Thomas Stearns Eliot was a poet, essayist, publisher, playwright, literary critic and editor. Considered one of the 20th century's major poets, he is a central figure in English-language Modernist poetry. Through his trials in language, writing style, and verse structure, he reinvigorated English poetry. He also dismantled outdated beliefs and established new ones through a collection of critical essays.

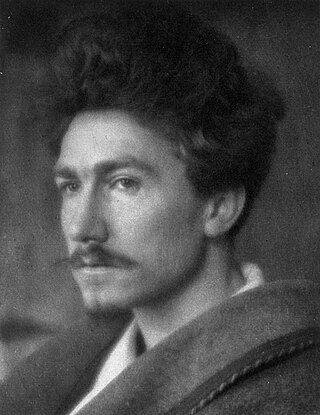

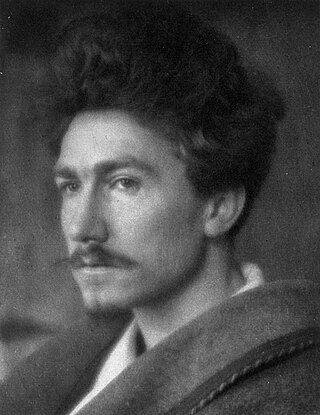

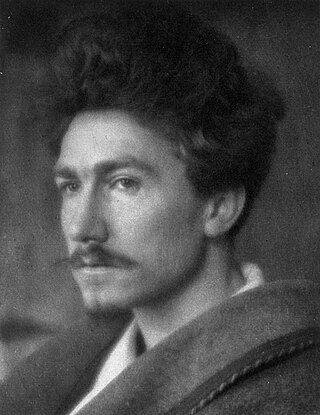

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a collaborator in Fascist Italy and the Salò Republic during World War II. His works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), and his 800-page epic poem, The Cantos.

Richard Aldington was an English writer and poet. He was an early associate of the Imagist movement. His 50-year writing career covered poetry, novels, criticism and biography. He edited The Egoist, a literary journal, and wrote for The Times Literary Supplement, Vogue, The Criterion, and Poetry. His biography of Wellington (1946) won him the James Tait Black Memorial Prize.

Ford Madox Ford was an English novelist, poet, critic and editor whose journals The English Review and The Transatlantic Review were important in the development of early 20th-century English and American literature.

William Carlos Williams was an American poet, writer, and physician closely associated with modernism and imagism.

Imagism was a movement in early-20th-century Anglo-American poetry that favored precision of imagery and clear, sharp language. It is considered to be the first organized modernist literary movement in the English language. Imagism is sometimes viewed as "a succession of creative moments" rather than a continuous or sustained period of development. The French academic René Taupin remarked that "it is more accurate to consider Imagism not as a doctrine, nor even as a poetic school, but as the association of a few poets who were for a certain time in agreement on a small number of important principles".

Hilda Doolittle was an American modernist poet, novelist, and memoirist who wrote under the name H.D. throughout her life. Her career began in 1911 after she moved to London and co-founded the avant-garde Imagist group of poets with American expatriate poet and critic Ezra Pound. During this early period, her minimalist free verse poems depicting Classical motifs drew international attention. Eventually distancing herself from the Imagist movement, she experimented with a wider variety of forms, including fiction, memoir, and verse drama. Reflecting the trauma she experienced in London during the Blitz, H.D.'s poetic style from World War II until her death pivoted towards complex long poems on esoteric and pacifist themes.

"The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock", commonly known as "Prufrock", is the first professionally published poem by American-born British poet T. S. Eliot (1888–1965). The poem relates the varying thoughts of its title character in a kind of stream of consciousness. Eliot began writing "Prufrock" in February 1910, and it was first published in the June 1915 issue of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse at the instigation of Ezra Pound (1885–1972). It was later printed as part of a twelve-poem pamphlet titled Prufrock and Other Observations in 1917. At the time of its publication, Prufrock was considered outlandish, but is now seen as heralding a paradigmatic cultural shift from late 19th-century Romantic verse and Georgian lyrics to Modernism.

William Hugh Kenner was a Canadian literary scholar, critic and professor. He published widely on Modernist literature with particular emphasis on James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and Samuel Beckett. His major study of the period, The Pound Era, argued for Pound as the central figure of Modernism, and is considered one of the most important works on the topic.

Thomas Ernest Hulme was an English critic and poet who, through his writings on art, literature and politics, had a notable influence upon modernism. He was an aesthetic philosopher and the 'father of imagism'.

