Egoism is a philosophy concerned with the role of the self, or ego, as the motivation and goal of one's own action. Different theories of egoism encompass a range of disparate ideas and can generally be categorized into descriptive or normative forms. That is, they may be interested in either describing that people do act in self-interest or prescribing that they should. Other definitions of egoism may instead emphasise action according to one's will rather than one's self-interest, and furthermore posit that this is a truer sense of egoism.

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems. Although usually contrasted to social anarchism, both individualist and social anarchism have influenced each other. Some anarcho-capitalists claim anarcho-capitalism is part of the individualist anarchist tradition, while others disagree and claim individualist anarchism is only part of the socialist movement and part of the libertarian socialist tradition. Mutualism, an economic theory sometimes considered a synthesis of communism and property, has been considered individualist anarchism and other times part of social anarchism. Many anarcho-communists regard themselves as radical individualists, seeing anarcho-communism as the best social system for the realization of individual freedom. Economically, while European individualist anarchists are pluralists who advocate anarchism without adjectives and synthesis anarchism, ranging from anarcho-communist to mutualist economic types, most American individualist anarchists of the 19th century advocated mutualism, a libertarian socialist form of market socialism, or a free-market socialist form of classical economics. Individualist anarchists are opposed to property that violates the entitlement theory of justice, that is, gives privilege due to unjust acquisition or exchange, and thus is exploitative, seeking to "destroy the tyranny of capital, — that is, of property" by mutual credit.

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and advocating that the interests of the individual should gain precedence over the state or a social group, while opposing external interference upon one's own interests by society or institutions such as the government. Individualism makes the individual its focus, and so starts "with the fundamental premise that the human individual is of primary importance in the struggle for liberation".

Johann Kaspar Schmidt, known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen as one of the forerunners of nihilism, existentialism, psychoanalytic theory, postmodernism and individualist anarchism.

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful as well as opposing authority and hierarchical organization in the conduct of human relations. Proponents of anarchism, known as anarchists, advocate stateless societies based on non-hierarchical voluntary associations. While anarchism holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, opposition to the state is not its central or sole definition. Anarchism can entail opposing authority or hierarchy in the conduct of all human relations.

Individualist anarchism in the United States was strongly influenced by Benjamin Tucker, Josiah Warren, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Lysander Spooner, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Max Stirner, Herbert Spencer and Henry David Thoreau. Other important individualist anarchists in the United States were Stephen Pearl Andrews, William Batchelder Greene, Ezra Heywood, M. E. Lazarus, John Beverley Robinson, James L. Walker, Joseph Labadie, Steven Byington and Laurance Labadie.

James L. Walker, sometimes known by the pen name Tak Kak, was an American individualist anarchist of the Egoist school, born in Manchester, United Kingdom.

Sidney Parker, also known as S. E. Parker, was an English egoist and a former individualist anarchist who wrote articles and edited several journals from 1963–1993. Notably Parker wrote the introductions to the books Might is Right and The Ego and Its Own by Max Stirner.

Philosophical anarchism is an anarchist school of thought which focuses on intellectual criticism of authority, especially political power, and the legitimacy of governments. The American anarchist and socialist Benjamin Tucker coined the term philosophical anarchism to distinguish peaceful evolutionary anarchism from revolutionary variants. Although philosophical anarchism does not necessarily imply any action or desire for the elimination of authority, philosophical anarchists do not believe that they have an obligation or duty to obey any authority or conversely that the state or any individual has a right to command. Philosophical anarchism is a component especially of individualist anarchism.

Egoist anarchism or anarcho-egoism, often shortened as simply egoism, is a school of anarchist thought that originated in the philosophy of Max Stirner, a 19th-century philosopher whose "name appears with familiar regularity in historically orientated surveys of anarchist thought as one of the earliest and best known exponents of individualist anarchism".

Individualist anarchism in Europe proceeded from the roots laid by William Godwin and soon expanded and diversified through Europe, incorporating influences from individualist anarchism in the United States. Individualist anarchism is a tradition of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasize the individual and his or her will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems. While most American individualist anarchists advocate mutualism, a libertarian socialist form of market socialism, or a free-market socialist form of classical economics, European individualist anarchists are pluralists who advocate anarchism without adjectives and synthesis anarchism, ranging from anarcho-communist to mutualist economic types.

