This article needs additional citations for verification .(July 2007) |

This article needs additional citations for verification .(July 2007) |

Morgan was first a dissenter preacher, then a practicer of healing among the Quakers, and finally a writer.

He was the author of a large three-volume work entitled The Moral Philosopher. It is a dialogue between a Christian Jew, Theophanes, and a Christian deist, Philalethes. [2] According to Orr, this book did not add many new ideas to the deistic movement, but did vigorously restate and give new illustrations to some of its main ideas. [1] The first volume of The Moral Philosopher appeared anonymously in the year 1737. It was the most important of the three volumes, the other two being mostly replies to critics of the first volume. John Leland, John Chapman and others answered the first volume of Morgan's book, and it was these answers that prompted Morgan to write the second and third volumes.

His particular antipathy was to Judaism and the Old Testament, although he by no means accepted the New Testament. He favored Gnosticism, and called himself a "Christian deist". He asserted that the conflict between the Apostle Paul and Peter in Galatians shows that Paul was a true follower of Jesus whereas Peter and James were not following Jesus' teachings à la Paul. [3]

The positive aspect of Morgan's teachings included all of the articles of natural religion formulated by Lord Herbert of Cherbury. The negative part of Morgan's work was much more extensive than the positive, and included an attack on the Bible, especially the Old Testament.

Recently the scholar Joseph Waligore has shown in his article "The Piety of the English Deists" [4] that Thomas Morgan believed in divine guidance and offered instruction on how to prepare oneself to receive it. To receive divine inspiration, he counseled, one must rein in his personal desires and abandon all concern for wealth, power, ambition, or physical gratifications. Abandoning worldly desires, one might then enter into what he called "silent Solitude." After a person did this, he can be divinely inspired. "When a man does this, he converses with God, he derives Communication of Light and Knowledge from the eternal Father and Fountain of it; he receives Intelligence and Information from eternal Wisdom, and hears the clear intelligible Voice of his Maker and Former speaking to his silent, undisturb'd attentive Reason." [5] However, right after the statements just quoted, the dialogue's orthodox Christian interlocutor then said that this position was religious enthusiasm: "I see there is a sort of enthusiasm, which you not only allow, but naturally run into, and cannot help it." [6] Morgan did not deny this charge of enthusiasm.

Waligore also has shown that Thomas Morgan wrote an extremely pious prayer which emphasized his dependence on God and called on God to continually lead him. He said:

O thou eternal Reason, Father of Light, and immense Fountain of all Truth and Goodness; suffer me, with the deepest Humility and Awe to apply to and petition thee. . . . I own, therefore, O Father of Spirits, this natural, necessary Dependence upon thy constant, universal Presence, Power and Agency. Take me under the constant, uninterrupted Protection and Care of thy Divine Wisdom, Benignity and All-sufficiency: Continue to irradiate my Understanding with Beams of immutable, eternal Reason. Let this infallible Light from Heaven inform and teach me. . . . if I should err from the Way of Truth, and wander in the Dark, instruct me by a fatherly Correction; let Pains and Sorrows fetch me home, and teach me Wisdom; . . . for ever bless me with the enlightening, felicitating Influence of thy benign Presence, Power and Love. [7]

Thomas Morgan is a good example of a deist that believed in immutable laws, but one that also believed in particular providences or miracles. In one of his later works, Morgan said God does not break the general laws he has made by doing miracles:

God governs the World, and directs all Affairs, not by particular and occasional, but by general, uniform and established Laws; and the Reason why he does not miraculously interpose, as they would have him, by suspending or setting aside the general, established Laws of Nature and Providence, is, because this would subvert the whole Order of the Universe, and destroy all the Wisdom and Contrivance of the first Plan. [8]

It seems Morgan's insistence on immutable laws leaves no room for miracles. Nevertheless, in the same book, he said he believed in miracles; it is just these miracles were done by angels in accordance with the general, established laws of nature.