The Egoist was a London literary magazine published from 1914 to 1919, during which time it published important early modernist poetry and fiction. In its manifesto, it claimed to "recognise no taboos", and published a number of controversial works, such as parts of Ulysses. Today, it is considered "England's most important Modernist periodical."

Lu Ji (261–303), courtesy name Shiheng, was a Chinese essayist, military general, politician, and writer who lived during the late Three Kingdoms period and Jin dynasty of China. He was the fourth son of Lu Kang, a general of the state of Eastern Wu in the Three Kingdoms period, and a grandson of Lu Xun, a prominent general and statesman who served as the third Imperial Chancellor of Eastern Wu.

Literary modernism, or modernist literature, originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and is characterized by a self-conscious break with traditional ways of writing in both poetry and prose fiction writing. Modernism experimented with literary form and expression, as exemplified by Ezra Pound's maxim to "Make it new." This literary movement was driven by a conscious desire to overturn traditional modes of representation and express the new sensibilities of the time. The horrors of the First World War saw the prevailing assumptions about society reassessed, and much modernist writing engages with the technological advances and societal changes of modernity moving into the 20th century. In Modernist Literature, Mary Ann Gillies notes that these literary themes share the "centrality of a conscious break with the past", one that "emerges as a complex response across continents and disciplines to a changing world".

Richard Sieburth is Professor Emeritus of French Literature, Thought and Culture and Comparative Literature at New York University (NYU). A translator and editor, Sieburth retired in 2019 after 35 years of teaching at NYU and 10 years at Harvard.

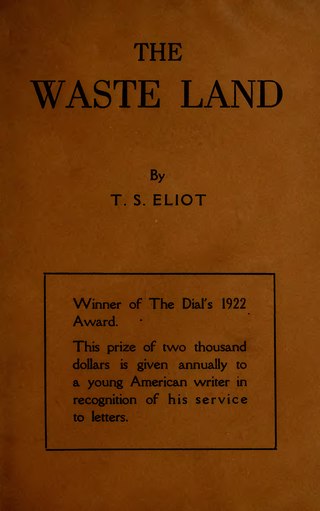

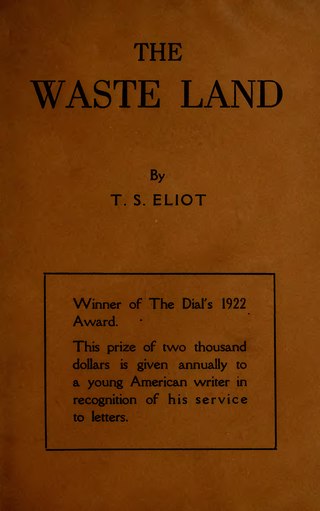

The Waste Land is a poem by T. S. Eliot, widely regarded as one of the most important poems of the 20th century and a central work of modernist poetry. Published in 1922, the 434-line poem first appeared in the United Kingdom in the October issue of Eliot's The Criterion and in the United States in the November issue of The Dial. It was published in book form in December 1922. Among its famous phrases are "April is the cruelest month", "I will show you fear in a handful of dust", "These fragments I have shored against my ruins" and the Sanskrit mantra "Datta, Dayadhvam, Damyata" and "Shantih shantih shantih".

Stephen Romer, FRSL is an English poet, academic and literary critic.

Peter Ackroyd is an English biographer, novelist and critic with a specialist interest in the history and culture of London. For his novels about English history and culture and his biographies of, among others, William Blake, Charles Dickens, T. S. Eliot, Charlie Chaplin and Sir Thomas More, he won the Somerset Maugham Award and two Whitbread Awards. He is noted for the volume of work he has produced, the range of styles therein, his skill at assuming different voices, and the depth of his research.

The Taylorian Lecture, sometimes referred to as the "Special Taylorian Lecture" or "Taylorian Special Lecture", is a prestigious annual lecture on Modern European Literature, delivered at the Taylor Institution in the University of Oxford since 1889.

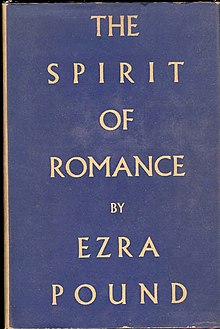

A Lume Spento is a 1908 poetry collection by Ezra Pound. Self-published in Venice, it was his first collection.

John Gery is an American poet, critic, collaborative translator, and editor. He has published seven books of poetry, a critical work on the treatment of nuclear annihilation in American poetry, two co-edited volumes of literary criticism and two co-edited anthologies of contemporary poetry, as well as, a co-authored biography and guidebook on Ezra Pound's Venice.