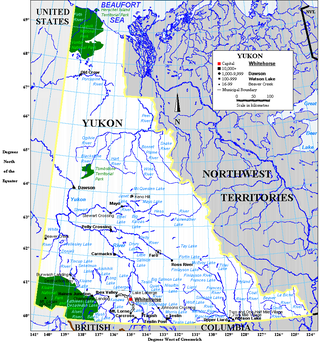

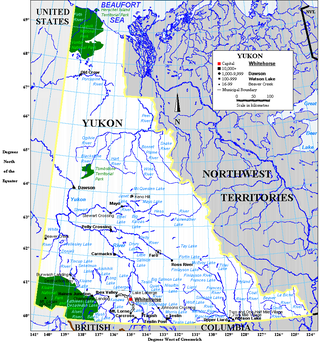

Yukon is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 44,975 as of 2023. However, Whitehorse, the territorial capital, is the largest settlement in any of the three territories.

Tanacross is an endangered Athabaskan language spoken by fewer than 60 people in eastern Interior Alaska.

The Hän language is a Northern Athabaskan language spoken by the Hän Hwëch'in. Athabascan refers to the interrelated complexity of languages spoken in Canada and Alaska each with its own dialect: the village of Eagle, Alaska in the United States and the town of Dawson City, Yukon Territory in Canada, though there are also Hän speakers in the nearby city of Fairbanks, Alaska. Furthermore, there was a decline in speakers in Dawson City as a result of the influx of gold miners in the mid-19th century.

The Gwichʼin language belongs to the Athabaskan language family and is spoken by the Gwich'in First Nation (Canada) / Alaska Native People. It is also known in older or dialect-specific publications as Kutchin, Takudh, Tukudh, or Loucheux. Gwich'in is spoken primarily in the towns of Inuvik, Aklavik, Fort McPherson, and Tsiigehtchic, all in the Northwest Territories and Old Crow in Yukon of Canada. In Alaska of the United States, Gwichʼin is spoken in Beaver, Circle, Fort Yukon, Chalkyitsik, Birch Creek, Arctic Village, Eagle, and Venetie.

ǂʼAmkoeAM-koy, formerly called by the dialectal name ǂHoan, is a severely endangered Kxʼa language of Botswana. West ǂʼAmkoe dialect, along with Taa and Gǀui, form the core of the Kalahari Basin sprachbund, and share a number of characteristic features, including the largest consonant inventories in the world. ǂʼAmkoe was shown to be related to the Juu languages by Honken and Heine (2010), and these have since been classified together in the Kxʼa language family.

The Muscogee language, also known as Creek, is a Muskogean language spoken by Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole people, primarily in the US states of Oklahoma and Florida. Along with Mikasuki, when it is spoken by the Seminole, it is known as Seminole.

Tatshenshini-Alsek Park or Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Wilderness Park is a provincial park in British Columbia, Canada 9,580 km2 (3,700 sq mi). It was established in 1993 after an intensive campaign by Canadian and American conservation organizations to halt mining exploration and development in the area, and protect the area for its strong natural heritage and biodiversity values.

The Champagne and Aishihik First Nations (CAFN) is a First Nation band government in Yukon, Canada. Historically its original population centres were Champagne and Aishihik, with bands active in both coastal and interior areas.

The Kluane First Nation (KFN) is a First Nations band government in Yukon, Canada. Its main centre is in Burwash Landing, Yukon along the Alaska Highway on the shores of Kluane Lake, the territory's largest lake. The native language spoken by the people of this First Nation is Southern Tutchone. They call themselves after the great Lake Lù’àn Män Ku Dän or Lù’àn Mun Ku Dän.

The White River First Nation (WRFN) is a First Nation of Upper Tanana, Northern Tutchone, and Southern Tutchone peoples in the western Yukon Territory in Canada. Its main population centre is Beaver Creek, Yukon.

Tagish was a language spoken by the Tagish or Carcross-Tagish, a First Nations people that historically lived in the Northwest Territories and Yukon in Canada. The name Tagish derives from /ta:gizi dene/, or "Tagish people", which is how they refer to themselves, where /ta:gizi/ is a place name meaning "it is breaking up.

