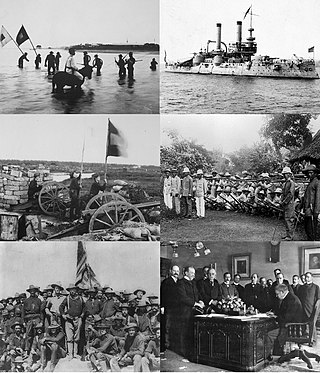

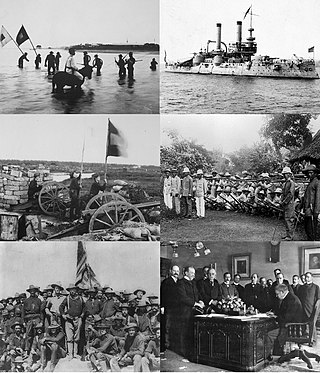

The Spanish–American War began in the aftermath of the internal explosion of USS Maine in Havana Harbor in Cuba, leading to United States intervention in the Cuban War of Independence. The war led to the United States emerging predominant in the Caribbean region, and resulted in U.S. acquisition of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. It also led to United States involvement in the Philippine Revolution and later to the Philippine–American War.

The Treaty of Peace between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain, commonly known as the Treaty of Paris of 1898, was signed by Spain and the United States on December 10, 1898, that ended the Spanish–American War. Under it, Spain relinquished all claim of sovereignty over and title to territories described there as the island of Porto Rico and other islands now under Spanish sovereignty in the West Indies, and the island of Guam in the Marianas or Ladrones, the archipelago known as the Philippine Islands, and comprehending the islands lying within the following line:, to the United States. The cession of the Philippines involved a compensation of $20 million from the United States to Spain.

The Battle of Santiago de Cuba was a decisive naval engagement that occurred on July 3, 1898 between an American fleet, led by William T. Sampson and Winfield Scott Schley, against a Spanish fleet led by Pascual Cervera y Topete, which occurred during the Spanish–American War. The significantly more powerful US Navy squadron, consisting of four battleships and two armored cruisers, decisively defeated an outgunned squadron of the Royal Spanish Navy, consisting of four armored cruisers and two destroyers. All of the Spanish ships were sunk for no American loss. The crushing defeat sealed the American victory in the Cuban theater of the war, ensuring the independence of Cuba from Spanish rule.

The Puerto Rico campaign was the American military sea and land operation on the island of Puerto Rico during the Spanish–American War. The offensive began on May 12, 1898, when the United States Navy attacked the capital, San Juan. Though the damage inflicted on the city was minimal, the Americans were able to establish a blockade in the city's harbor, San Juan Bay. On June 22, the cruiser Isabel II and the destroyer Terror delivered a Spanish counterattack, but were unable to break the blockade and Terror was damaged.

The Battle of Manila, sometimes called the Mock Battle of Manila, was a land engagement which took place in Manila on August 13, 1898, at the end of the Spanish–American War, four months after the decisive victory by Commodore Dewey's Asiatic Squadron at the Battle of Manila Bay. The belligerents were Spanish forces led by Governor-General of the Philippines Fermín Jáudenes, and American forces led by United States Army Major General Wesley Merritt and United States Navy Commodore George Dewey. American forces were supported by units of the Philippine Revolutionary Army, led by Emilio Aguinaldo.

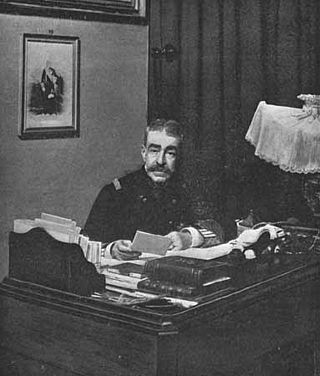

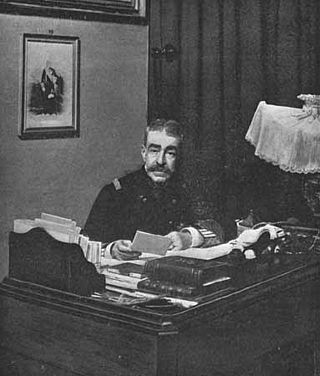

Admiral Segismundo Bermejo y Merelo was a Spanish naval officer who served as chief of staff in the Spanish Navy and Minister of the Navy during the Spanish–American War. He was most notable for his role in dispatching Rear Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete, in command of a squadron of four cruisers and three destroyers, to Cuba in May 1898. It set up the conditions for the naval Battle of Santiago de Cuba. Bermejo himself was forced to resign as naval minister after the defeat of the Spanish Pacific Squadron at the Battle of Manila Bay by the U.S. Navy, and he died a year later.