Morgan sought to explain angelic miracles by a comparison to animal husbandry. He said that humans care for animals and control their lives without breaking general laws, and from the animals' point of view our work must seem miraculous or "all particular Interposition, and supernatural Agency." [9] In the same way, Morgan asserted, the angels can do what seem like miracles to us without breaking the uniform laws of nature. He said that if we could see the "other intelligent free Agents above us, who have the same natural establish'd Authority and Command over us, as we have with regard to the inferior Ranks and Classes of Creatures, the Business of Providence, moral Government, and particular Interpositions by general Laws of Nature would be plain enough." [10]

Morgan's writings are:

Deism is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation of the natural world are exclusively logical, reliable, and sufficient to determine the existence of a Supreme Being as the creator of the universe. More simply stated, Deism is the belief in the existence of God, solely based on rational thought without any reliance on revealed religions or religious authority. Deism emphasizes the concept of natural theology—that is, God's existence is revealed through nature.

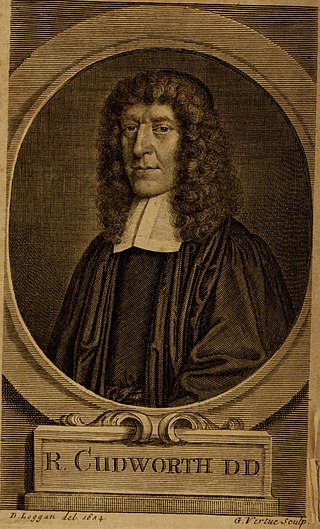

Ralph Cudworth was an English Anglican clergyman, Christian Hebraist, classicist, theologian and philosopher, and a leading figure among the Cambridge Platonists who became 11th Regius Professor of Hebrew (1645–88), 26th Master of Clare Hall (1645–54), and 14th Master of Christ's College (1654–88). A leading opponent of Hobbes's political and philosophical views, his magnum opus was his The True Intellectual System of the Universe (1678).

John Balguy was an English divine and philosopher.

Joseph Butler was an English Anglican bishop, theologian, apologist, and philosopher, born in Wantage in the English county of Berkshire. He is known for critiques of Deism, Thomas Hobbes's egoism, and John Locke's theory of personal identity. The many philosophers and religious thinkers Butler influenced included David Hume, Thomas Reid, Adam Smith, Henry Sidgwick, John Henry Newman, and C. D. Broad, and is widely seen as "one of the pre-eminent English moralists." He played a major, if underestimated role in developing 18th-century economic discourse, influencing the Dean of Gloucester and political economist Josiah Tucker.

Edward Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Cherbury KB was an English soldier, diplomat, historian, poet and religious philosopher of the Kingdom of England.

Matthew Tindal was an eminent English deist author. His works, highly influential at the dawn of the Enlightenment, caused great controversy and challenged the Christian consensus of his time.

The Boyle Lectures are named after Robert Boyle, a prominent natural philosopher of the 17th century and son of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork. Under the terms of his Will, Robert Boyle endowed a series of lectures or sermons which were to consider the relationship between Christianity and the new natural philosophy then emerging in European society.

The existence of God is a subject of debate in theology, philosophy of religion and popular culture. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God or deities can be categorized as logical, empirical, metaphysical, subjective or scientific. In philosophical terms, the question of the existence of God or deities involves the disciplines of epistemology and ontology and the theory of value.

The Cambridge Platonists were an influential group of Platonist philosophers and Christian theologians at the University of Cambridge that existed during the 17th century. The leading figures were Ralph Cudworth and Henry More.

Samuel Chandler was an English Nonconformist minister and pamphleteer. He has been called the "uncrowned patriarch of Dissent" in the latter part of George II's reign.

Thomas Chubb was a lay English Deist writer born near Salisbury. He saw Christ as a divine teacher, but held reason to be sovereign over religion. He questioned the morality of religions, while defending Christianity on rational grounds. Despite little schooling, Chubb was well up on the religious controversies. His The True Gospel of Jesus Christ, Asserted sets out to distinguish the teaching of Jesus from that of the Evangelists. Chubb's views on free will and determinism, expressed in A Collection of Tracts on Various Subjects (1730), were extensively criticised by Jonathan Edwards in Freedom of the Will (1754).

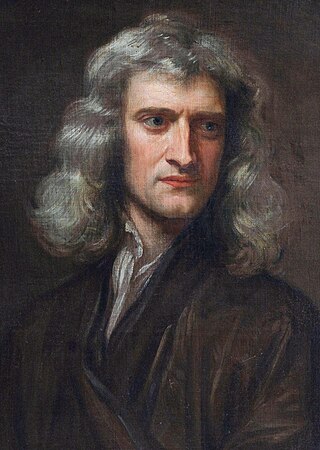

Isaac Newton was considered an insightful and erudite theologian by his Protestant contemporaries. He wrote many works that would now be classified as occult studies, and he wrote religious tracts that dealt with the literal interpretation of the Bible. He kept his heretical beliefs private.

