Related Research Articles

The history of feminism comprises the narratives of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending on time, culture, and country, most Western feminist historians assert that all movements that work to obtain women's rights should be considered feminist movements, even when they did not apply the term to themselves. Some other historians limit the term "feminist" to the modern feminist movement and its progeny, and use the label "protofeminist" to describe earlier movements.

Sex-positive feminism, also known as pro-sex feminism, sex-radical feminism, or sexually liberal feminism, is a feminist movement centering on the idea that sexual freedom is an essential component of women's freedom. They oppose legal or social efforts to control sexual activities between consenting adults, whether they are initiated by the government, other feminists, opponents of feminism, or any other institution. They embrace sexual minority groups, endorsing the value of coalition-building with marginalized groups. Sex-positive feminism is connected with the sex-positive movement. Sex-positive feminism brings together anti-censorship activists, LGBT activists, feminist scholars, producers of pornography and erotica, among others. Sex-positive feminists believe that prostitution can be a positive experience if workers are treated with respect, and agree that sex work should not be criminalized.

Sisterhood Is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women's Liberation Movement is a 1970 anthology of feminist writings edited by Robin Morgan, a feminist poet and founding member of New York Radical Women. It is one of the first widely available anthologies of second-wave feminism. It is both a consciousness-raising analysis and a call-to-action. Sisterhood Is Global: The International Women's Movement Anthology (1984) is the follow-up to Sisterhood Is Powerful. After Sisterhood Is Global came its follow-up, Sisterhood Is Forever: The Women's Anthology for a New Millennium (2003).

The Female Eunuch is a 1970 book by Germaine Greer that became an international bestseller and an important text in the feminist movement. Greer's thesis is that the "traditional" suburban, consumerist, nuclear family represses women sexually, and that this devitalises them, rendering them eunuchs. The book was published in London in October 1970. It received a mixed reception, but by March 1971, it had nearly sold out its second printing. It has been translated into eleven languages.

Sexual Politics is the debut book by American writer and activist Kate Millett, based on her PhD dissertation at Columbia University. It was published in 1970 by Doubleday. It is regarded as a classic of feminism and one of radical feminism's key texts, a formative piece in shaping the intentions of the second-wave feminist movement. In Sexual Politics, an explicit focus is placed on male dominance throughout prominent 20th century art and literature. According to Millett, western literature reflects patriarchal constructions and the heteronormativity of society. She argues that men have established power over women, but that this power is the result of social constructs rather than innate or biological qualities.

Feminist literature is fiction, nonfiction, drama, or poetry, which supports the feminist goals of defining, establishing, and defending equal civil, political, economic, and social rights for women. It often identifies women's roles as unequal to those of men – particularly as regarding status, privilege, and power – and generally portrays the consequences to women, men, families, communities, and societies as undesirable.

Germaine Greer is an Australian writer and public intellectual, regarded as one of the major voices of the second-wave feminism movement in the latter half of the 20th century.

Atheist feminism is a branch of feminism that also advocates atheism. Atheist feminists hold that religion is a prominent source of female oppression and inequality, believing that the majority of the religions are sexist and oppressive towards women.

Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature (TSWL), founded by Germaine Greer in 1982, is devoted to the study of women's literature and women's writing in general. Publishing "articles, notes, research, and reviews of literary, historicist, and theoretical work by established and emerging scholars in the field of women's literature and feminist theory", it has been described as the "longest-running academic journal focusing exclusively on women's writing".

Womyn-born womyn (WBW) is a term developed during second-wave feminism to designate women who were assigned female at birth, were raised as girls, and identify as women. The policy is noted for exclusion of trans women. Third-wave feminism and fourth-wave feminism have generally done away with the idea of WBW.

Kira Cochrane is a British journalist and novelist. She is the Head of Features at The Guardian, and worked previously as Head of Opinion. Cochrane is an advocate for women's rights, as well as an active participant in fourth wave feminist movements.

Feminist views on transgender topics vary widely.

Helen Alexandra Lewis is a British journalist and a staff writer at The Atlantic. She is a former deputy editor of the New Statesman, and has also written for The Guardian and The Sunday Times.

The Everyday Sexism Project is a website founded on 16 April 2012 by Laura Bates, a British feminist writer. The aim of the site is to document examples of sexism from around the world. Entries may be submitted directly to the site, or by email or tweet. The accounts of abuse are collated by a small group of volunteers.

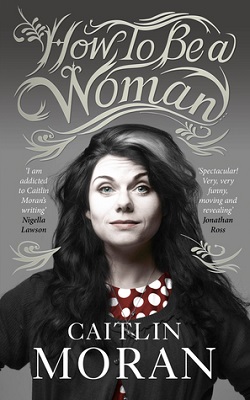

How to Be a Woman is a 2011 non-fiction memoir by British writer Caitlin Moran. The book documents Moran's early life including her views on feminism. As of July 2014, it had sold over a million copies.

