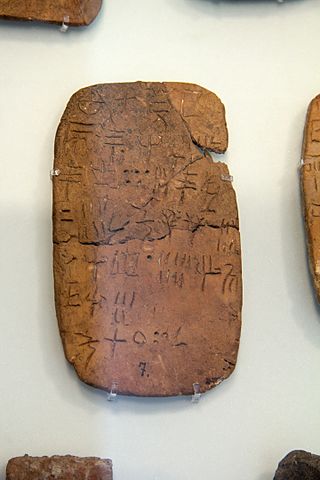

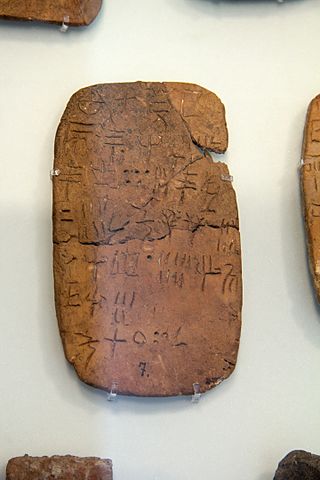

Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 BC to 1450 BC. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civilization. It was succeeded by Linear B, which was used by the Mycenaeans to write an early form of Greek. It was discovered by the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in 1900. No texts in Linear A have yet been deciphered. Evans named the script "Linear" because its characters consisted simply of lines inscribed in clay, in contrast to the more pictographic characters in Cretan hieroglyphs that were used during the same period.

Linear B is a syllabic script that was used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of the Greek language. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries, the earliest known examples dating to around 1400 BC. It is adapted from the earlier Linear A, an undeciphered script potentially used for writing the Minoan language, as is the later Cypriot syllabary, which also recorded Greek. Linear B, found mainly in the palace archives at Knossos, Kydonia, Pylos, Thebes and Mycenae, disappeared with the fall of Mycenaean civilization during the Late Bronze Age collapse. The succeeding period, known as the Greek Dark Ages, provides no evidence of the use of writing.

Michael George Francis Ventris, was an English architect, classicist and philologist who deciphered Linear B, the ancient Mycenaean Greek script. A student of languages, Ventris had pursued decipherment as a personal vocation since his adolescence. After creating a new field of study, Ventris died in a car crash a few weeks before the publication of Documents in Mycenaean Greek, written with John Chadwick.

The Phaistos Disc or Phaistos Disk is a disk of fired clay from the island of Crete, Greece, possibly from the middle or late Minoan Bronze Age, bearing a text in an unknown script and language. Its purpose and its original place of manufacture remain disputed. It is now on display at the archaeological museum of Heraklion. The name is sometimes spelled Phaestos or Festos.

A palace economy or redistribution economy is a system of economic organization in which a substantial share of the wealth flows into the control of a centralized administration, the palace, and out from there to the general population. In turn the population may be allowed its own sources of income but relies heavily on the wealth distributed by the palace. It was traditionally justified on the principle that the palace was most capable of distributing wealth efficiently for the benefit of society. The temple economy is a similar concept.

Mycenaean Greek is the most ancient attested form of the Greek language, on the Greek mainland and Crete in Mycenaean Greece, before the hypothesised Dorian invasion, often cited as the terminus ad quem for the introduction of the Greek language to Greece. The language is preserved in inscriptions in Linear B, a script first attested on Crete before the 14th century BC. Most inscriptions are on clay tablets found in Knossos, in central Crete, as well as in Pylos, in the southwest of the Peloponnese. Other tablets have been found at Mycenae itself, Tiryns and Thebes and at Chania, in Western Crete. The language is named after Mycenae, one of the major centres of Mycenaean Greece.

John Chadwick, was an English linguist and classical scholar who was most notable for the decipherment, with Michael Ventris, of Linear B.

The Minoan language is the language of the ancient Minoan civilization of Crete written in the Cretan hieroglyphs and later in the Linear A syllabary. As the Cretan hieroglyphs are undeciphered and Linear A only partly deciphered, the Minoan language is unknown and unclassified; with the existing evidence, it is impossible to be certain that the two scripts record the same language.

Potnia is an Ancient Greek word for "Mistress, Lady" and a title of a goddess. The word was inherited by Classical Greek from Mycenean Greek with the same meaning and it was applied to several goddesses. A similar word is the title Despoina, "the mistress", which was given to the nameless chthonic goddess of the mysteries of Arcadian cult. She was later conflated with Kore (Persephone), "the maiden", the goddess of the Eleusinian Mysteries, in a life-death rebirth cycle which leads the neophyte from death into life and immortality. Karl Kerenyi identifies Kore with the nameless "Mistress of the labyrinth", who probably presided over the palace of Knossos in Minoan Crete.

