Related Research Articles

A polygraph, often incorrectly referred to as a lie detector test, is a junk science device or procedure that measures and records several physiological indicators such as blood pressure, pulse, respiration, and skin conductivity while a person is asked and answers a series of questions. The belief underpinning the use of the polygraph is that deceptive answers will produce physiological responses that can be differentiated from those associated with non-deceptive answers; however, there are no specific physiological reactions associated with lying, making it difficult to identify factors that separate those who are lying from those who are telling the truth.

Deception is an act or statement that misleads, hides the truth, or promotes a belief, concept, or idea that is not true. This occurs when a deceiver uses information against a person to make them believe an idea is true. Deception can be used with both verbal and nonverbal messages. The person creating the deception knows it to be false while the receiver of the message has a tendency to believe it. It is often done for personal gain or advantage. Deception can involve dissimulation, propaganda and sleight of hand as well as distraction, camouflage or concealment. There is also self-deception, as in bad faith. It can also be called, with varying subjective implications, beguilement, deceit, bluff, mystification, ruse, or subterfuge.

A lie is an assertion that is believed to be false, typically used with the purpose of deceiving or misleading someone. The practice of communicating lies is called lying. A person who communicates a lie may be termed a liar. Lies can be interpreted as deliberately false statements or misleading statements, though not all statements that are literally false are considered lies – metaphors, hyperboles, and other figurative rhetoric are not intended to mislead, while lies are explicitly meant for literal interpretation by their audience. Lies may also serve a variety of instrumental, interpersonal, or psychological functions for the individuals who use them.

Honesty or truthfulness is a facet of moral character that connotes positive and virtuous attributes such as integrity, truthfulness, straightforwardness, along with the absence of lying, cheating, theft, etc. Honesty also involves being trustworthy, loyal, fair, and sincere.

Self-deception is a process of denying or rationalizing away the relevance, significance, or importance of opposing evidence and logical argument. Self-deception involves convincing oneself of a truth so that one does not reveal any self-knowledge of the deception.

A microexpression is a facial expression that only lasts for a short moment. It is the innate result of a voluntary and an involuntary emotional response occurring simultaneously and conflicting with one another, and occurs when the amygdala responds appropriately to the stimuli that the individual experiences and the individual wishes to conceal this specific emotion. This results in the individual very briefly displaying their true emotions followed by a false emotional reaction.

Lie detection is an assessment of a verbal statement with the goal to reveal a possible intentional deceit. Lie detection may refer to a cognitive process of detecting deception by evaluating message content as well as non-verbal cues. It also may refer to questioning techniques used along with technology that record physiological functions to ascertain truth and falsehood in response. The latter is commonly used by law enforcement in the United States, but rarely in other countries because it is based on pseudoscience.

Interpersonal deception theory (IDT) is one of a number of theories that attempts to explain how individuals handle actual deception at the conscious or subconscious level while engaged in face-to-face communication. The theory was put forth by David Buller and Judee Burgoon in 1996 to explore this idea that deception is an engaging process between receiver and deceiver. IDT assumes that communication is not static; it is influenced by personal goals and the meaning of the interaction as it unfolds. IDT is no different from other forms of communication since all forms of communication are adaptive in nature. The sender's overt communications are affected by the overt and covert communications of the receiver, and vice versa. IDT explores the interrelation between the sender's communicative meaning and the receiver's thoughts and behavior in deceptive exchanges.

Information Manipulation Theory (IMT) & is a theory of deceptive discourse production, rooted in H. Paul Grice's theory of conversational implicature. IMT argues that, rather than communicators producing "truths" and "lies," the vast majority of everyday deceptive discourse involves complicated combinations of elements that fall somewhere in between these polar opposites; with the most common form of deception being the editing-out of contextually problematic information. More specifically, individuals have available to them four different ways of misleading others: playing with the amount of relevant information that is shared, including false information, presenting irrelevant information, and/or presenting information in an overly vague fashion. As long as such manipulations remain covert - that is, undetected by recipients - deception will succeed. Two of the most important practical implications of IMT are that deceivers commonly use messages that are composed entirely of truthful information to deceive; and that because this is the case, our ability to detect deception in real-world environments is extremely limited.

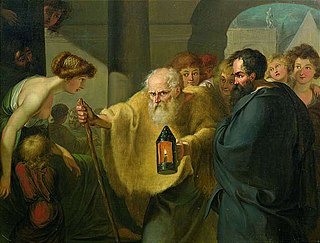

The Wizards Project was a research project at the University of California, San Francisco led by Paul Ekman and Maureen O'Sullivan that studied the ability of people to detect lies. The experts identified in their study were called "Truth Wizards". O'Sullivan spent more than 20 years studying the science of lying and deceit. The project was originally named the Diogenes Project, after Diogenes of Sinope, the Greek philosopher who would look into people's faces using a lamp, claiming to be looking for an honest man.

