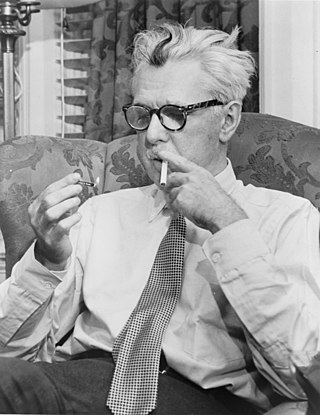

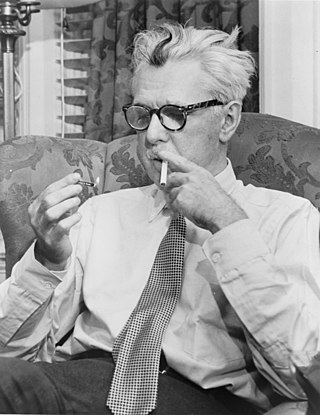

James Grover Thurber was an American cartoonist, writer, humorist, journalist and playwright. He was best known for his cartoons and short stories, published mainly in The New Yorker and collected in his numerous books.

Gerald McBoing-Boing is an animated short film about a little boy who speaks through sound effects instead of spoken words. It was produced by United Productions of America (UPA) and given wide release by Columbia Pictures on November 2, 1950. It was adapted by Phil Eastman and Bill Scott from a story by Dr. Seuss, directed by Robert Cannon, and produced by John Hubley.

My World ... and Welcome to It is an American half-hour television sitcom based on the humor and cartoons of James Thurber.

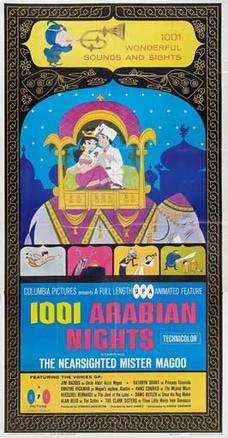

United Productions of America, better known as UPA, was an American animation studio and later distribution company founded in 1941 as Industrial Film and Poster Service by former Walt Disney Productions employees. Beginning with industrial and World War II training films, UPA eventually produced theatrical shorts for Columbia Pictures such as the Mr. Magoo series. In 1956, UPA produced a television series for CBS, The Boing-Boing Show, hosted by Gerald McBoing Boing. In the 1960s, UPA produced syndicated Mr. Magoo and Dick Tracy television series and other series and specials, including Mister Magoo's Christmas Carol. UPA also produced two animated features, 1001 Arabian Nights and Gay Purr-ee, and distributed Japanese films from Toho Studios in the 1970s and 1980s.

The golden age of American animation was a period in the history of U.S. animation that began with the popularization of sound cartoons in 1928 and gradually ended from 1957 to 1969, where theatrical animated shorts began losing popularity to the newer medium of television animation since in 1957, produced on cheaper budgets and in a more limited animation style by companies such as Terrytoons, UPA, Paramount Cartoon Studios, Jay Ward Productions, Hanna-Barbera, DePatie-Freleng, Rankin/Bass and Filmation. In artefact, the history of animation became very important in the United States.

David Raksin was an American composer who was noted for his work in film and television. With more than 100 film scores and 300 television scores to his credit, he became known as the "Grandfather of Film Music.". Though to give Raksin this title is debatable remembering the very talented composers who worked during the Golden Age of Hollywood including Max Steiner, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and others.

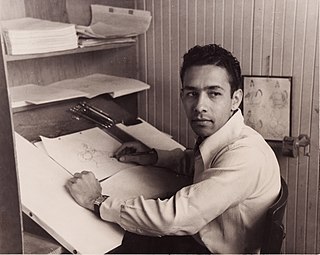

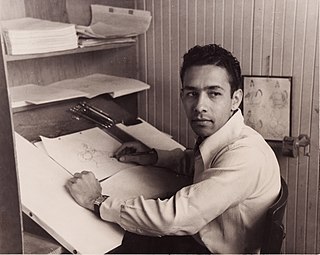

John Kirkham Hubley was an American animated film director, art director, producer, and writer known for his work with the United Productions of America (UPA) and his own independent studio, Storyboard, Inc.. A pioneer and innovator in the American animation industry, Hubley pushed for more visually and emotionally complex films than those being produced by contemporaries like the Walt Disney Company and Warner Brothers Animation. He and his second wife, Faith Hubley, who he worked alongside from 1953 onward, were nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning three.

Rudolph Larriva was an American animator and director from the 1940s to the 1980s.