Amnisos, also Amnissos and Amnisus, is the current but unattested name given to a Bronze Age settlement on the north shore of Crete that was used as a port to the palace city of Knossos. It appears in Greek literature and mythology from the earliest times, but its origin is far earlier, in prehistory. The historic settlement belonged to a civilization now called Minoan. Excavations at Amnissos in 1932 uncovered a villa that included the "House of the Lilies", which was named for the lily theme that was depicted in a wall fresco.

Alice Elizabeth Kober was an American classicist best known for her work on the decipherment of Linear B. Educated at Hunter College and Columbia University, Kober taught classics at Brooklyn College from 1930 until her death. In the 1940s, she published three major papers on the script, demonstrating evidence of inflection; her discovery allowed for the deduction of phonetic relationships between different signs without assigning them phonetic values, and would be a key step in the eventual decipherment of the script.

The Cypro-Minoan syllabary (CM), more commonly called the Cypro-Minoan Script, is an undeciphered syllabary used on the island of Cyprus and at its trading partners during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age. The term "Cypro-Minoan" was coined by Arthur Evans in 1909 based on its visual similarity to Linear A on Minoan Crete, from which CM is thought to be derived. Approximately 250 objects—such as clay balls, cylinders, and tablets which bear Cypro-Minoan inscriptions, have been found. Discoveries have been made at various sites around Cyprus, as well as in the ancient city of Ugarit on the Syrian coast. It is thought to be somehow related to the later Cypriot syllabary.

Linear Elamite was a writing system used in Elam during the Bronze Age between c. 2300 and 1850 BCE, and known mainly from a few extant monumental inscriptions. It was used contemporaneously with Elamite cuneiform and records the Elamite language. The French archaeologist François Desset and his colleagues have argued that it is the oldest known purely phonographic writing system, although others, such as the linguist Michael Mäder, have argued that it is partly logographic.

The American Journal of Archaeology (AJA), the peer-reviewed journal of the Archaeological Institute of America, has been published since 1897. The publication was co-founded in 1885 by Princeton University professors Arthur Frothingham and Allan Marquand. Frothingham became the first editor, serving until 1896.

Mycenaean pottery is the pottery tradition associated with the Mycenaean period in Ancient Greece. It encompassed a variety of styles and forms including the stirrup jar. The term "Mycenaean" comes from the site Mycenae, and was first applied by Heinrich Schliemann.

The William Saroyan International Prize for Writing is a biennial literary award for fiction and nonfiction in the spirit of William Saroyan by emerging writers. It was established by Stanford University Libraries and the William Saroyan Foundation to "encourage new or emerging writers rather than recognize established literary figures;" the prize being $12,500.

Margalit Fox is an American writer. After earning a master's degree in linguistics, she began her career in publishing in the 1980s. In 1994, she joined The New York Times as a copy editor for its Book Review and later wrote widely on language, culture and ideas for The New York Times, New York Newsday, Variety and other publications. She joined the obituary department of The New York Times in 2004 and authored over 1,400 obituaries before her retirement from the staff of the paper in 2018. Fox has written several nonfiction books.

Emmett Leslie Bennett Jr. was an American classicist and philologist whose systematic catalog of its symbols led to the solution of reading Linear B, a 3,300-year-old syllabary used for writing Mycenaean Greek hundreds of years before the Greek alphabet was developed. Archaeologist Arthur Evans had discovered Linear B in 1900 during his excavations at Knossos on the Greek island of Crete and spent decades trying to comprehend its writings until his death in 1941. Bennett and Alice Kober cataloged the 80 symbols used in the script in his 1951 work The Pylos Tablets, which provided linguist John Chadwick and amateur scholar Michael Ventris with the vital clues needed to finally decipher Linear B in 1952.

Mycenology is the study of the Mycenaean Greek language and the culture and institutions recorded in that language. It emerged as a discipline auxiliary to classical philology in 1953, following the deciphering of Minoan Linear B script by Alice Kober, Michael Ventris and John Chadwick.

PY Ta 641, sometimes known as the Tripod Tablet, is a Mycenaean clay tablet inscribed in Linear B, currently displayed in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Discovered in the so-called "Archives Complex" of the Palace of Nestor at Pylos in Messenia in June 1952 by the American archaeologist Carl Blegen, it has been described as "probably the most famous tablet of Linear B".