Relational transgressions occur when people violate implicit or explicit relational rules. These transgressions include a wide variety of behaviors. The boundaries of relational transgressions are permeable. Betrayal for example, is often used as a synonym for a relational transgression. In some instances, betrayal can be defined as a rule violation that is traumatic to a relationship, and in other instances as destructive conflict or reference to infidelity.

Non-verbal leakage is a form of non-verbal behavior that occurs when a person verbalizes one thing, but their body language indicates another, common forms of which include facial movements and hand-to-face gestures. The term "non-verbal leakage" got its origin in literature in 1968, leading to many subsequent studies on the topic throughout the 1970s, with related studies continuing today.

The Silent Talker Lie Detector is an attempt to increase the accuracy of the most common lie detector, the polygraph, which does not directly measure whether the subject is truthful, but records physiological measures that are associated with emotional responses. The Silent Talker gives the evaluator access to viewing microexpressions by adding a camera to the process. The creators claim that microexpressions are actual indicators of lying, while many other things could cause an emotional response. Since microexpressions are fleeting, the camera allows the examiner to capture data that otherwise would have been missed. However, the scientific community is not convinced that this system accomplishes what it claims and some call it pseudoscience.

Othello error occurs when a suspicious observer discounts cues of truthfulness. Essentially the Othello error occurs, Paul Ekman states, "when the lie catcher fails to consider that a truthful person who is under stress may appear to be lying," their non-verbal signals expressing their worry at the possibility of being disbelieved. A lie-detector or polygraph may be deceived in the same way by misinterpreting nervous signals from a truthful person. The error is named after William Shakespeare's tragic play Othello; the dynamics between the two main characters, Othello and Desdemona, are a particularly well-known example of the error in practice.

Mark G. Frank is a communication professor and department chair, and an internationally recognized expert on human nonverbal communication, emotion, and deception. He conducts research and does training on micro expressions of emotion and of the face. His research studies include other nonverbal indicators of deception throughout the rest of the body. He is the Director of the Communication Science Center research laboratory that is located on the North Campus of the University at Buffalo. Under his guidance, a team of graduate researchers conduct experiments and studies for private and government entities. Frank uses his expertise in communication and psychology to assist law enforcement agencies in monitoring both verbal and nonverbal communication.

Timothy R. Levine is an American communication professor, prolific researcher, and theorist. He is Distinguished Professor and Chair of Communication Studies at University of Alabama at Birmingham. Levine is credited as one of the most central and prolific researchers in the field of Communication Studies, is known for his work as the creator of truth-default theory, his developmental work on the veracity effect, and editing of the encyclopedia of deception. He is the author of Duped, published by The University of Alabama Press.

David M. Markowitz is a communication professor at the University of Oregon who specializes in the study of language and deception. Much of his work focuses on how technological channels impact the encoding and decoding of messages. His work has captured the attention of magazines and outlets in popular culture; he writes articles for Forbes magazine about deception. Much of his research has utilized analyses of linguistic and analytic styles of writing, for example, Markowitz's work on pet adoption ads was referenced in a website featuring tips on how to write better pet adoption ads.

fMRI lie detection is a field of lie detection using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). FMRI looks to the central nervous system to compare time and topography of activity in the brain for lie detection. While a polygraph detects anxiety-induced changes in activity in the peripheral nervous system, fMRI purportedly measures blood flow to areas of the brain involved in deception.

Motivation impairment effect (MIE) is a hypothesised behavioral effect relating to the communication of deception. The MIE posits that people who are highly motivated to deceive are less successful in their goal when their speech and mannerisms are observed by the intended audience. This is because their nonverbal cues, such as adaptor gestures, sweating, kinesic behaviors, verbal disfluencies, etc, tend to be more pronounced due to increased stress, cognitive load, and heightened emotional state. There is some disagreement regarding the MIE hypothesis, with a few nonverbal communication scholars arguing that deception should not be examined as separate for senders and receivers, but rather as an integral part of the overall process.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Levine, Timothy R. (2014-05-23). "Truth-Default Theory (TDT)". Journal of Language and Social Psychology . 33 (4): 378–392. doi:10.1177/0261927x14535916. ISSN 0261-927X. S2CID 146916525.

- ↑ "Deception". Timothy R. Levine. Retrieved 2018-10-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Levine, Timothy (2014). "Truth-Default Theory (TDT): A Theory of Human Deception and Deception Detection". Journal of Language and Social Psychology . 33: 378–392. doi:10.1177/0261927X14535916. S2CID 146916525.

- ↑ Buller, D. B.; Burgoon, J. K. (1996). "Interpersonal Deception Theory". Communication Theory . 6 (3): 203–242. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.1996.tb00127.x. S2CID 146464264.

- ↑ Levine, Timothy R.; Kim, Rachel K.; Hamel, Lauren M. (2010-11-04). "People Lie for a Reason: Three Experiments Documenting the Principle of Veracity". Communication Research Reports . 27 (4): 271–285. doi:10.1080/08824096.2010.496334. ISSN 0882-4096. S2CID 36429576.

