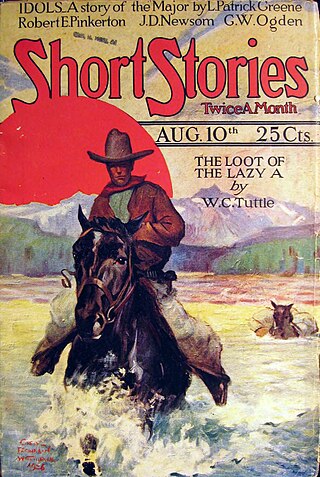

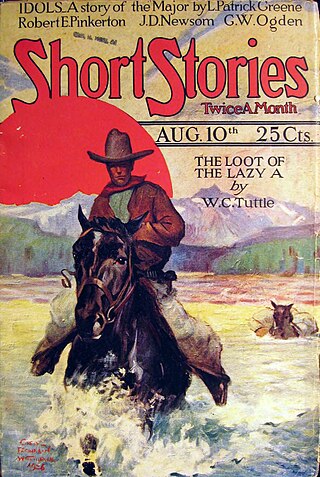

Short Stories was an American fiction magazine published between 1890 and 1959.

Charles Stuart Pratt (1854–1921), who sometimes wrote under the pen names of C. P. Stewart and C. P. Stuart, was an American writer of children's literature, best known for being the art editor of Wide Awake magazine for 16 years, starting in 1875. He edited children’s magazines for 30 years, and for most of that time he worked with his wife, Ella Farman Pratt.

War Birds was a pulp magazine published by Dell from 1928 to 1937. It was the first pulp to focus on stories of war in the air, and soon had competitors. A series featuring fictional Irishman Terence X. O'Leary, which had started in other magazines, began to feature in War Birds in 1933, and in 1935 the magazine changed its name to Terence X. O'Leary's War Birds for three issues. In these issues the setting for stories about O'Leary changed from World War I to the near future; when the title changed back to War Birds later that year, the fiction reverted to ordinary aviation war stories for its last nine issues, including one final O'Leary story. The magazine's editors included Harry Steeger and Carson W. Mowre.

Mind Magic was an American pulp magazine which published six issues in 1931. The publisher was Shade Publishing Company of Philadelphia, and the editor was G.R. Bay. It focused on occult fantasy and non-fiction articles about occult topics. After four issues it changed its title to My Self, perhaps in order to broaden its appeal, but it ceased publication the following issue. Writers who appeared in its pages include Ralph Milne Farley, August Derleth, and Manly Wade Wellman.

The Spider was an American pulp magazine published by Popular Publications from 1933 to 1943. Every issue included a lead novel featuring The Spider, a heroic crime-fighter. The magazine was intended as a rival to Street & Smith's The Shadow and Standard Magazine's The Phantom Detective, which also featured crime-fighting heroes. The novels in the first two issues were written by R. T. M. Scott; thereafter every lead novel was credited to "Grant Stockbridge", a house name. Norvell Page, a prolific pulp author, wrote most of these; almost all the rest were written by Emile Tepperman and A. H. Bittner. The novel in the final issue was written by Prentice Winchell.