Gender inequality is any situation in which people are not treated equally on the basis of gender. In the United Kingdom, the genders are unequally impacted by economic policies, face different levels of media attention, and face inequality in education and employment, which includes a persistent national gender pay gap. Furthermore, according to numerous sources, there exists a pervasive lad culture which has decreased the ability of women to participate in different parts of society.

Australia has a long-standing association with the protection and creation of women's rights. Australia was the second country in the world to give women the right to vote and the first to give women the right to be elected to a national parliament. The Australian state of South Australia, then a British colony, was the first parliament in the world to grant women full suffrage rights. Australia has since had multiple notable women serving in public office as well as other fields. Women in Australia with the notable exception of Indigenous women, were granted the right to vote and to be elected at federal elections in 1902.

Fourth-wave feminism is a feminist movement that began around 2012 and is characterized by a focus on the empowerment of women, the use of internet tools, and intersectionality. The fourth wave seeks greater gender equality by focusing on gendered norms and the marginalization of women in society.

Multiracial feminist theory is promoted by women of color (WOC), including Black, Latina, Asian, Native American, and anti-racist white women. In 1996, Maxine Baca Zinn and Bonnie Thornton Dill wrote “Theorizing Difference from Multiracial Feminism," a piece emphasizing intersectionality and the application of intersectional analysis within feminist discourse.

Town Bloody Hall is a 1979 documentary film of a panel debate between feminist advocates and activist Norman Mailer. Filmed on April 30, 1971, in The Town Hall in New York City. Town Bloody Hall features a panel of feminist advocates for the women's liberation movement and Norman Mailer, author of The Prisoner of Sex (1971). Chris Hegedus and D. A. Pennebaker produced the film, which stars Jacqueline Ceballos, Germaine Greer, Jill Johnston, Diana Trilling, and Norman Mailer. The footage of the panel was recorded and released as a documentary in 1979. Produced by Shirley Broughton, the event was originally filmed by Pennebaker. The footage was then filed and rendered unusable. Hegedus met Pennebaker a few years later, and the two edited the final version of the film for its release in 1979. Pennebaker described his filming style as one that exists without labels, in order to let the viewer come to a conclusion about the material, which inspired the nature of the Town Bloody Hall documentary. The recording of the debate was intended to ensure the unbiased documentation, allowing it to become a concrete moment in feminist history.

References

- ↑ de Mello, Lianne (23 October 2012). "Caitlin Moran and Lena Dunham are great, but take note Vagenda - feminism isn't just a white middle class movement" . The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022.

- 1 2 Gribbin, Alice (14 May 2012). "The Vagenda joins NewStatesman.com". www.newstatesman.com.

- ↑ Lewis, Helen (1 March 2012). "Police corruption, the duck house of Hackgate and King Lear for girls". www.newstatesman.com.

- 1 2 3 "What's on the Vagenda?". Evening Standard. 22 February 2012.

- 1 2 Griffiths, Elen (25 March 2012). "What's on the Vagenda?". The Sunday Times. ISSN 0956-1382.

- ↑ Dalston Darlings event, 1 February 2013

- ↑ Murray-Browne, Kate (5 November 2012). "Working motherhood: not sure a band of cupcake 'mumpreneurs' is the answer". The Guardian.

- ↑ Cosslett, Rhiannon Lucy (26 October 2012). "Dressing up for Halloween: a feminist's guide". The Guardian.

- ↑ Rhiannon and Holly (18 February 2013). "The Vagenda List of the Quietly Awesome". www.newstatesman.com.

- ↑ Woman's Hour, BBC Radio 4, 28 February 2012

- ↑ New Statesman "Women's magazines: exposing their vagenda" 14 May 2012

- ↑ Williams, Charlotte (17 September 2012). "Square Peg signs The Vagenda in six-figure deal". www.thebookseller.com.

- ↑ "Best holiday reads 2014 - top authors recommend their favourites". The Guardian. 12 July 2014.

- ↑ Greer, Germaine (14 May 2014). "The failures of the new feminism". www.newstatesman.com.

- ↑ Baxter, Holly (19 December 2013). "Why celebrity crowdfunding has little appeal". The Guardian.

- ↑ Cooke, Rachel (14 April 2014). "Everyday Sexism and The Vagenda review – everything you wanted to know about sexism, except how to fight it". The Guardian.

- ↑ Williams, Zoe (24 April 2014). "Everyday Sexism and The Vagenda – review". The Guardian.

- ↑ "On Bikini Body Bullshit | The Vagenda". vagendamagazine.com. 24 June 2014.

- ↑ Rhiannon and Holly (28 April 2014). "The Vagenda: why we must fight back against media that is sexist and degrading to women". www.newstatesman.com.

- ↑ "10 Things that Having a Feminist Book Out Teaches You | The Vagenda". vagendamagazine.com. 10 March 2015.

- ↑ Rumbelow, Helen (24 April 2014). "The Vagenda guide to feminism". The Times.