The religious views of Thomas Jefferson diverged widely from the traditional Christianity of his era. Throughout his life, Jefferson was intensely interested in theology, religious studies, and morality. Jefferson was most comfortable with Deism, rational religion, theistic rationalism, and Unitarianism. He was sympathetic to and in general agreement with the moral precepts of Christianity. He considered the teachings of Jesus as having "the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man," yet he held that the pure teachings of Jesus appeared to have been appropriated by some of Jesus' early followers, resulting in a Bible that contained both "diamonds" of wisdom and the "dung" of ancient political agendas.

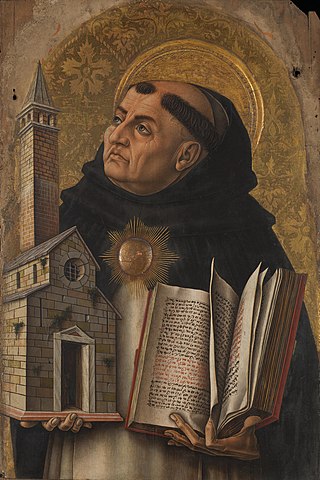

Thomas Aquinas was an Italian Dominican friar and priest, an influential philosopher and theologian, and a jurist in the tradition of scholasticism from the county of Aquino in the Kingdom of Sicily, Italy.

Christian deism is a standpoint in the philosophy of religion stemming from Christianity and Deism. It refers to Deists who believe in the moral teachings—but not the divinity—of Jesus. Corbett and Corbett (1999) cite John Adams and Thomas Jefferson as exemplars.

Deism, the religious attitude typical of the Enlightenment, especially in France and England, holds that the only way the existence of God can be proven is to combine the application of reason with observation of the world. A Deist is defined as "One who believes in the existence of a God or Supreme Being but denies revealed religion, basing his belief on the light of nature and reason." Deism was often synonymous with so-called natural religion because its principles are drawn from nature and human reasoning. In contrast to Deism there are many cultural religions or revealed religions, such as Judaism, Trinitarian Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and others, which believe in supernatural intervention of God in the world; while Deism denies any supernatural intervention and emphasizes that the world is operated by natural laws of the Supreme Being.

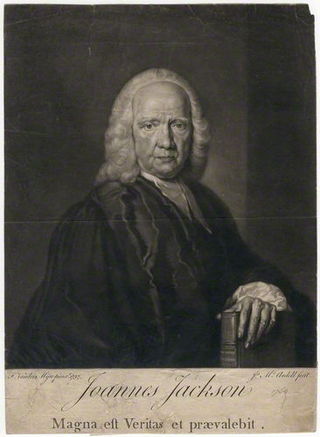

John Jackson (1686–1763) was an English clergyman and controversial theological writer.

John Hildrop was an English cleric, known as a religious writer and essayist. Hildrop authored one of the earliest works on animal rights.

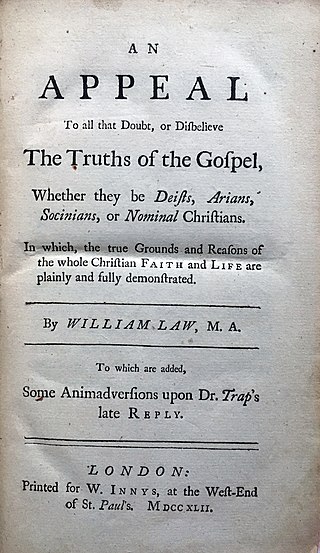

An Appeal to all that Doubt or Disbelieve the Truths of the Gospel, whether they be Deists, Arians, Socinians, or nominal Christians, or An Appeal for short, was written by William Law in 1742. Law lived in the Age of Enlightenment centering on reason in which there were controversies between Catholics and Protestants, Deists, Socinians, Arians etc. which caused conflicts that worried him. The Appeal was heavily influenced by the works of the seventeenth-century German philosopher, Lutheran theologian and mystic writer Jakob Boehme.