In mathematics, differential topology is the field dealing with the topological properties and smooth properties of smooth manifolds. In this sense differential topology is distinct from the closely related field of differential geometry, which concerns the geometric properties of smooth manifolds, including notions of size, distance, and rigid shape. By comparison differential topology is concerned with coarser properties, such as the number of holes in a manifold, its homotopy type, or the structure of its diffeomorphism group. Because many of these coarser properties may be captured algebraically, differential topology has strong links to algebraic topology.

Differential geometry is a mathematical discipline that studies the geometry of smooth shapes and smooth spaces, otherwise known as smooth manifolds, using the techniques of differential calculus, integral calculus, linear algebra and multilinear algebra. The field has its origins in the study of spherical geometry as far back as antiquity, as it relates to astronomy and the geodesy of the Earth, and later in the study of hyperbolic geometry by Lobachevsky. The simplest examples of smooth spaces are the plane and space curves and surfaces in the three-dimensional Euclidean space, and the study of these shapes formed the basis for development of modern differential geometry during the 18th century and the 19th century.

In mathematics, curvature is any of several strongly related concepts in geometry. Intuitively, the curvature is the amount by which a curve deviates from being a straight line, or a surface deviates from being a plane.

In mathematics, the winding number or winding index of a closed curve in the plane around a given point is an integer representing the total number of times that curve travels counterclockwise around the point, i.e., the curve's number of turns. The winding number depends on the orientation of the curve, and it is negative if the curve travels around the point clockwise.

The Gauss–Bonnet theorem, or Gauss–Bonnet formula, is a relationship between surfaces in differential geometry. It connects the curvature of a surface to its Euler characteristic.

Riemannian geometry is the branch of differential geometry that studies Riemannian manifolds, smooth manifolds with a Riemannian metric, i.e. with an inner product on the tangent space at each point that varies smoothly from point to point. This gives, in particular, local notions of angle, length of curves, surface area and volume. From those, some other global quantities can be derived by integrating local contributions.

In Riemannian geometry, an exponential map is a map from a subset of a tangent space TpM of a Riemannian manifold M to M itself. The (pseudo) Riemannian metric determines a canonical affine connection, and the exponential map of the (pseudo) Riemannian manifold is given by the exponential map of this connection.

In differential geometry, the Gaussian curvature or Gauss curvatureΚ of a surface at a point is the product of the principal curvatures, κ1 and κ2, at the given point:

In differential geometry, the Gauss map maps a surface in Euclidean space R3 to the unit sphere S2. Namely, given a surface X lying in R3, the Gauss map is a continuous map N: X → S2 such that N(p) is a unit vector orthogonal to X at p, namely the normal vector to X at p.

In mathematics, the Chern theorem states that the Euler-Poincaré characteristic of a closed even-dimensional Riemannian manifold is equal to the integral of a certain polynomial of its curvature form.

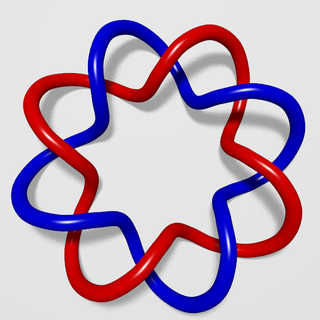

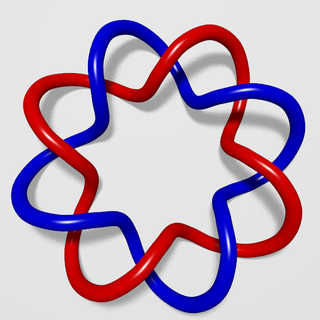

In mathematics, the linking number is a numerical invariant that describes the linking of two closed curves in three-dimensional space. Intuitively, the linking number represents the number of times that each curve winds around the other. The linking number is always an integer, but may be positive or negative depending on the orientation of the two curves.

In Riemannian geometry, the geodesic curvature of a curve measures how far the curve is from being a geodesic. For example, for 1D curves on a 2D surface embedded in 3D space, it is the curvature of the curve projected onto the surface's tangent plane. More generally, in a given manifold , the geodesic curvature is just the usual curvature of . However, when the curve is restricted to lie on a submanifold of , geodesic curvature refers to the curvature of in and it is different in general from the curvature of in the ambient manifold . The (ambient) curvature of depends on two factors: the curvature of the submanifold in the direction of , which depends only on the direction of the curve, and the curvature of seen in , which is a second order quantity. The relation between these is . In particular geodesics on have zero geodesic curvature, so that , which explains why they appear to be curved in ambient space whenever the submanifold is.

In the mathematical theory of knots, the Fáry–Milnor theorem, named after István Fáry and John Milnor, states that three-dimensional smooth curves with small total curvature must be unknotted. The theorem was proved independently by Fáry in 1949 and Milnor in 1950. It was later shown to follow from the existence of quadrisecants.

In mathematics, Hopf conjecture may refer to one of several conjectural statements from differential geometry and topology attributed to Heinz Hopf.

In mathematics, an immersion is a differentiable function between differentiable manifolds whose differential is everywhere injective. Explicitly, f : M → N is an immersion if

In mathematics, geometry and topology is an umbrella term for the historically distinct disciplines of geometry and topology, as general frameworks allow both disciplines to be manipulated uniformly, most visibly in local to global theorems in Riemannian geometry, and results like the Gauss–Bonnet theorem and Chern–Weil theory.

In mathematics, the differential geometry of surfaces deals with the differential geometry of smooth surfaces with various additional structures, most often, a Riemannian metric. Surfaces have been extensively studied from various perspectives: extrinsically, relating to their embedding in Euclidean space and intrinsically, reflecting their properties determined solely by the distance within the surface as measured along curves on the surface. One of the fundamental concepts investigated is the Gaussian curvature, first studied in depth by Carl Friedrich Gauss, who showed that curvature was an intrinsic property of a surface, independent of its isometric embedding in Euclidean space.

In mathematics, the Riemannian connection on a surface or Riemannian 2-manifold refers to several intrinsic geometric structures discovered by Tullio Levi-Civita, Élie Cartan and Hermann Weyl in the early part of the twentieth century: parallel transport, covariant derivative and connection form. These concepts were put in their current form with principal bundles only in the 1950s. The classical nineteenth century approach to the differential geometry of surfaces, due in large part to Carl Friedrich Gauss, has been reworked in this modern framework, which provides the natural setting for the classical theory of the moving frame as well as the Riemannian geometry of higher-dimensional Riemannian manifolds. This account is intended as an introduction to the theory of connections.

In differential geometry, the total absolute curvature of a smooth curve is a number defined by integrating the absolute value of the curvature around the curve. It is a dimensionless quantity that is invariant under similarity transformations of the curve, and that can be used to measure how far the curve is from being a convex curve.