The Cuban War of Independence, also known in Cuba as The Necessary War, fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Little War (1879–1880). The final three months of the conflict escalated to become the Spanish–American War, with United States forces being deployed in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippine Islands against Spain. Historians disagree as to the extent that United States officials were motivated to intervene for humanitarian reasons but agree that yellow journalism exaggerated atrocities attributed to Spanish forces against Cuban civilians.

The Battle of the Aguadores was a sharp skirmish on the banks of the Aguadores River near Santiago de Cuba, on 1 July 1898, at the height of the Spanish–American War. The American attack was intended as a feint to draw Spanish defenders away from their nearby positions at San Juan Hill and El Caney, where the main blows fell later that day.

The history of the Philippines from 1898 to 1946 is known as the American colonial period, and began with the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in April 1898, when the Philippines was still a colony of the Spanish East Indies, and concluded when the United States formally recognized the independence of the Republic of the Philippines on July 4, 1946.

The presidency of William McKinley began on March 4, 1897, when William McKinley was inaugurated and ended September 14, 1901, upon his assassination. A longtime Republican, McKinley is best known for conducting the successful Spanish–American War (1898), freeing Cuba from Spain; taking ownership of the Republic of Hawaii; and purchasing the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico. It includes the 1897 Dingley Tariff which raised rates to protect manufacturers and factory workers from foreign competition, and the Gold Standard Act of 1900 that rejected free silver inflationary proposals. Rapid economic growth and a decline in labor conflict marked the presidency and he was easily reelected.

The Flying Squadron was a United States Navy force that operated in the Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico and the Spanish West Indies during the first half of the Spanish–American War. The squadron included many of America's most modern warships which engaged the Spanish in a blockade of Cuba.

The Third Battle of Manzanillo was a naval engagement that occurred on July 18, 1898, between an American fleet commanded by Chapman C. Todd against a Spanish fleet led by Joaquín Gómez de Barreda, which occurred during the Spanish–American War. The significantly more powerful United States Navy squadron, consisting of four gunboats, two armed tugs and a patrol yacht, overpowered a Royal Spanish Navy squadron which consisted of four gunboats, three pontoon used as floating batteries and three transports, sinking or destroying all the Spanish ships present without losing a single ship of their own. The victory came on the heels of a more significant American success at the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, and was the third largest naval engagement of the war after Santiago de Cuba and the Battle of Manila Bay.

Events from the year 1898 in the United States.

The Round-Robin Letter is the name of an incident in the United States Army that occurred between July 28 and August 3, 1898, during the Spanish–American War. After disease incapacitated thousands of Army soldiers in the wake of the Siege of Santiago, high-ranking officers of Fifth Army Corps drafted a round-robin letter demanding that the unit be sent back to the United States. Public release of the letter embarrassed the U.S. government.

José Toral y Velázquez was a Spanish Army general who was a divisional commander of IV Corps in Cuba during the Spanish–American War. He surrendered the city of Santiago de Cuba on July 17, 1898, after the Siege of Santiago.

The United States Military Government of the Philippine Islands was a military government in the Philippines established by the United States on August 14, 1898, a day after the capture of Manila, with General Wesley Merritt acting as military governor. During military rule (1898–1902), the U.S. military commander governed the Philippines under the authority of the U.S. president as Commander-in-Chief of the United States Armed Forces. After the appointment of a civil Governor-General, the procedure developed that as parts of the country were pacified and placed firmly under American control, responsibility for the area would be passed to the civilian.

Francis John Higginson was an officer in the United States Navy during the American Civil War and Spanish–American War. He rose to the rank of rear admiral and was the last commander-in-chief of the North Atlantic Squadron and first commander-in-chief of the North Atlantic Fleet.

The presidency of William McKinley began on March 4, 1897, when William McKinley was inaugurated the 25th president of the United States, and it ended with McKinley's death on September 14, 1901.

The Battle of San Roque was fought during the Philippine-American War between the United States and the First Philippine Republic. The battle resulted in the Filipinos being pushed off the causeway near San Roque, and forcing them to abandon their planned attack upon Cavite City itself.