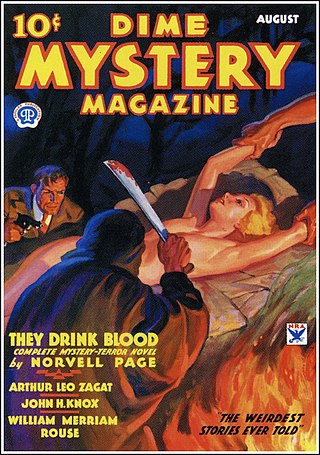

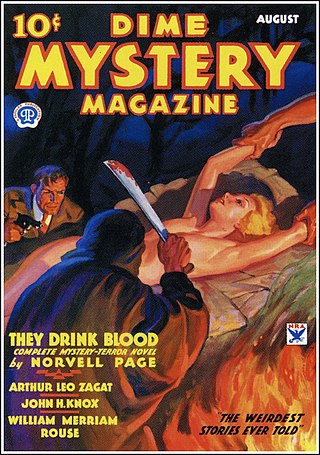

Dime Mystery Magazine was an American pulp magazine published from 1932 to 1950 by Popular Publications. Titled Dime Mystery Book Magazine during its first nine months, it contained ordinary mystery stories, including a full-length novel in each issue, but it was competing with Detective Novels Magazine and Detective Classics, two established magazines from a rival publisher, and failed to sell well. With the October 1933 issue the editorial policy changed, and it began publishing horror stories. Under the new policy, each story's protagonist had to struggle against something that appeared to be supernatural, but would eventually be revealed to have an everyday explanation. The new genre became known as "weird menace" fiction; the publisher, Harry Steeger, was inspired to create the new policy by the gory dramatizations he had seen at the Grand Guignol theater in Paris. Stories based on supernatural events were rare in Dime Mystery, but did occasionally appear.

The Western Raider was an American pulp magazine. The first issue was dated August/September 1938; it was followed by two more issues under that title, publishing Western fiction, and then was changed to a crime fiction pulp for two issues, titled The Octopus and The Scorpion. Both these two issues were named after a supervillain, rather than after a hero who fights crime, as was the case with most such magazines. Norvell Page wrote the lead novels for both the crime fiction issues; the second was rewritten by Ejler Jakobsson, one of the editors, to change the character from The Octopus to The Scorpion.

Captain Zero was an American pulp magazine that published three issues in 1949 and 1950. The lead novels, written by G.T. Fleming-Roberts, featured Lee Allyn, who had been the subject of an experiment with radiation, and as a result was invisible between midnight and dawn. Under the name Captain Zero, Allyn became a vigilante, fighting crime at night. Allyn had no other superpowers, and the novels were straightforward mysteries in Weinberg's opinion, though pulp historian Robert Sampson considers them to be "complex...[they] pound along with hair-raising incidents..full of twists and high suspense". Captain Zero was the last crime-fighter hero magazine to be launched in the pulp era, ending an era that had begun with The Shadow in 1931. There was room in the magazine for only one or two short stories along with the lead novel; these were all straight mystery stories, without the veneer of science fiction of the Captain Zero novels.

Battle Birds was an American air-war pulp magazine, published by Popular Publications. It was launched at the end of 1932, but did not sell well, and in 1934 the publisher turned it into an air-war hero pulp titled Dusty Ayres and His Battle Birds. Robert Sidney Bowen, an established pulp writer, provided the lead novel each month, and also wrote the short stories that filled out the issue. Bowen's stories were set in the future, with the United States menaced by an Asian empire called the Black Invaders. The change was not successful enough to be extended beyond the initial plan of a year, and Bowen wrote a novel in which, unusually for pulp fiction, Dusty Ayres finally defeated the invaders, to end the series. The magazine ceased publication with the July/August 1935 issue. It restarted in 1940, under the original title, Battle Birds, and lasted for another four years. All the cover art was painted by Frederick Blakeslee.

Marvel Tales and Unusual Stories were two related American semi-professional science fiction magazines published in 1934 and 1935 by William L. Crawford. Crawford was a science fiction fan who believed that the pulp magazines of the time were too limited in what they would publish. In 1933, he distributed a flyer announcing Unusual Stories, and declaring that no taboos would prevent him from publishing worthwhile fiction. The flyer included a page from P. Schuyler Miller's "The Titan", which Miller had been unable to sell to the professional magazines because of its sexual content. A partial issue of Unusual Stories was distributed in early 1934, but Crawford then launched a new title, Marvel Tales, in May 1934. A total of five issues of Marvel Tales and three of Unusual Stories appeared over the next two years.

Nelly Littlehale Umbstaetter Murphy (1867–1941) was an American artist. She was born in Stockton, California, and moved to Boston when she married her first husband, Herman Umbstaetter. She drew many of the covers for The Black Cat, the magazine her husband edited from 1895 to 1912, and a collection of the covers was advertised as a free gift with subscriptions to the magazine in 1905. She studied with Joseph De Camp and Charles Howard Walker. Her first husband died in 1913, and she married Hermann Dudley Murphy in 1916.

Herman Daniel Umbstaetter was an American businessman and founder of the magazine The Black Cat.