Related Research Articles

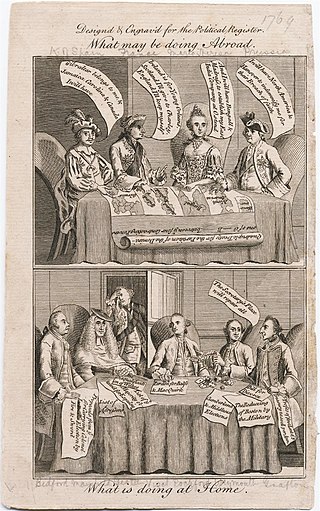

John Wilkes was an English radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he fought for the right of his voters—rather than the House of Commons—to determine their representatives. In 1768, angry protests of his supporters were suppressed in the Massacre of St George's Fields. In 1771, he was instrumental in obliging the government to concede the right of printers to publish verbatim accounts of parliamentary debates. In 1776, he introduced the first bill for parliamentary reform in the British Parliament.

George Grenville was a British Whig statesman who rose to the position of Prime Minister of Great Britain. Grenville was born into an influential political family and first entered Parliament in 1741 as an MP for Buckingham. He emerged as one of Cobham's Cubs, a group of young members of Parliament associated with Lord Cobham.

Richard Grenville-Temple, 2nd Earl Temple,, was a British politician. He is best known for his association with his brother-in-law William Pitt with whom he served in government during Britain's participation in the Seven Years War between 1756 and 1761. He resigned, along with Pitt, in protest at the cabinet's failure to declare war on Spain.

Winchester Palace was a 12th-century palace which served as the London townhouse of the Bishops of Winchester. It was located in the parish of Southwark in Surrey, on the south bank of the River Thames on what is now Clink Street in the London Borough of Southwark, near St Saviour's Church which later became Southwark Cathedral. Grade II listed remains of the demolished palace survive on the site today, designated a Scheduled Ancient Monument, under the care of English Heritage.

George Montagu-Dunk, 2nd Earl of Halifax, was a British statesman of the Georgian era. Due to his success in extending commerce in the Americas, he became known as the "father of the colonies". President of the Board of Trade from 1748 to 1761, he aided the foundation of Nova Scotia, 1749, the capital Halifax being named after him. When Canada was ceded to the King of Great Britain by the King of France, following the Treaty of Paris of 1763, he restricted its boundaries and renamed it "Province of Quebec".

Charles Churchill was an English poet and satirist.

Herne is a village in South East England, divided by the Thanet Way from the seaside resort of Herne Bay. Administratively it is in the civil parish of Herne and Broomfield in Kent. Between Herne and Broomfield is the former hamlet of Hunters Forstal. Herne Common lies to the south on the A291 road.

The 1768 British general election returned members to serve in the House of Commons of the 13th Parliament of Great Britain to be held, after the merger of the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland in 1707.

The King's Bench Prison was a prison in Southwark, south London, England, from medieval times until it closed in 1880. It took its name from the King's Bench court of law in which cases of defamation, bankruptcy and other misdemeanours were heard; as such, the prison was often used as a debtor's prison until the practice was abolished in the 1860s. In 1842, it was renamed the Queen's Bench Prison, and became the Southwark Convict Prison in 1872.

Events from the year 1690 in England.

John Glynn Serjeant-at-law of Glynn (1722–1779) was an English lawyer and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1768 to 1779. Glynn was born to a family of Cornish gentry. He inherited his father's estate at Glynn in the parish of Cardinham, Cornwall, on the deaths of his elder brother and his nephew.

Stephen Sayre (1736–1818) was a member of a thousand-strong American community living in London at the time of the outbreak of the War of Independence in 1775. A close associate of John Wilkes, the radical Lord Mayor of London, Sayre, a merchant and a city sheriff, is alleged to have planned to kidnap George III with the help of the London mob. The King was to be taken to the Tower of London, before being bundled off to his ancient patrimony in Hanover.

St James Duke's Place was an Anglican parish church in the Aldgate ward of the City of London It was established in the early 17th century, rebuilt in 1727 and closed and demolished in 1874.

Philip Carteret Webb was an English barrister, involved with the 18th-century antiquarian movement.

The Massacre of St George's Fields occurred on 10 May 1768 when government soldiers opened fire on demonstrators that had gathered at St George's Fields, Southwark, in south London. The protest was against the imprisonment of the radical Member of Parliament John Wilkes for writing an article that severely criticised King George III. After the reading of the Riot Act telling the crowds to disperse within the hour, six or seven people were killed when fired on by troops. The incident in Britain entrenched the enduring idiom of "reading the Riot Act to someone", meaning "to reprimand severely", with the added sense of a stern warning. The phrase remains in common use in the English language.

John Sawbridge was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1768 to 1780.

William Tyler was an English sculptor, landscaper, and architect, and one of the three founding members of the Royal Academy, in 1768. He was Director of the Society of Artists.

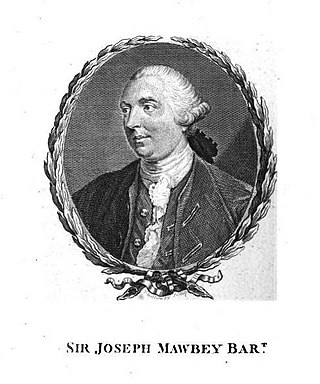

Sir Joseph Mawbey, 1st Baronet (1730–1798) was an English distiller and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1761 and 1790. He was a supporter of John Wilkes.

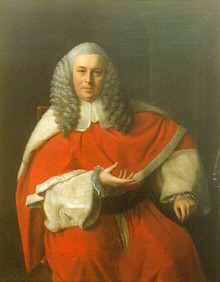

Sir George Nares (1716–1786) was an English barrister, judge, and politician.

References

- ↑ Noorthouck, John (1773). A New History of London: Including Westminster and Southwark. pp. 419–450.

- ↑ Cash, Arthur (2006). John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty . New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-300-12363-9.

- ↑ Dew, Benjamin. ""waving a mouchoir a la ' wilkes": hume, radicalism and the north briton∗" (PDF). the core. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ↑ Tilly, C. (2004). Social Movements, 1768–2004 . Paradigm. ISBN 1-59451-043-1.

- ↑ Nichols, John (1812). Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century. London: Nichols, Son, and Bentley. pp. 631–632.

- ↑ Noorthouck, John (1773). A New History of London: Including Westminster and Southwark. pp. 450–485.