Related Research Articles

Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337. He was the first emperor to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterranea, he was the son of Flavius Constantius, a Roman army officer of Illyrian origin who had been one of the four rulers of the Tetrarchy. His mother, Helena, was a Greek woman of low birth and a Christian. Later canonized as a saint, she is traditionally attributed with the conversion of her son. Constantine served with distinction under the Roman emperors Diocletian and Galerius. He began his career by campaigning in the eastern provinces before being recalled in the west to fight alongside his father in the province of Britannia. After his father's death in 306, Constantine was acclaimed as augustus (emperor) by his army at Eboracum. He eventually emerged victorious in the civil wars against emperors Maxentius and Licinius to become the sole ruler of the Roman Empire by 324.

Theodosius I, also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two civil wars, and was instrumental in establishing the creed of Nicaea as the orthodox doctrine for Christianity. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule the entire Roman Empire before its administration was permanently split between the West and East.

Tertullian was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of Latin Christian literature. He was an early Christian apologist and a polemicist against heresy, including contemporary Christian Gnosticism. Tertullian has been called "the father of Latin Christianity", as well as "the founder of Western theology".

Year 475 (CDLXXV) was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Zeno without colleague. The denomination 475 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Gratian was emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 367 to 383. The eldest son of Valentinian I, Gratian was raised to the rank of Augustus as a child and inherited the West after his father's death in 375. He nominally shared the government with his infant half-brother Valentinian II, who was also acclaimed emperor in Pannonia on Valentinian's death. The East was ruled by his uncle Valens, who was later succeeded by Theodosius I.

Demetrius III Theos Philopator Soter Philometor Euergetes Callinicus was a Hellenistic Seleucid monarch who reigned as the King of Syria between 96 and 87 BC. He was a son of Antiochus VIII and, most likely, his Egyptian wife Tryphaena. Demetrius III's early life was spent in a period of civil war between his father and his uncle Antiochus IX, which ended with the assassination of Antiochus VIII in 96 BC. After the death of their father, Demetrius III took control of Damascus while his brother Seleucus VI prepared for war against Antiochus IX, who occupied the Syrian capital Antioch.

Philip I, commonly known as Philip the Arab was Roman emperor from 244 to 249. He was born in Aurantis, Arabia, in a city situated in modern-day Syria. After the death of Gordian III in February 244, Philip, who had been Praetorian prefect, achieved power. He quickly negotiated peace with the Persian Sassanid Empire and returned to Rome to be confirmed by the Senate. During his reign, the city of Rome celebrated its millennium.

Antiochus XII Dionysus Epiphanes Philopator Callinicus was a Hellenistic Seleucid monarch who reigned as King of Syria between 87 and 82 BC. The youngest son of Antiochus VIII and, most likely, his Egyptian wife Tryphaena, Antiochus XII lived during a period of civil war between his father and his uncle Antiochus IX, which ended with the assassination of Antiochus VIII in 96 BC. Antiochus XII's four brothers laid claim to the throne, eliminated Antiochus IX as a claimant, and waged war against his heir Antiochus X.

The Ghassanids (Arabic: الغساسنة, romanized: al-Ġasāsina, also Banu Ghassān, also called the Jafnids, were an Arab tribe which founded a kingdom. They emigrated from South Arabia in the early third century to the Levant. Some merged with Hellenized Christian communities, converting to Christianity in the first few centuries, while others may have already been Christians before emigrating north to escape religious persecution.

Al-Samawʾal ibn Yaḥyā al-Maghribī, commonly known as Samau'al al-Maghribi, was a mathematician, astronomer and physician. Born to a Jewish family, he concealed his conversion to Islam for many years in fear of offending his father, then openly embraced Islam in 1163 after he had a dream telling him to do so. His father was a Rabbi from Morocco.

Dame Averil Millicent Cameron, often cited as A. M. Cameron, is a British historian. She writes on Late Antiquity, Classics, and Byzantine Studies. She was Professor of Late Antique and Byzantine History at the University of Oxford, and the Warden of Keble College, Oxford, between 1994 and 2010.

The growth of Christianity from its obscure origin c. 40 AD, with fewer than 1,000 followers, to being the majority religion of the entire Roman Empire by AD 350, has been examined through a wide variety of historiographical approaches.

The Melitians, sometimes called the Church of the Martyrs, were an early Christian sect in Egypt. They were founded about 306 by Bishop Melitius of Lycopolis and survived as a small group into the eighth century. The point on which they broke with the larger Catholic church was the same as that of the contemporary Donatists in the province of Africa: the ease with which lapsed Christians were received back into communion. The resultant division in the church of Egypt is known as the Melitian schism.

Christian mission to Jews, evangelism among Jews, or proselytism to Jews, is a subset of Christian missionary activities which are engaged in for the specific purpose of converting Jews to Christianity.