The relation between anarchism and Friedrich Nietzsche has been ambiguous. Even though Nietzsche criticized anarchists, his thought proved influential for many of them. As such "[t]here were many things that drew anarchists to Nietzsche: his hatred of the state; his disgust for the mindless social behavior of 'herds'; his anti-Christianity; his distrust of the effect of both the market and the State on cultural production; his desire for an 'übermensch'—that is, for a new human who was to be neither master nor slave".

This is a list of articles in modern philosophy.

Max Stirner's idea of the "Union of egoists" was first expounded in The Ego and Its Own. A union of egoists is understood as a voluntary and non-systematic association which Stirner proposed in contradistinction to the state. Each union is understood as a relation between egoists which is continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will. The Union requires that all parties participate out of a conscious egoism. If one party silently finds themselves to be suffering, but puts up and keeps the appearance, the union has degenerated into something else. This union is not seen as an authority above a person's own will, but a voluntary relation subordinate to the wills of its members. This idea has received interpretations for politics, economics, romance and sexual relations.

Some observers believe that existentialism forms a philosophical ground for anarchism. Anarchist historian Peter Marshall claims "there is a close link between the existentialists' stress on the individual, free choice, and moral responsibility and the main tenets of anarchism".

German individualist philosopher Max Stirner became an important early influence in anarchism. Afterwards Johann Most became an important anarchist propagandist in both Germany and in the United States. In the late 19th century and early 20th century there appeared individualist anarchists influenced by Stirner such as John Henry Mackay, Adolf Brand and Anselm Ruest and Mynona.

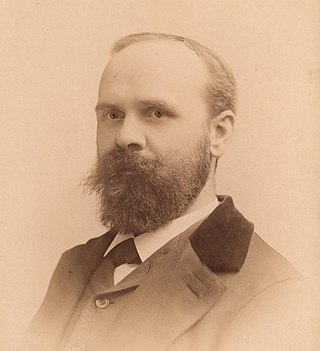

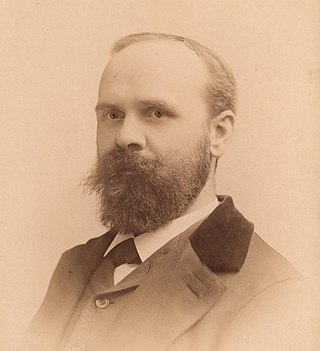

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker was an American individualist anarchist. Tucker was the editor and publisher of the American individualist anarchist periodical Liberty (1881–1908). Tucker was a member of the First International, with his publication Liberty represented as the English language organ for the Socialistic-Revolutionary Congress. Tucker described his form of anarchism as "consistent Manchesterism" and stated that "the Anarchists are simply unterrified Jeffersonian Democrats."

The German Ideology, also known as A Critique of the German Ideology, is a set of manuscripts written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels around April or early May 1846. Marx and Engels did not find a publisher, but the work was retrieved and first published in 1932 by the Soviet Union's Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute. The book uses satirical polemics to critique modern German philosophy, particularly that of young Hegelians such as Marx's former mentor Bruno Bauer, Ludwig Feuerbach, and Max Stirner's The Ego and Its Own. It criticizes "ideology" as a form of "historical idealism", as opposed to Marx's historical materialism. The first part of Volume I also examines the division of labor and Marx's theory of human nature, on which he states that humans "distinguish themselves from animals as soon as they begin to produce their means of subsistence".

The Young Hegelians, or Left Hegelians (Linkshegelianer), or the Hegelian Left, were a group of German intellectuals who, in the decade or so after the death of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in 1831, reacted to and wrote about his ambiguous legacy. The Young Hegelians drew on his idea that the purpose and promise of history was the total negation of everything conducive to restricting freedom and reason; and they proceeded to mount radical critiques, first of religion and then of the Prussian political system. They rejected anti-utopian aspects of his thought that "Old Hegelians" have interpreted to mean that the world has already essentially reached perfection.

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew from various sources, and the official philosophy in the Soviet Union, which enforced a rigid reading of Marx called dialectical materialism, in particular during the 1930s. Marxist philosophy is not a strictly defined sub-field of philosophy, because the diverse influence of Marxist theory has extended into fields as varied as aesthetics, ethics, ontology, epistemology, social philosophy, political philosophy, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of history. The key characteristics of Marxism in philosophy are its materialism and its commitment to political practice as the end goal of all thought. The theory is also about the struggles of the proletariat and their reprimand of the bourgeoisie.