- ↑ Daly, John A.; Wiemann, John M. (2013-01-11). Strategic Interpersonal Communication. Routledge. ISBN 9781136563751.

- ↑ McCornack, Steven; Parks, Malcolm (1986). "Deception Detection and Relationship Development: The Other Side of Trust". Annals of the International Communication Association . 9: 377–389. doi:10.1080/23808985.1986.11678616.

- 1 2 3 4 Levine, Timothy R. "Deception Research at Michigan State University". msu.edu.

- ↑ McCornack, Steven A.; Parks, Malcolm R. (1986-01-01). "Deception Detection and Relationship Development: The Other Side of Trust". Annals of the International Communication Association . 9 (1): 377–389. doi:10.1080/23808985.1986.11678616. ISSN 2380-8985.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Miron; DePaulo, Bella M.; Rosenthal, Robert (1981), "Verbal and Nonverbal Communication of Deception", Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Elsevier, vol. 14, pp. 1–59, doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60369-x, ISBN 978-0-12-015214-8 , retrieved 2022-05-31

- 1 2 Levine, Timothy; Hee, Park; McCornack, Steven (1999). "Accuracy in detecting truths and lies: Documenting the "veracity effect"". Communication Monographs . 66 (2): 125–144. doi:10.1080/03637759909376468.

- ↑ Vrij, A., & Baxter, M. (1999). Accuracy and confidence in detecting truths andlies in elaborations and denials: Truth bias, lie bias and individual differences. Expert evidence, 7(1), 25-36.

- 1 2 Masip, Jaume; Garrido, Eugenio; Herrero, Carmen (2009). "Heuristic versus Systematic Processing of Information in Detecting Deception: Questioning the Truth Bias". Psychological Reports. 105 (1): 11–36. doi:10.2466/PR0.105.1.11-36. PMID 19810430. S2CID 34448167.

- ↑ Levine, Timothy R.; Anders, Lori N.; Banas, John; Baum, Karie Leigh; Endo, Keriane; Hu, Allison D. S.; Wong, Norman C. H. (February 28, 2000). "Norms, expectations, and deception: A norm violation model of veracity judgments". Communication Monographs . 67 (2): 123–137. doi:10.1080/03637750009376500. ISSN 0363-7751. S2CID 144416761.

- 1 2 Levine, Timothy R.; Park, Hee Sun; McCornack, Steven A. (June 1999). "Accuracy in detecting truths and lies: Documenting the "veracity effect"". Communication Monographs . 66 (2): 125–144. doi:10.1080/03637759909376468. ISSN 0363-7751.

- ↑ "Deception". Timothy R. Levine. Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- ↑ Levine, Timothy R.; McCornack, Steven A. (June 1996). "A Critical Analysis of the Behavioral Adaptation Explanation of the Probing Effect". Human Communication Research . 22 (4): 575–588. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1996.tb00380.x. ISSN 0360-3989.

- ↑ Street, C. N. H. (2015). "ALIED: Humans as adaptive lie detectors" (PDF). Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition . 4 (4): 335–343. doi:10.1016/j.jarmac.2015.06.002.

- 1 2 DePaulo, B.; Lindsay, J. J; Malone, B. E.; Muhlenbruck, L.; Charlton, K.; Cooper, H. (2003). "Cues to deception". Psychological Bulletin. 129 (1): 74–118. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.74. PMID 12555795.

- ↑ DePaulo, B.; Kashy, D. A.; Kirkendol, S. E.; Wyer, M. M.; Epstein, J. A. (1996). "Lying in everyday life". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . 70 (5): 979–995. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.979. PMID 8656340.

- ↑ Bond, G. D.; Malloy, D. M.; Arias, E. A.; Nunn, S. N.; Thompson, L. A. (2005). "Lie-biased decision making in prison". Communication Reports. 18 (1–2): 9–19. doi:10.1080/08934210500084180. S2CID 144692545.

- ↑ DePaulo, P. J.; DePaulo, B. M. (1989). "Can deception by salespersons and customers be detected through nonverbal behavioural cues?". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 19 (18): 1552–1577. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1989.tb01463.x.

- ↑ Masip, Jaume; Alonso, Hernán; Garrido, Eugenio; Herrero, Carmen (2009). "Training to detect what? The biasing effects of training on veracity judgments". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 23 (9): 1282–1296. doi:10.1002/acp.1535.

- ↑ Levine, Timothy (2011). "Sender Demeanor: Individual Differences in Sender Believability Have a Powerful Impact on Deception Detection Judgments" (PDF). Squarspace.

- 1 2 3 Verschuere, Bruno; Shalvi, Shaul (2014-05-19). "The Truth Comes Naturally! Does It?". Journal of Language and Social Psychology . 33 (4): 417–423. doi:10.1177/0261927x14535394. hdl: 1854/LU-5772963 . ISSN 0261-927X. S2CID 147101193.