ASIFA-Hollywood, an American non-profit organization in Los Angeles, California, is a branch member of the International Animated Film Association. Its purpose is to promote the art of film animation in a variety of ways, including its own archive and an annual awards presentation, the Annie Awards. It is also known as the International Animated Film Society.

Jules Engel was an American filmmaker, painter, sculptor, graphic artist, set designer, animator, film director, and teacher of Hungarian origin. He was the founding director of the experimental animation program at the California Institute of the Arts, where he taught until his death, serving as mentor to several generations of animators.

Stephen Reginald Bosustow was a Canadian-born American film producer from 1943 until his retirement in 1979. He was one of the founders of United Productions of America (UPA) and produced nearly 600 cartoon and live-action shorts. He is chiefly remembered for producing a string of Mr. Magoo and Gerald McBoing-Boing cartoons in the 1950s, three of which earned Academy Awards. He is the only film producer in history who received all the Oscar nominations in one category (1956), guaranteeing him the winning Oscar. Magoo's Puddle Jumper was the eventual winner.

"The Unicorn in the Garden" is a short story written by James Thurber. One of the most famous of Thurber's humorous modern fables, it first appeared in The New Yorker on October 21, 1939; and was first collected in his book Fables for Our Time and Famous Poems Illustrated. The fable has since been reprinted in The Thurber Carnival, James Thurber: Writings and Drawings, The Oxford Book of Modern Fairy Tales, and other publications. It is taught in literature and rhetoric courses.

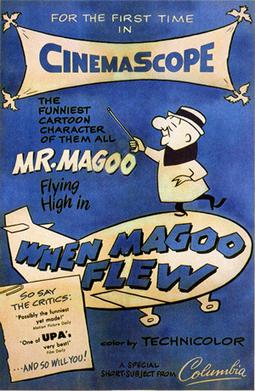

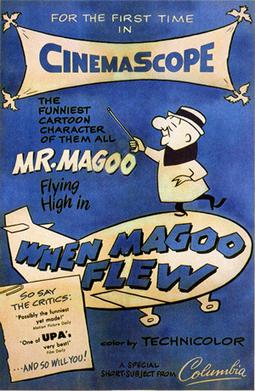

When Magoo Flew is a 1954 animated short produced by UPA for Columbia Pictures. Directed by Pete Burness and produced by Stephen Bosustow, When Magoo Flew won the 1955 Oscar for Short Subjects (Cartoons). In addition, it was the first UPA short to be made for the CinemaScope widescreen format. When Magoo Flew is also the title of a 2012 book by Adam Abraham on the history of the UPA studio.

David Hilberman was an American animator and one of the founders of classic 1940s animation. An innovator in the animation industry, he co-founded United Productions of America (UPA). The studio gave its artists great freedom and pioneered the modern style of animation. As Animator and Professor Tom Sito noted: "Arguably, no studio since Walt Disney exerted such a great influence on world animation." He and Zack Schwartz went on to start Tempo Productions which became an early leader in television animated commercial production. In short, he played an important role in the new directions the art form took in the 1940s and '50s.

Man Alive! is a 1952 American animated short documentary film directed by William T. Hurtz.

Henry Gahagen Saperstein was an American film producer and distributor.

Wilson D. "Pete" Burness was an American animator and animation director. He was perhaps best known for his work on the Mr. Magoo series. He also contributed to the Tom and Jerry series, Looney Tunes, Merrie Melodies, and Rocky and His Friends.

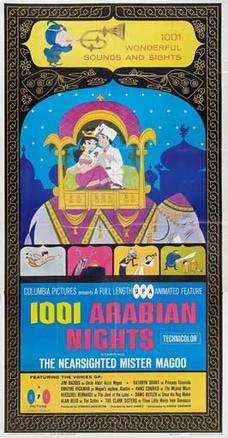

1001 Arabian Nights is a 1959 American animated comedy film produced by United Productions of America (UPA) and distributed by Columbia Pictures. Released to theaters on December 1, 1959, the film is a loose adaptation of the Arab folktale of "Aladdin" from One Thousand and One Nights, albeit with the addition of UPA's star cartoon character, Mr. Magoo, to the story as Aladdin's uncle, "Abdul Azziz Magoo". It is the first animated feature to be released by Columbia Pictures.

Events in 1911 in animation.

Sterling Sturtevant (1922–1962) was a designer and art director for animated cartoons in an era in which few women were worked in Hollywood animation. Some of her early work was done under her married name Sterling Glasband.