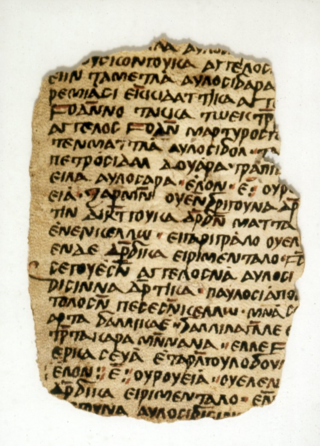

The Dialogue of Jason and Papiscus is a lost early Christian text in Greek describing the dialogue of a converted Jew, Jason, and an Alexandrian Jew, Papiscus. The text is first mentioned, critically, in the True Account of the anti-Christian writer Celsus, and therefore would have been contemporary with the surviving, and much more famous, Dialogue between the convert from paganism Justin Martyr and Trypho the Jew.

Amulo Lugdunensis served as Archbishop of Lyon from 841 to 852 AD. As a Gallic prelate, Amulo is best known for his letters concerning two major themes: Christian–Jewish relations in the Frankish kingdom and the Carolingian controversy over predestination. He was ordained as archbishop in January 841.

Pseudo-Chrysostom is the designation used for the anonymous authors of texts falsely or erroneously attributed to John Chrysostom. Most such works are sermons, since a large number of John's actual sermons survive.

John the Stylite, also known as John of Litharb, was a Syriac Orthodox monk and author. He was a stylite attached to the monastery of Atarib and part of a circle of Syriac intellectuals active in northern Syria under the Umayyad dynasty.

In the Byzantine Empire, cities were centers of economic and cultural life. A significant part of the cities were founded during the period of Greek and Roman antiquity. The largest of them were Constantinople, Alexandria and Antioch, with a population of several hundred thousand people. Large provincial centers had a population of up to 50,000. Although the spread of Christianity negatively affected urban institutions, in general, late antique cities continued to develop continuously. Byzantium remained an empire of cities, although the urban space had changed a lot. If the Greco-Roman city was a place of pagan worship and sports events, theatrical performances and chariot races, the residence of officials and judges, then the Byzantine city was primarily a religious center where the bishop's residence was located.

The Apocalypse of John Chrysostom, also called the Second Apocryphal Apocalypse of John, is a Christian text composed in Greek between the 6th and 8th centuries AD. Although the text is often called an apocalypse by analogy with the similarly structured First Apocryphal Apocalypse of John, the text is not a true apocalypse. In the manuscripts, it is called "a word of teaching" or "a treatise". It is usually classified as part of the New Testament apocrypha because it describes an apocryphal encounter between John of Patmos and Jesus. In a number of manuscripts, it is presented as a sermon of John Chrysostom, who, rather than the apostle, is Jesus's interlocutor.

References

- ↑ Adversus Judaeous by Arthur Lukyn Williams

- ↑ Nuffelen, Peter Van. "2017. Prepared for All Occasions: The Trophies of Damascus and the Bonwetsch Dialogue, in A. Cameron and N. Gaul, eds., Dialogues and Debates from Late Antiquity to Late Byzantium, Routledge, London, 2017, 65-76".

- ↑ Nuffelen, Peter Van. "2017. Prepared for All Occasions: The Trophies of Damascus and the Bonwetsch Dialogue, in A. Cameron and N. Gaul, eds., Dialogues and Debates from Late Antiquity to Late Byzantium, Routledge, London, 2017, 65-76".

- ↑ Nuffelen, Peter Van. "2017. Prepared for All Occasions: The Trophies of Damascus and the Bonwetsch Dialogue, in A. Cameron and N. Gaul, eds., Dialogues and Debates from Late Antiquity to Late Byzantium, Routledge, London, 2017, 65-76".

- ↑ Adversus Judaeous by Arthur Lukyn Williams

- ↑ Adversus Judaeous by Arthur Lukyn Williams

- ↑ Adversus Judaeous by Arthur Lukyn Williams

- ↑ Adversus Judaeous by Arthur Lukyn Williams

- ↑ Nuffelen, Peter Van. "2017. Prepared for All Occasions: The Trophies of Damascus and the Bonwetsch Dialogue, in A. Cameron and N. Gaul, eds., Dialogues and Debates from Late Antiquity to Late Byzantium, Routledge, London, 2017, 65-76".

- ↑ Nuffelen, Peter Van. "2017. Prepared for All Occasions: The Trophies of Damascus and the Bonwetsch Dialogue, in A. Cameron and N. Gaul, eds., Dialogues and Debates from Late Antiquity to Late Byzantium, Routledge, London, 2017, 65-76".

- ↑ Nuffelen, Peter Van. "2017. Prepared for All Occasions: The Trophies of Damascus and the Bonwetsch Dialogue, in A. Cameron and N. Gaul, eds., Dialogues and Debates from Late Antiquity to Late Byzantium, Routledge, London, 2017, 65-76".

- ↑ Nuffelen, Peter Van. "2017. Prepared for All Occasions: The Trophies of Damascus and the Bonwetsch Dialogue, in A. Cameron and N. Gaul, eds., Dialogues and Debates from Late Antiquity to Late Byzantium, Routledge, London, 2017, 65-76".

- ↑ Adversus Judaeous by Arthur Lukyn Williams