The Southern Tutchone are a First Nations people of the Athabaskan-speaking ethnolinguistic group living mainly in the southern Yukon in Canada. The Southern Tutchone language, traditionally spoken by the Southern Tutchone people, is a variety of the Tutchone language, part of the Athabaskan language family. Some linguists suggest that Northern and Southern Tutchone are distinct and separate languages.

The Tolowa language is a member of the Pacific Coast subgroup of the Athabaskan language family. Together with three other closely related languages it forms a distinctive Oregon Athabaskan cluster within the subgroup.

Omaha–Ponca is a Siouan language spoken by the Omaha (Umoⁿhoⁿ) people of Nebraska and the Ponca (Paⁿka) people of Oklahoma and Nebraska. The two dialects differ minimally but are considered distinct languages by their speakers.

Pu–Xian Min, also known as Putian–Xianyou Min, Puxian Min, Pu–Xian Chinese, Xinghua, Henghwa or Hinghwa, is a Sinitic language that forms a branch of Min Chinese. Pu-Xian is a transitional variety of Coastal Min which shares characteristics with both Eastern Min and Southern Min, although it is closer to the latter.

Kusawa Lake is a lake in the southern Yukon, Canada. Kusawa means "long narrow lake" in the Tlingit language. The Kusawa Lake is a lake in Canada's Yukon Territory. It is located at an altitude of 671 m (2,201 ft) and is 60 km (37 mi) southwest of Whitehorse near the British Columbia border. It meanders over a length of 75 km (47 mi) with a maximum width of about 2.5 km (1.6 mi) through the mountains in the north of the Boundary Ranges. It is fed by the Primrose River and Kusawa River. The Takhini outflows to the Yukon River from the northern tip of Kusawa Lake. Kusawa Lake has an area of 142 km2 (55 sq mi). The lake has a maximum depth of 140 m (460 ft) and is of glacial origin. It is a common tourist destination and is also popular for fishing.

Southern Athabaskan is a subfamily of Athabaskan languages spoken primarily in the Southwestern United States with two outliers in Oklahoma and Texas. The languages are spoken in the northern Mexican states of Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila and to a much lesser degree in Durango and Nuevo León. Those languages are spoken by various groups of Apache and Navajo peoples. Elsewhere, Athabaskan is spoken by many indigenous groups of peoples in Alaska, Canada, Oregon and northern California.

Louise Profeit-LeBlanc is an Aboriginal storyteller, cultural educator artist, writer, choreographer, and film script writer from the Northern Tutchone Nation, Athabaskan language spoken in northeastern Yukon in Canada. She was raised in Mayo.

The Indigenous peoples of Yukon are ethnic groups who, prior to European contact, occupied the former countries now collectively known as Yukon. While most First Nations in the Canadian territory are a part of the wider Dene Nation, there are Tlingit and Métis nations that blend into the wider spectrum of indigeneity across Canada. Traditionally hunter-gatherers, indigenous peoples and their associated nations retain close connections to the land, the rivers and the seasons of their respective countries or homelands. Their histories are recorded and passed down the generations through oral traditions. European contact and invasion brought many changes to the native cultures of Yukon including land loss and non-traditional governance and education. However, indigenous people in Yukon continue to foster their connections with the land in seasonal wage labour such as fishing and trapping. Today, indigenous groups aim to maintain and develop indigenous languages, traditional or culturally-appropriate forms of education, cultures, spiritualities and indigenous rights.

The Yukon Ice Patches are a series of dozens of ice patches in the southern Yukon discovered in 1997, which have preserved hundreds of archaeological artifacts, with some more than 9,000 years old. The first ice patch was discovered on the mountain Thandlät, west of the Kusawa Lake campground which is 60 km (37 mi) west of Whitehorse, Yukon. The Yukon Ice Patch Project began shortly afterwards with a partnership between archaeologists in partnership with six Yukon First Nations, on whose traditional territory the ice patches were found. They include the Carcross/Tagish First Nation, the Kwanlin Dün First Nation, the Ta’an Kwäch’än Council, the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, the Kluane First Nation, and the Teslin Tlingit Council.